Page

Last Updated:

Wednesday, 04 November 2015 13:35 EDT, © 1964, 2007, 2008, 2010,

2011, 2012, 2013

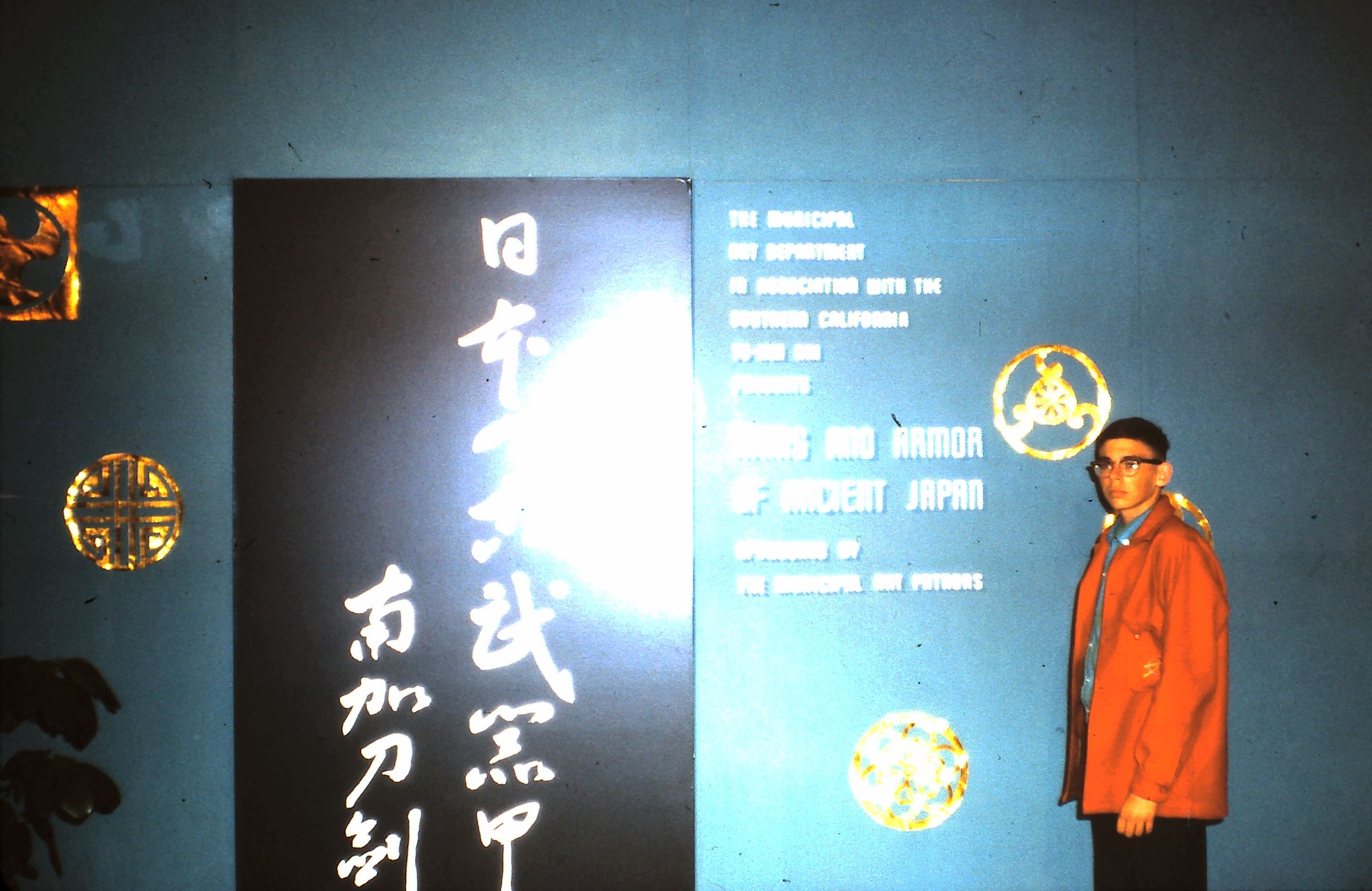

ARMS AND ARMOR OF ANCIENT JAPAN

An Historical Survey

Dean S. Hartley, Jr., President Nanka Token Kai

Fred Martin and Bob Haynes, Exhibition Co-Chairmen

Co-Sponsored

by the

Municipal Art Patrons of Los Angeles

and the

Southern California To-Ken Kai

Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Park

February 19th Through March 22nd, 1964

|

Grand Opening: Two unidentified women,

Mayor Sam Yorty, Mrs. D. S. Hartley, Jr. |

|

Dean Hartley |

Fred Martin |

Bob Haynes |

|

Hartley & Japanese Consul General (Los Angeles) |

Opening Banner |

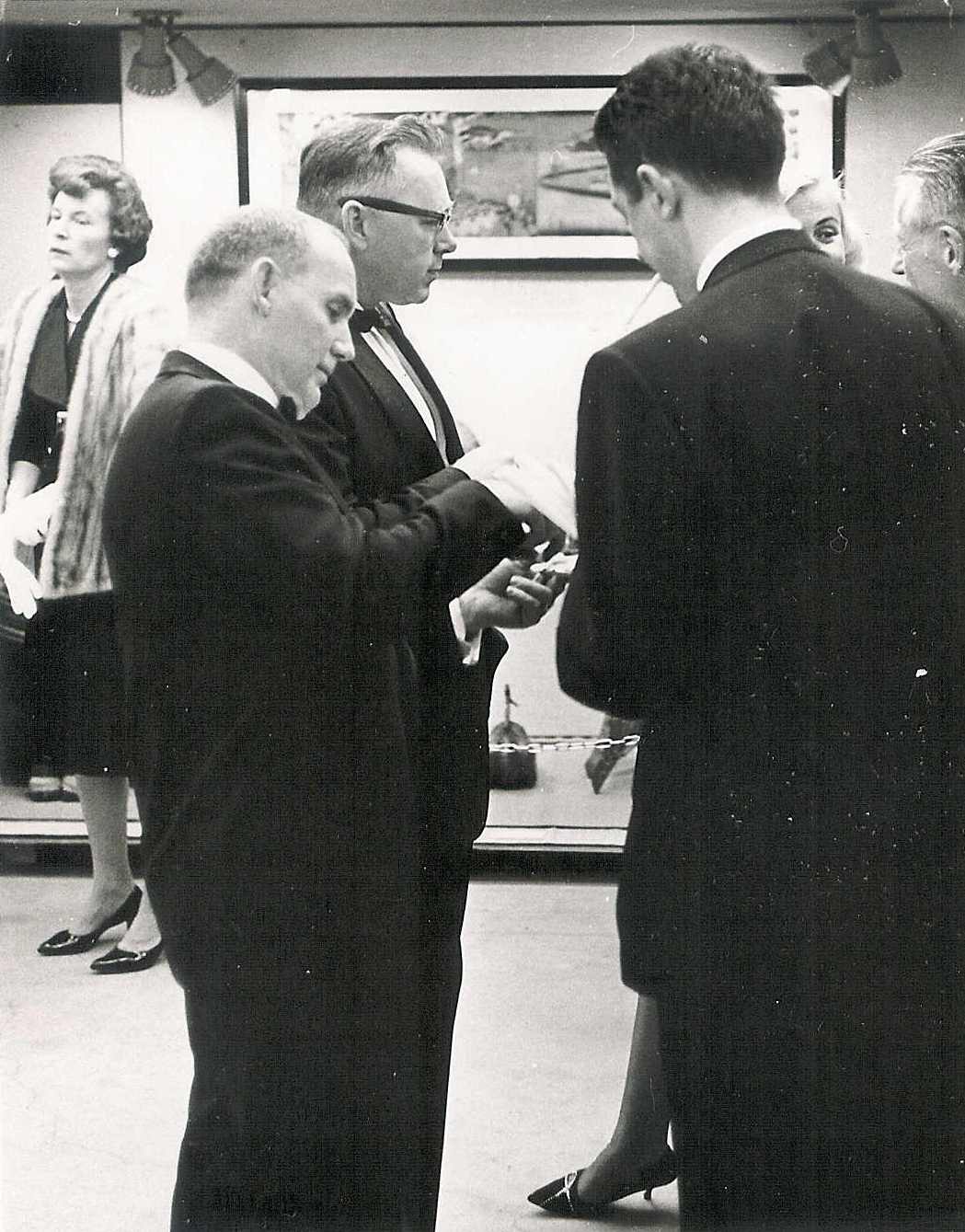

Willis Hawley & Hartley |

|

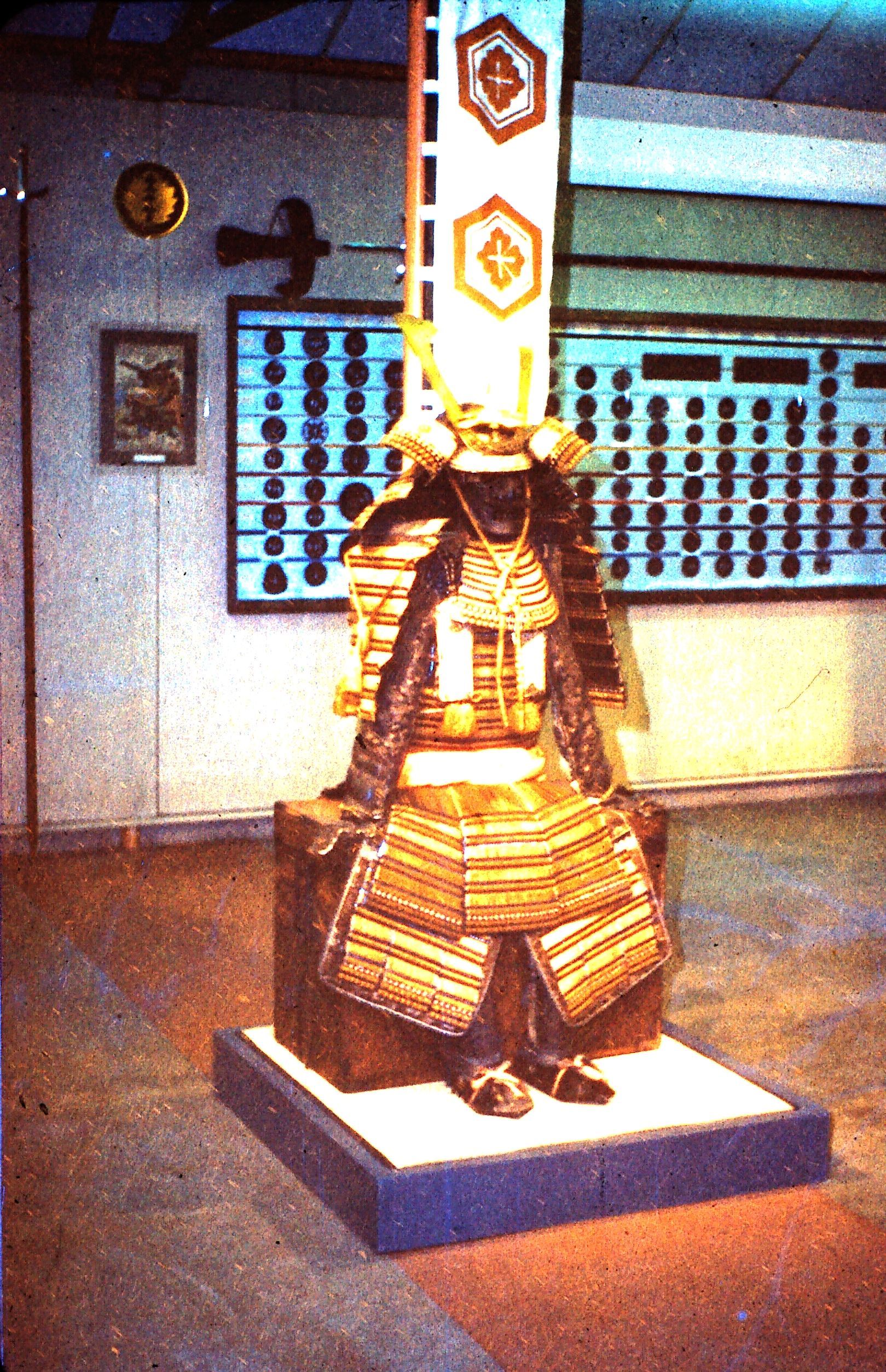

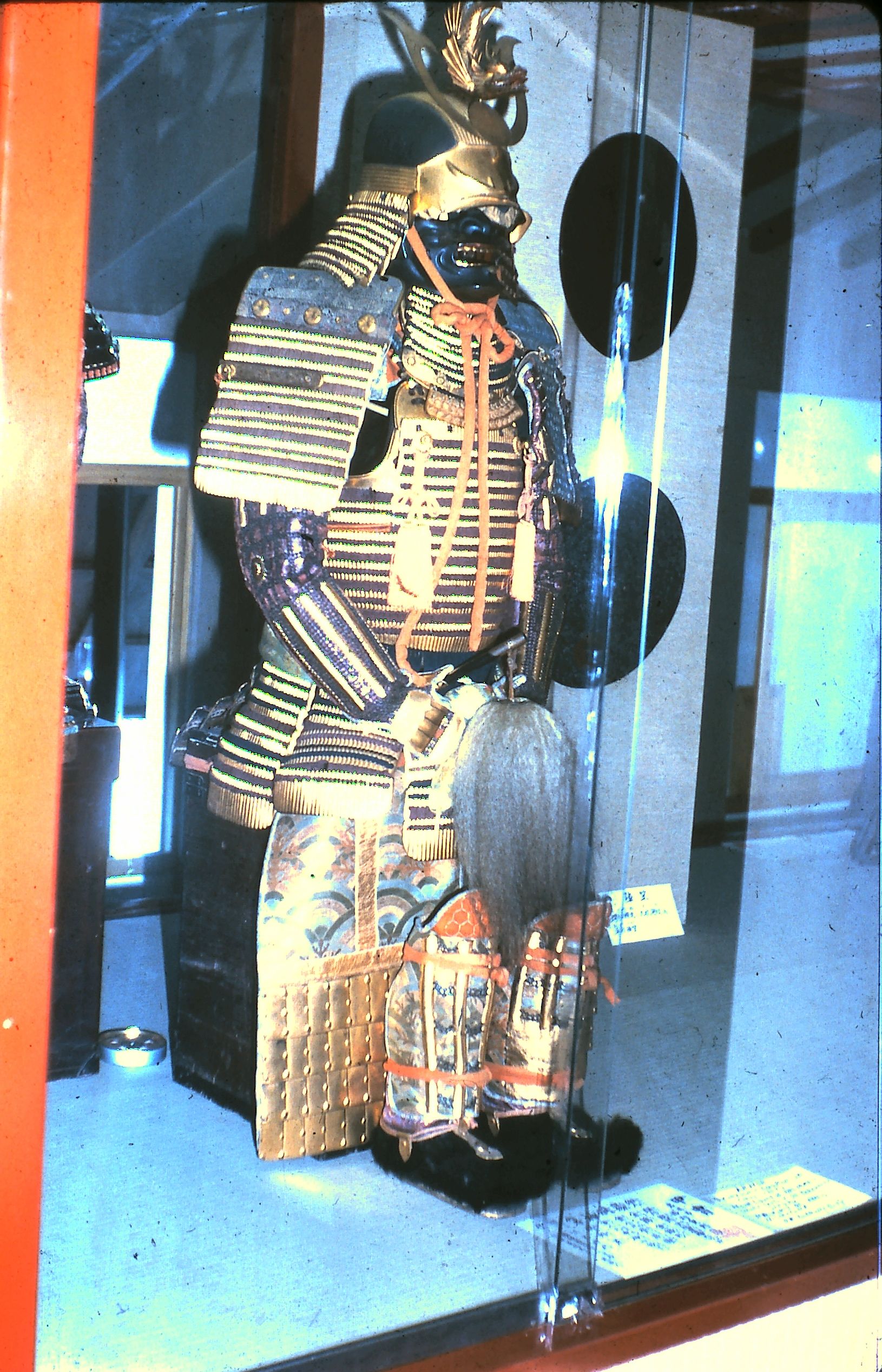

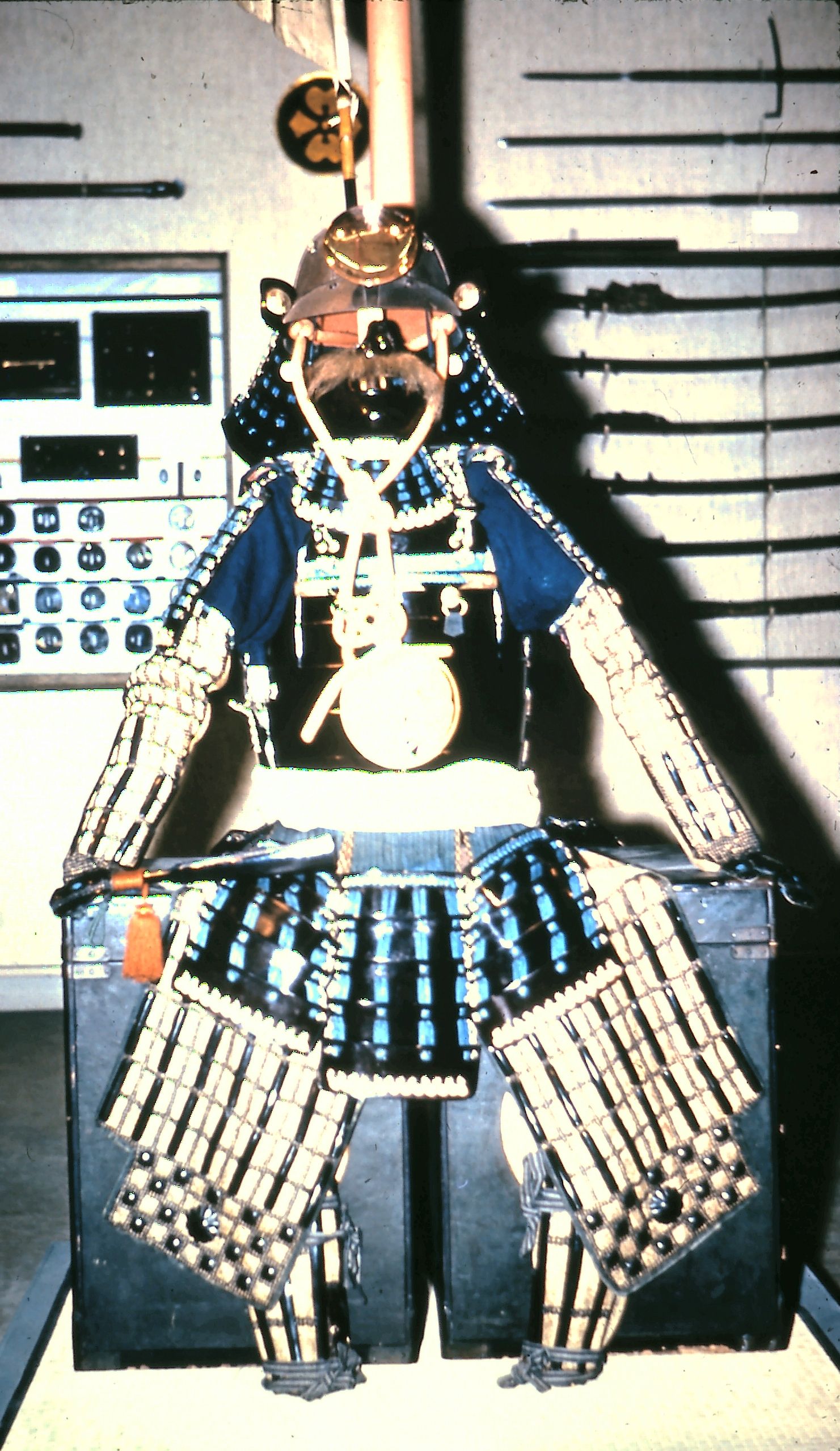

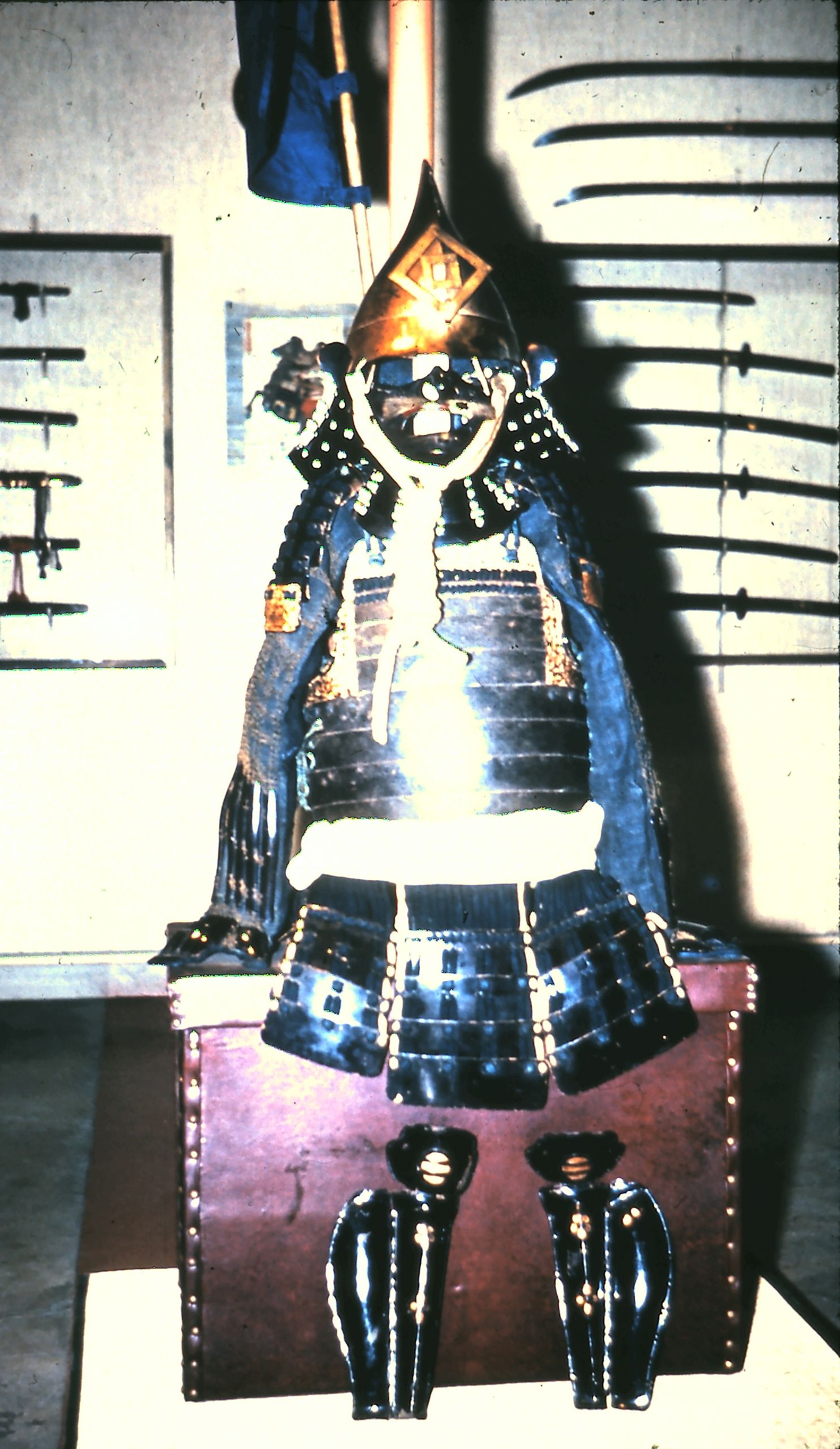

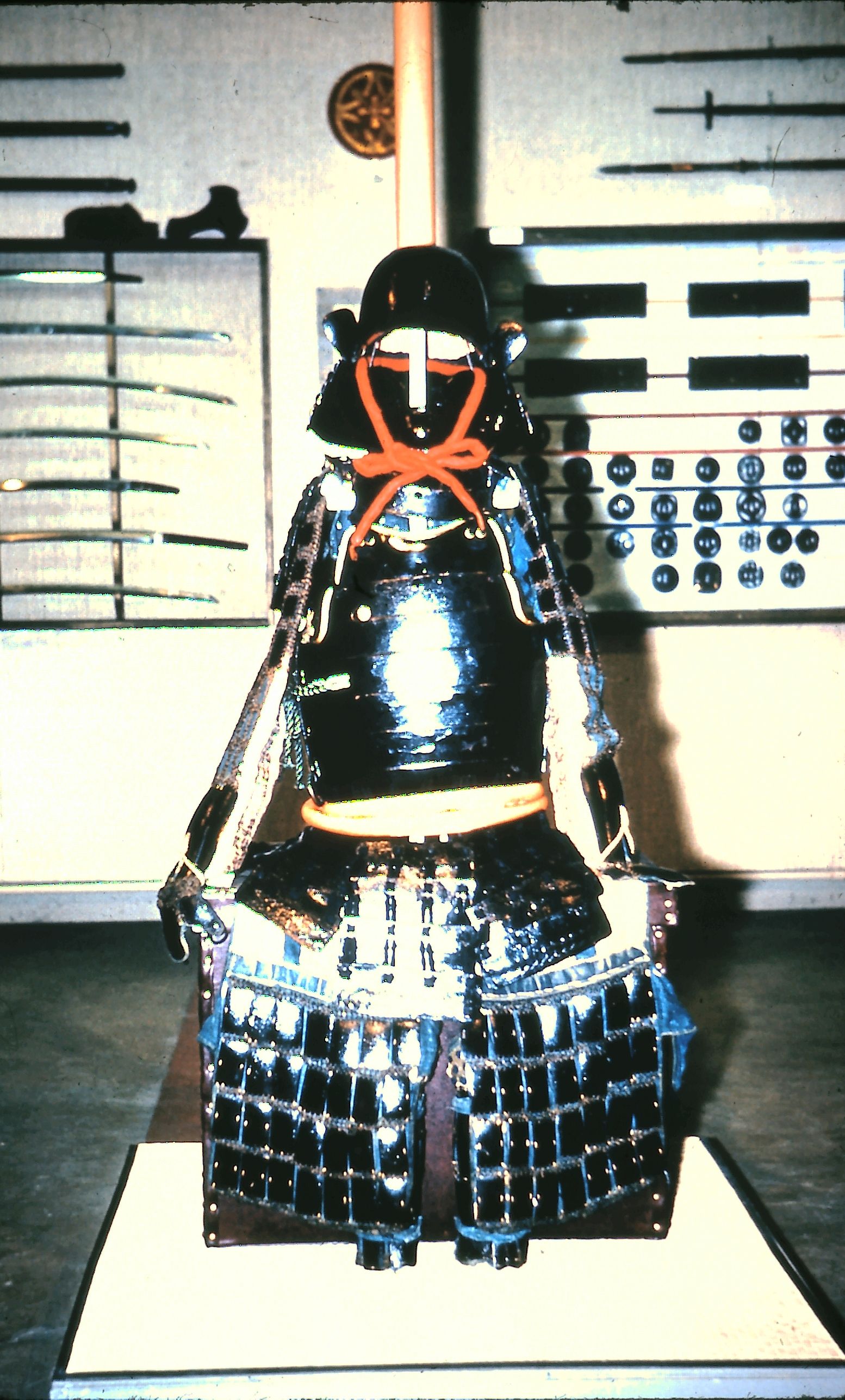

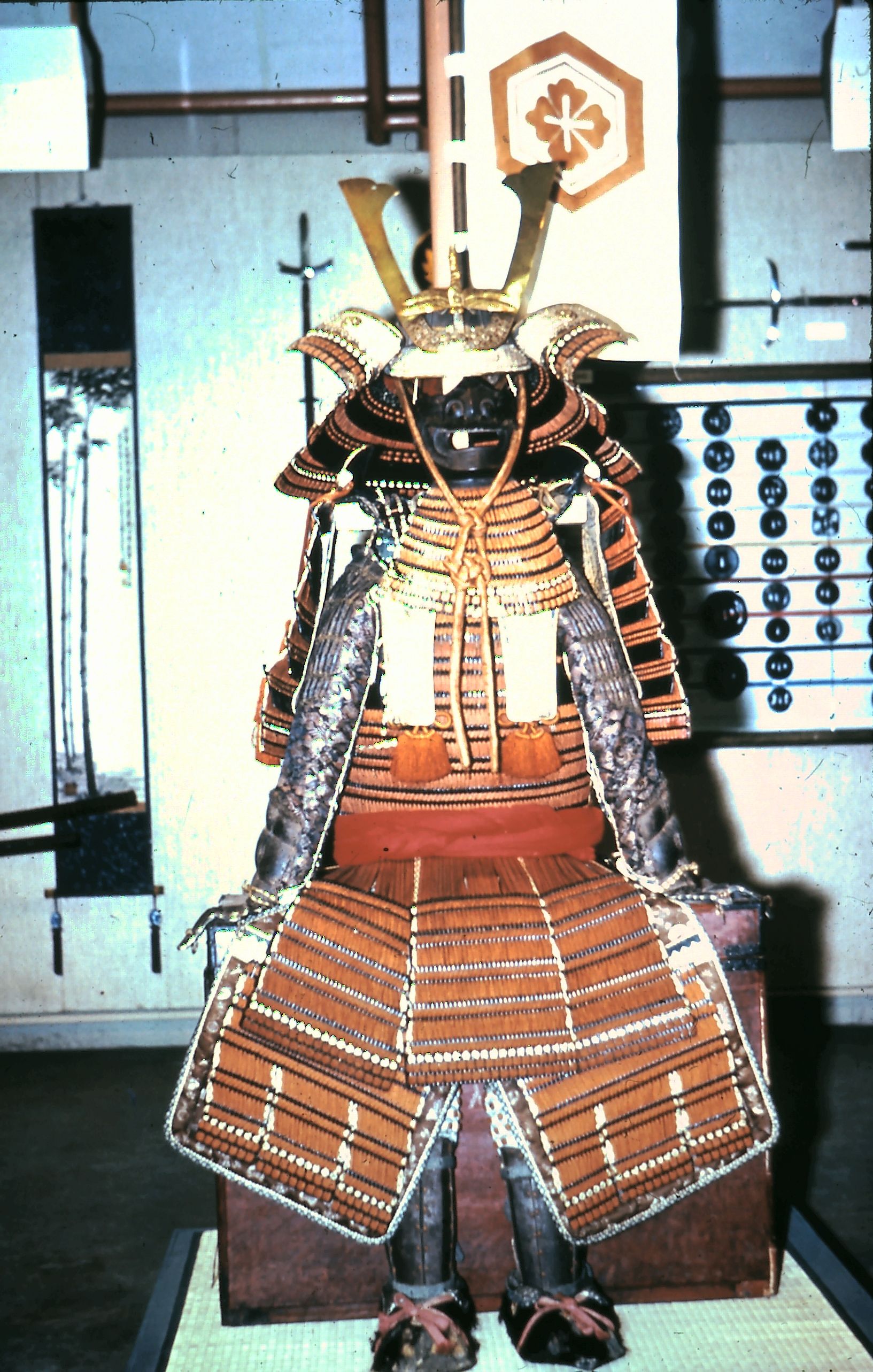

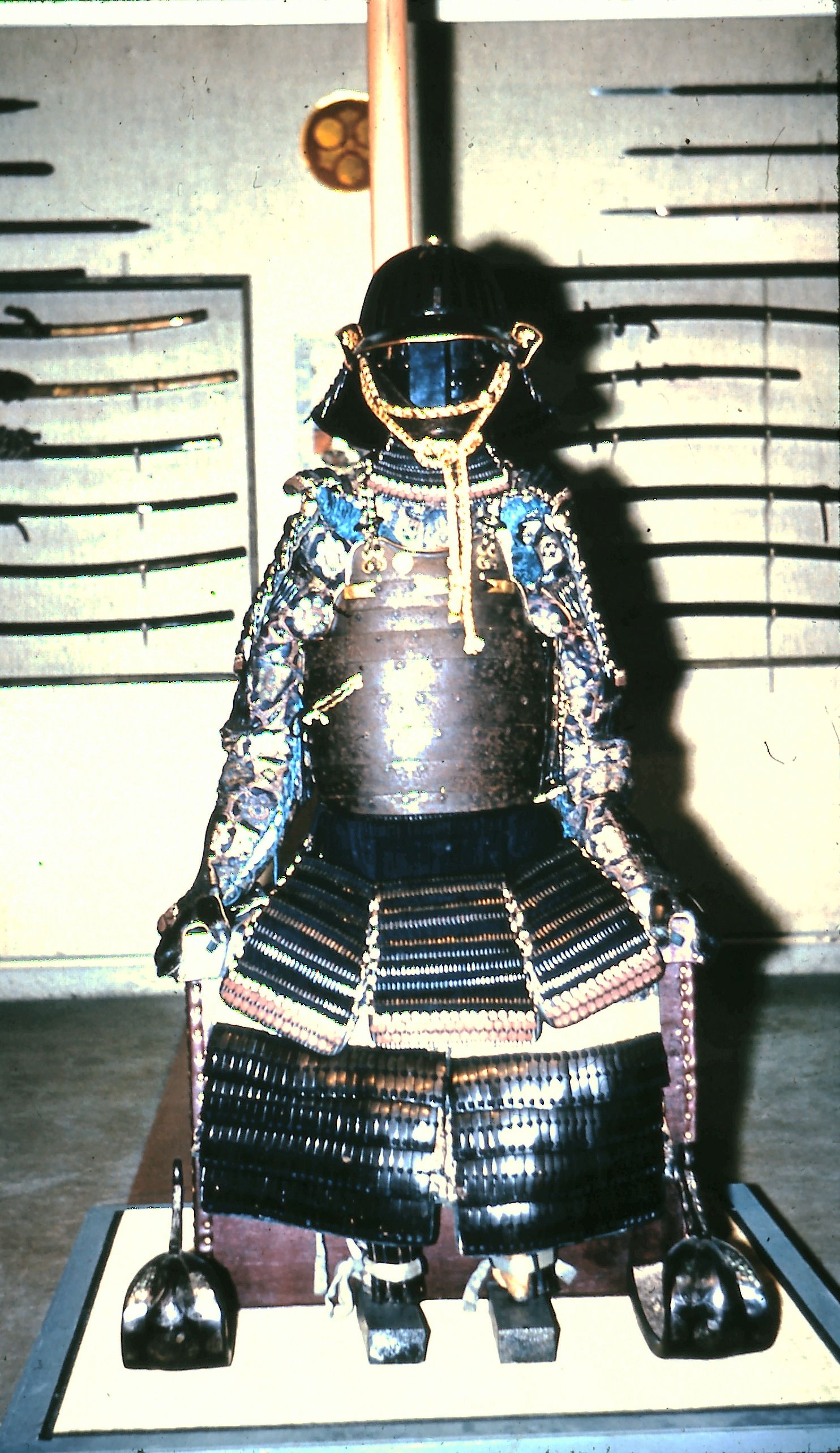

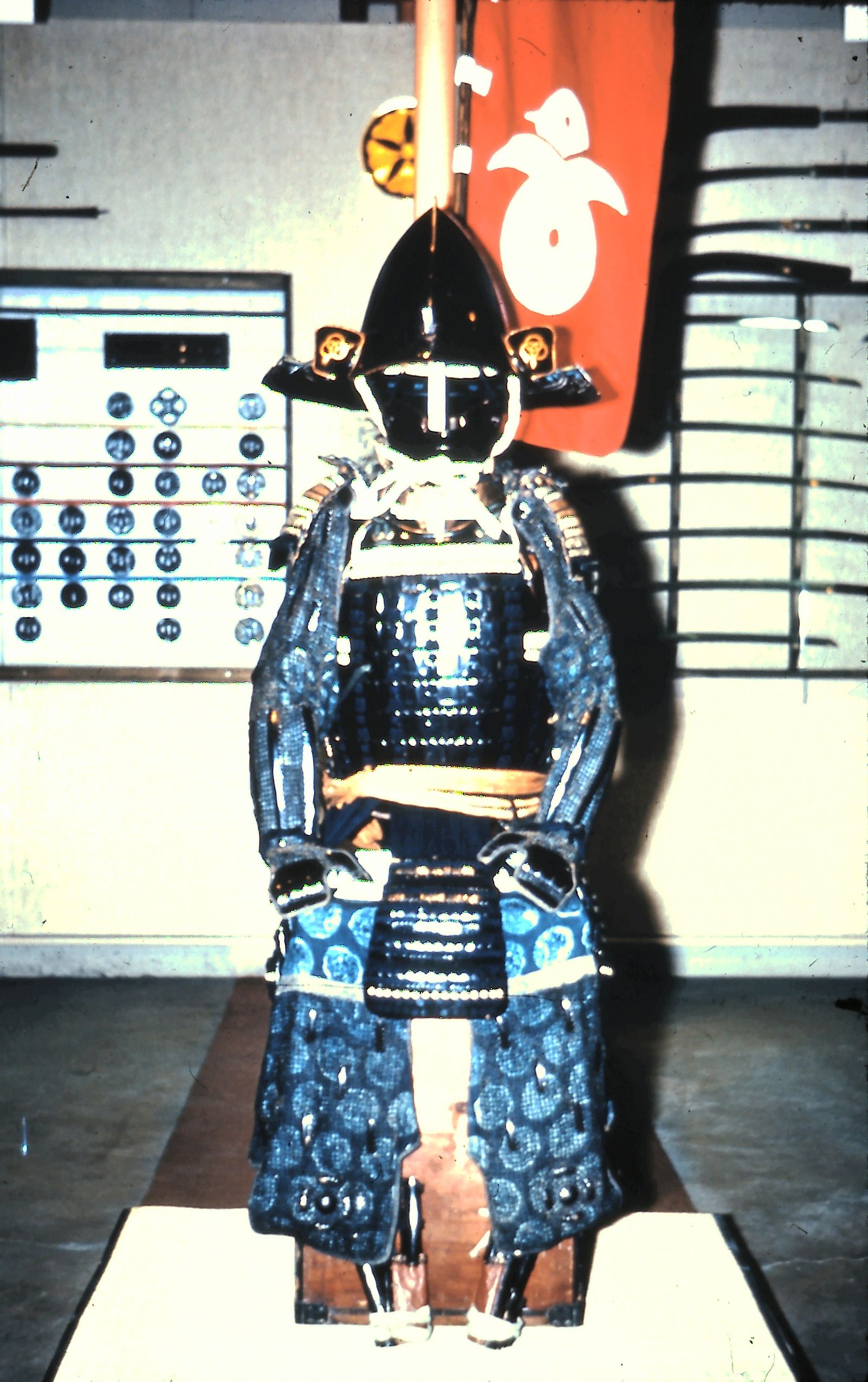

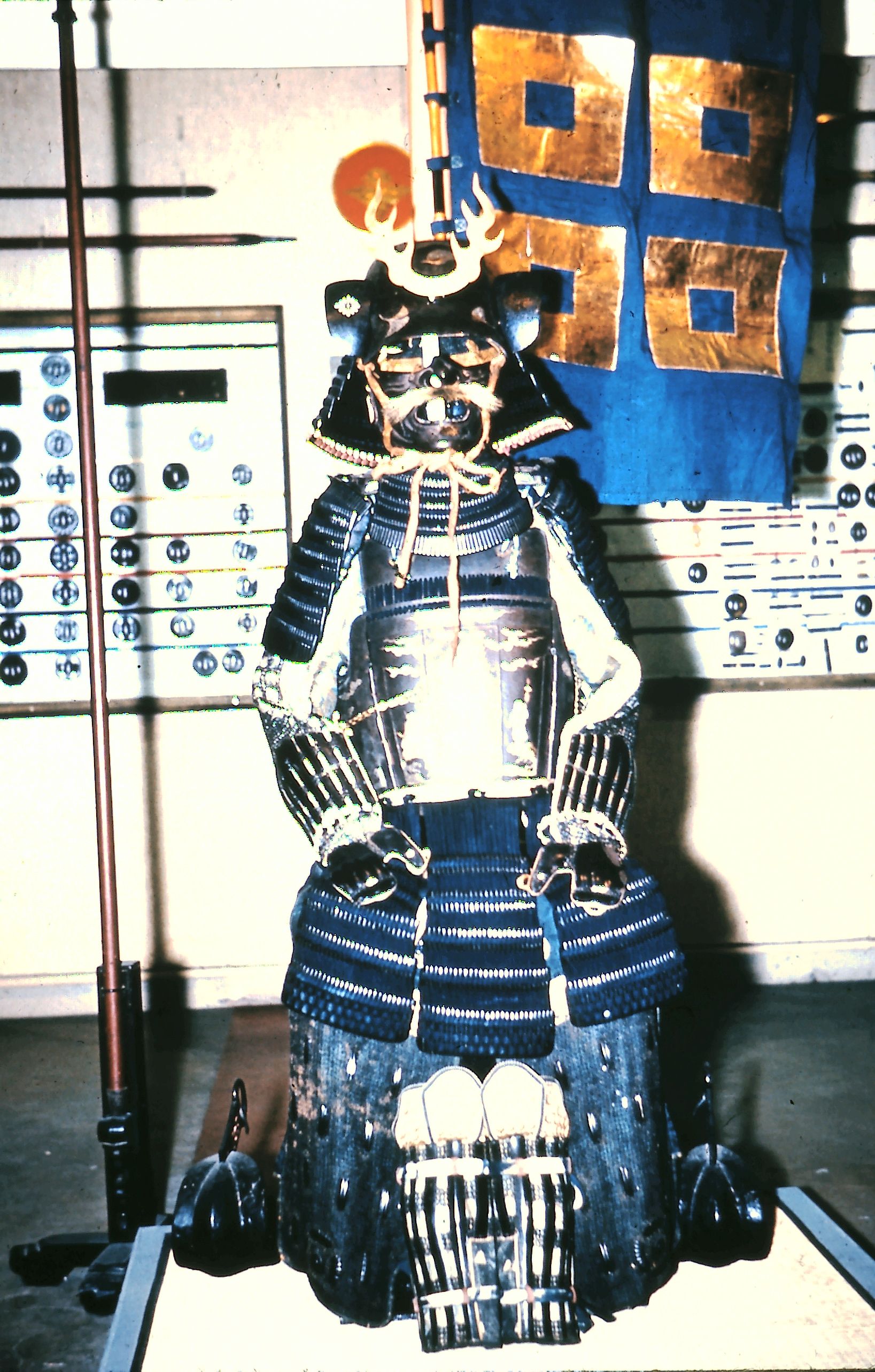

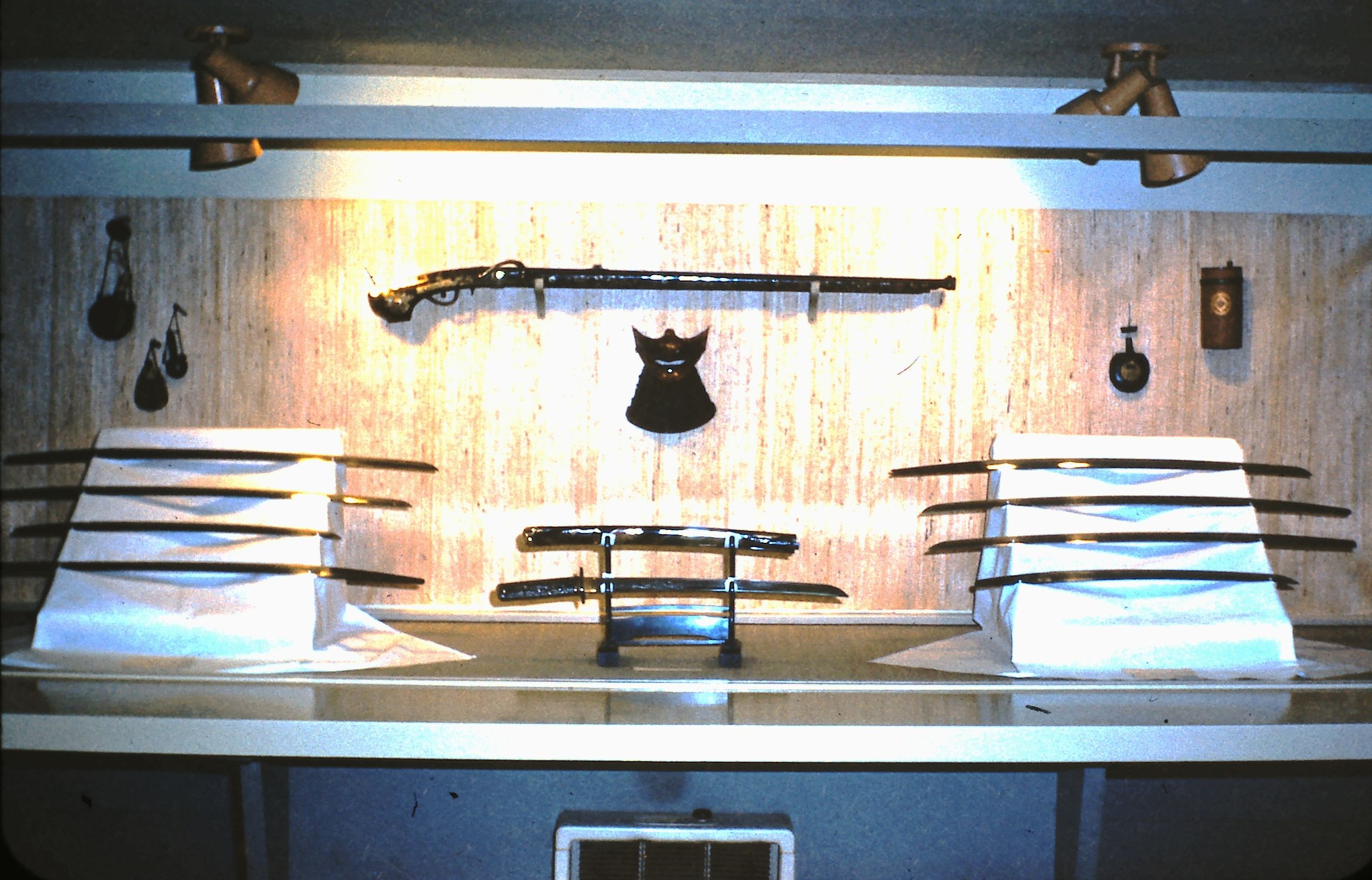

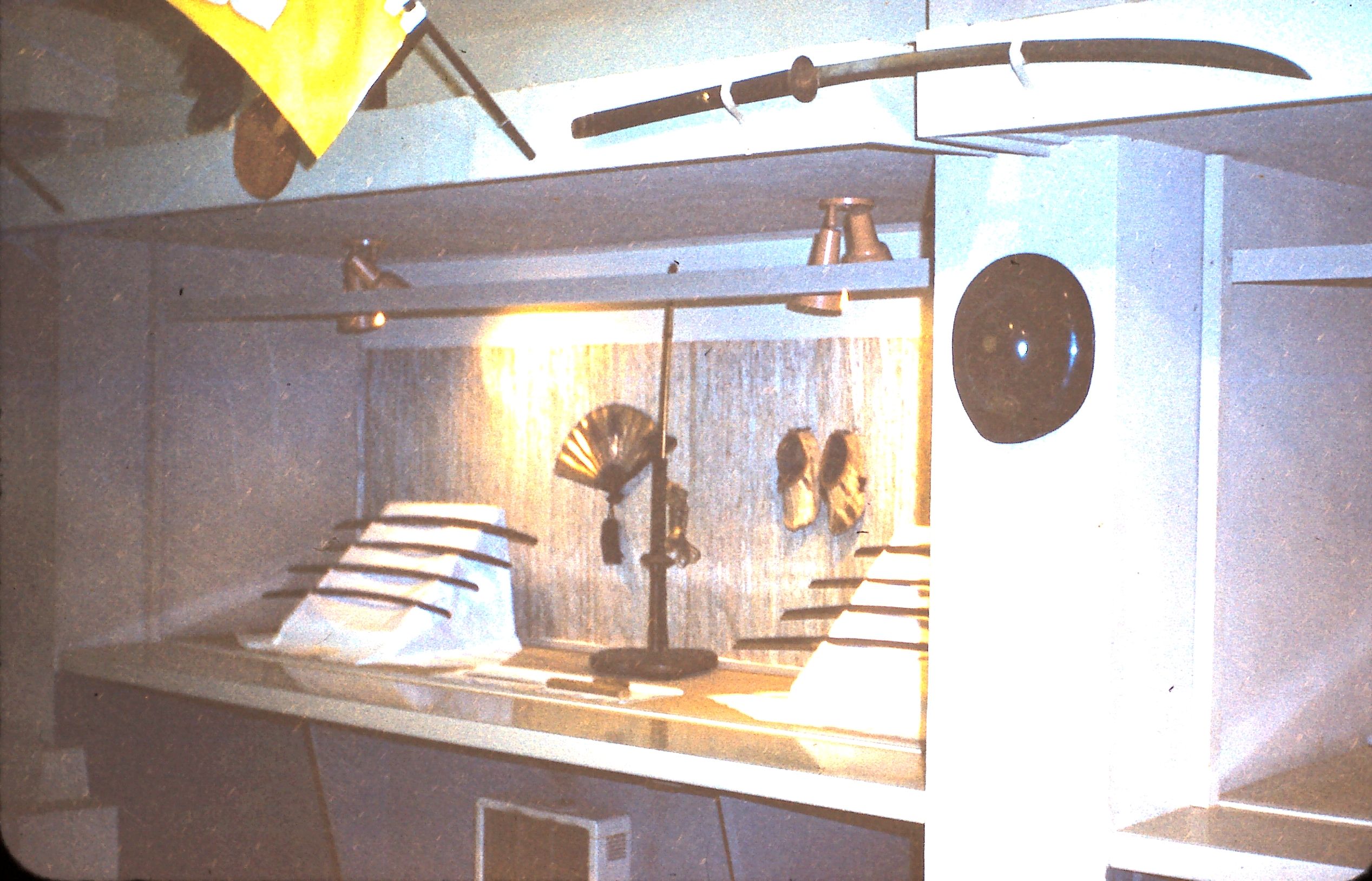

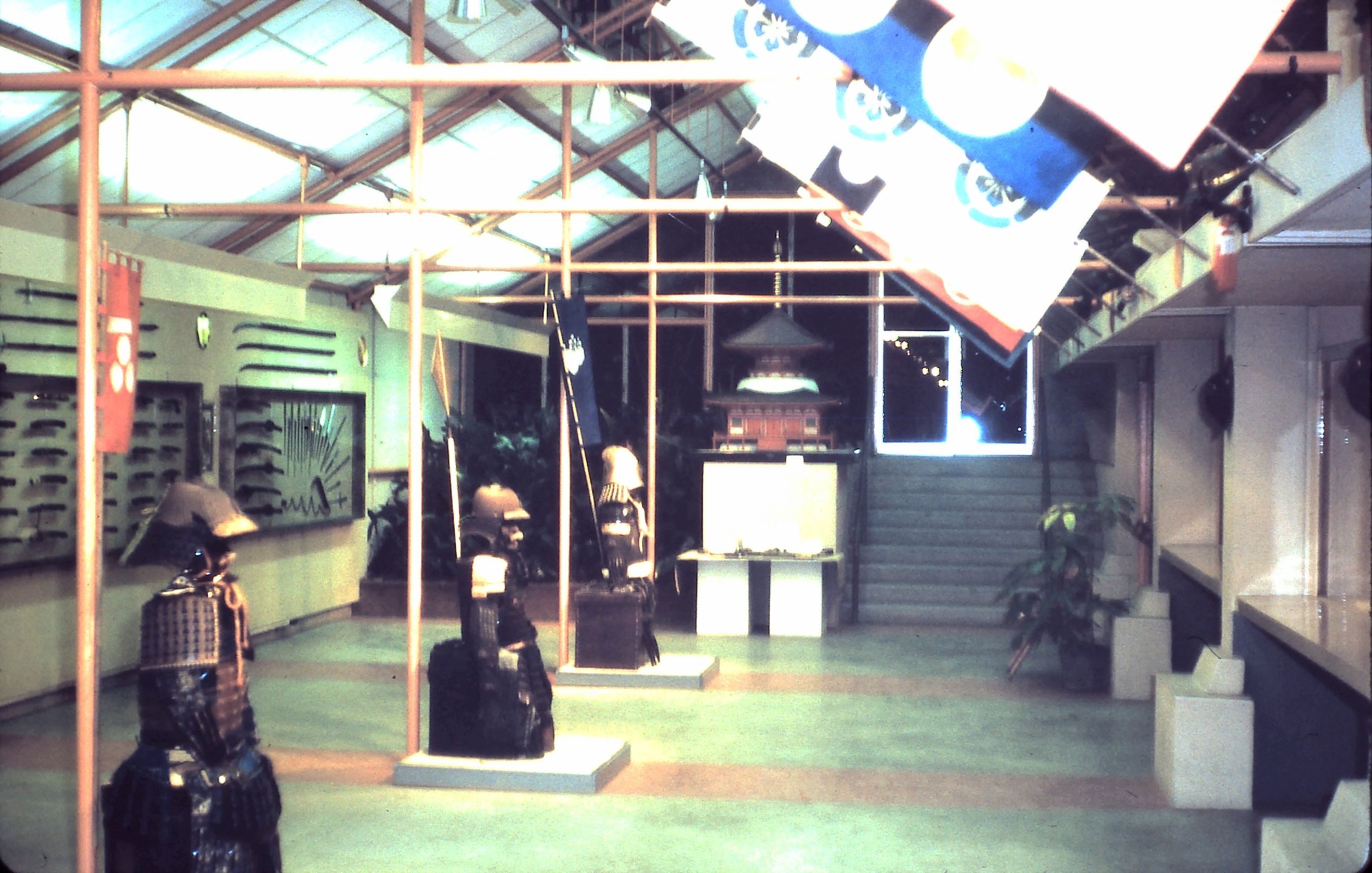

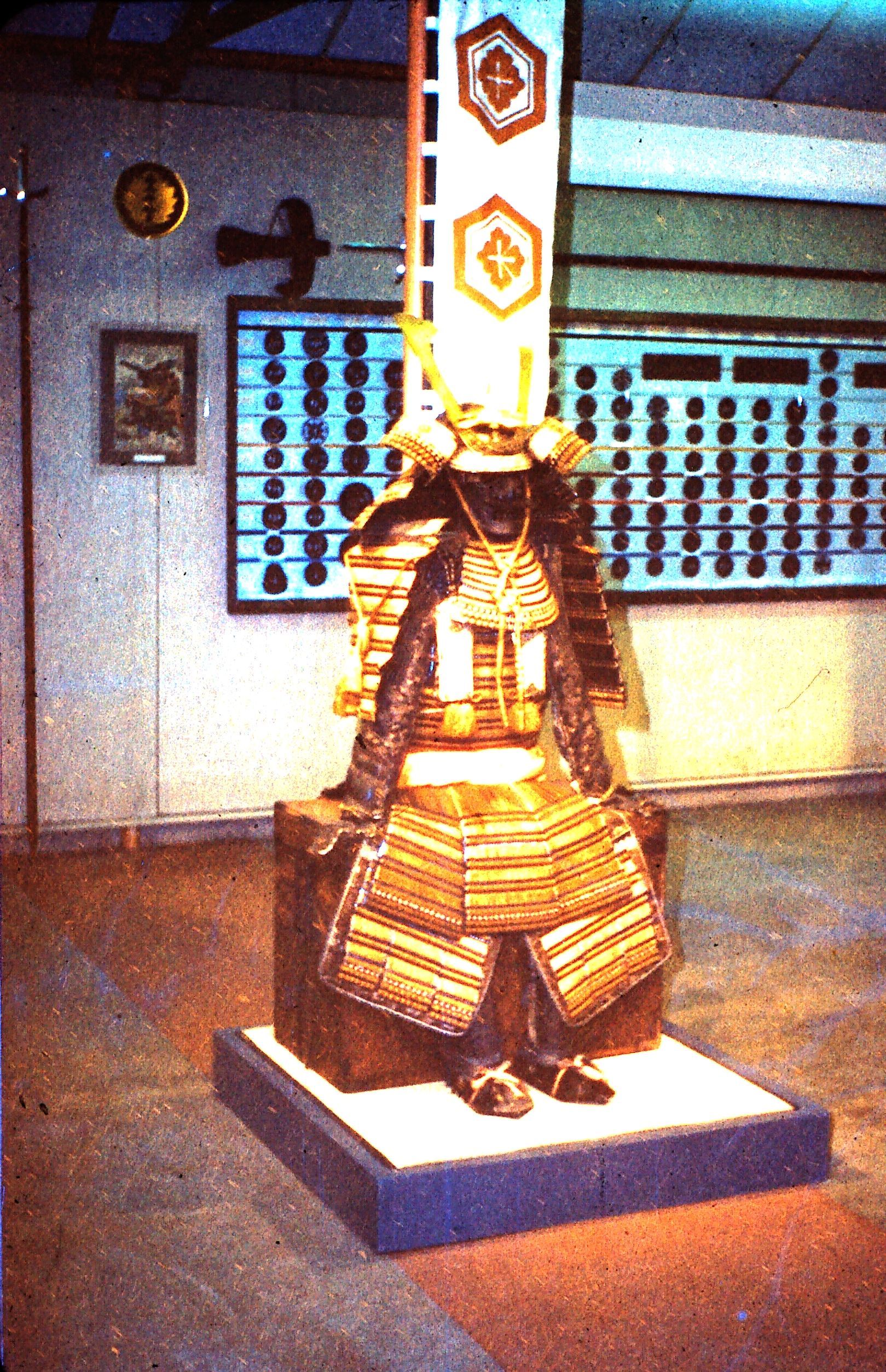

Armor on display |

Fritz Miller, Hartley, George Vitt, Carolyn Frankenheimer,

& Willis Hawley |

Mr. Taromatsu Okano & a Dai-Sho of fabulous mounts to a pair of

fabulous

swords, both by Sukehiro. |

|

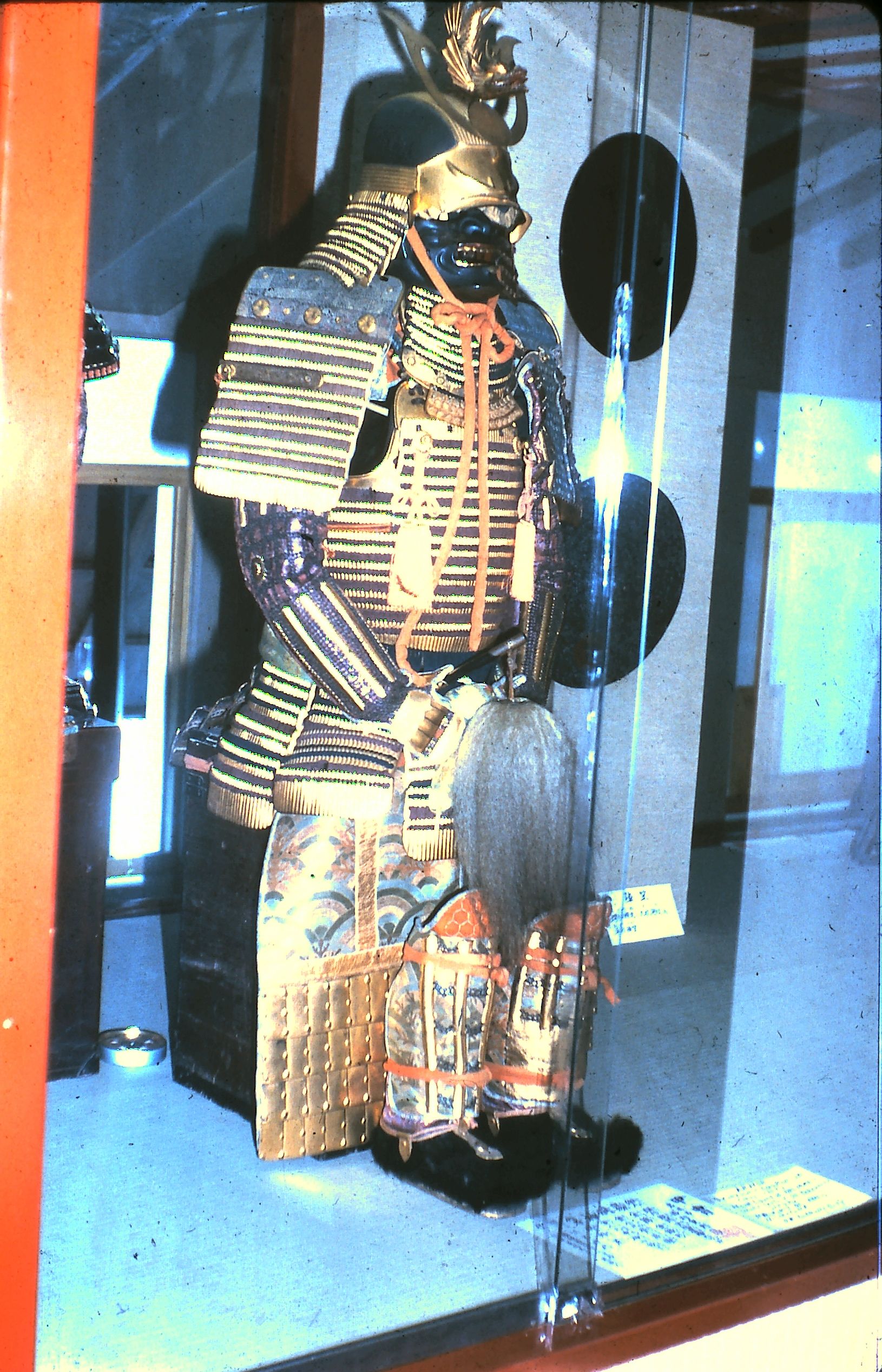

Armor on display |

|

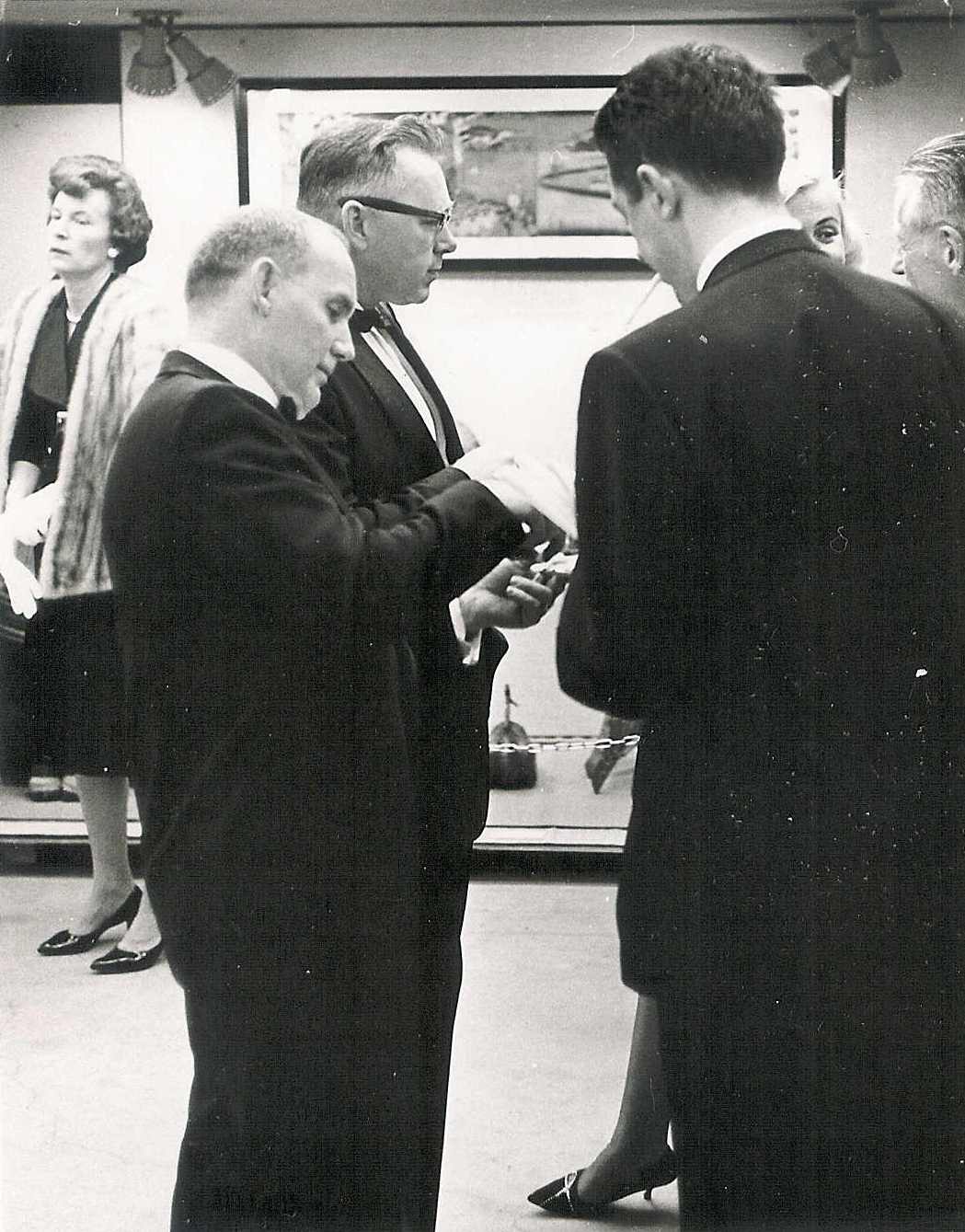

Bob Wainwright, Dean Hartley, Charles Cowdery, & Willis Hawley |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

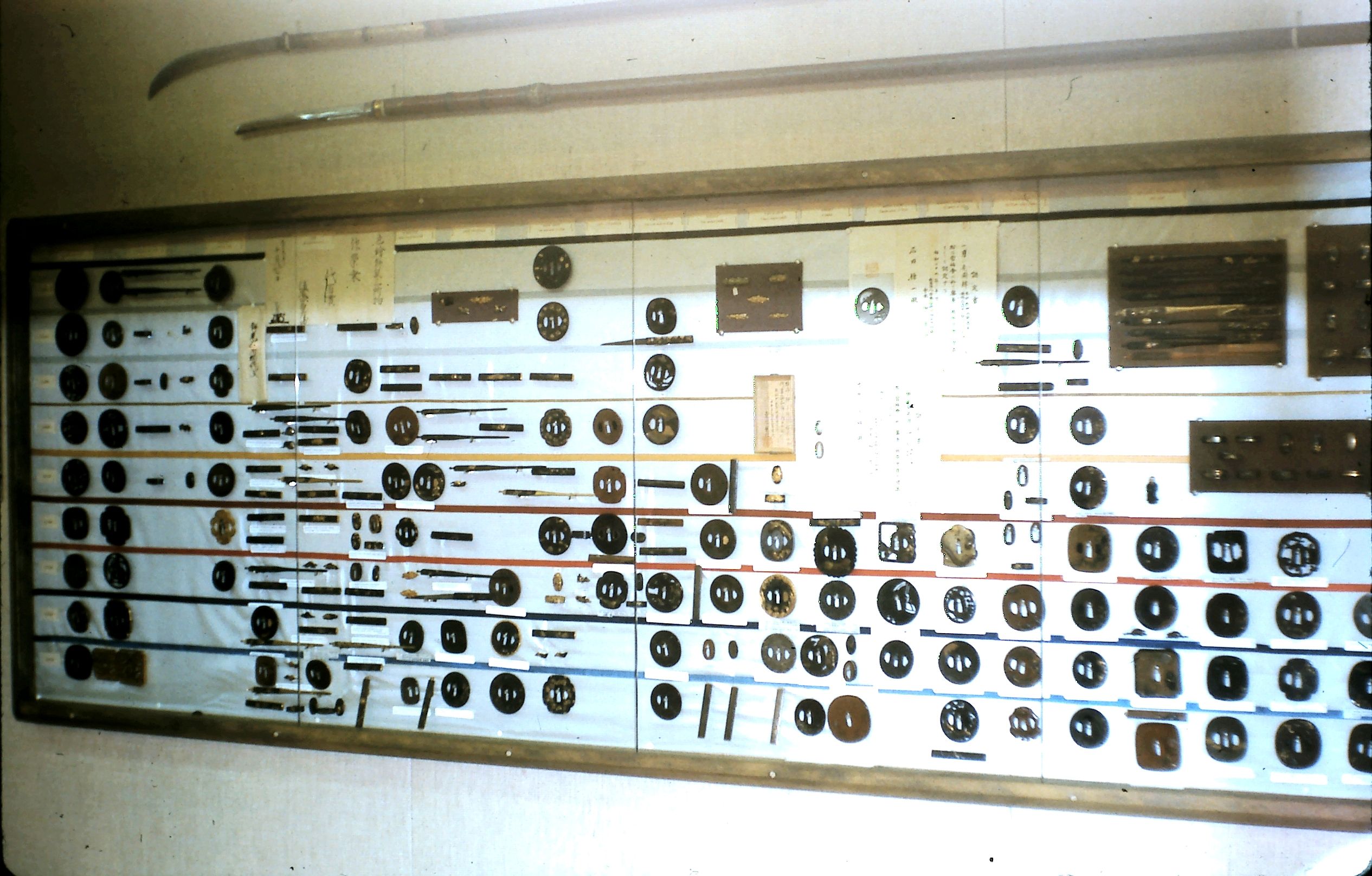

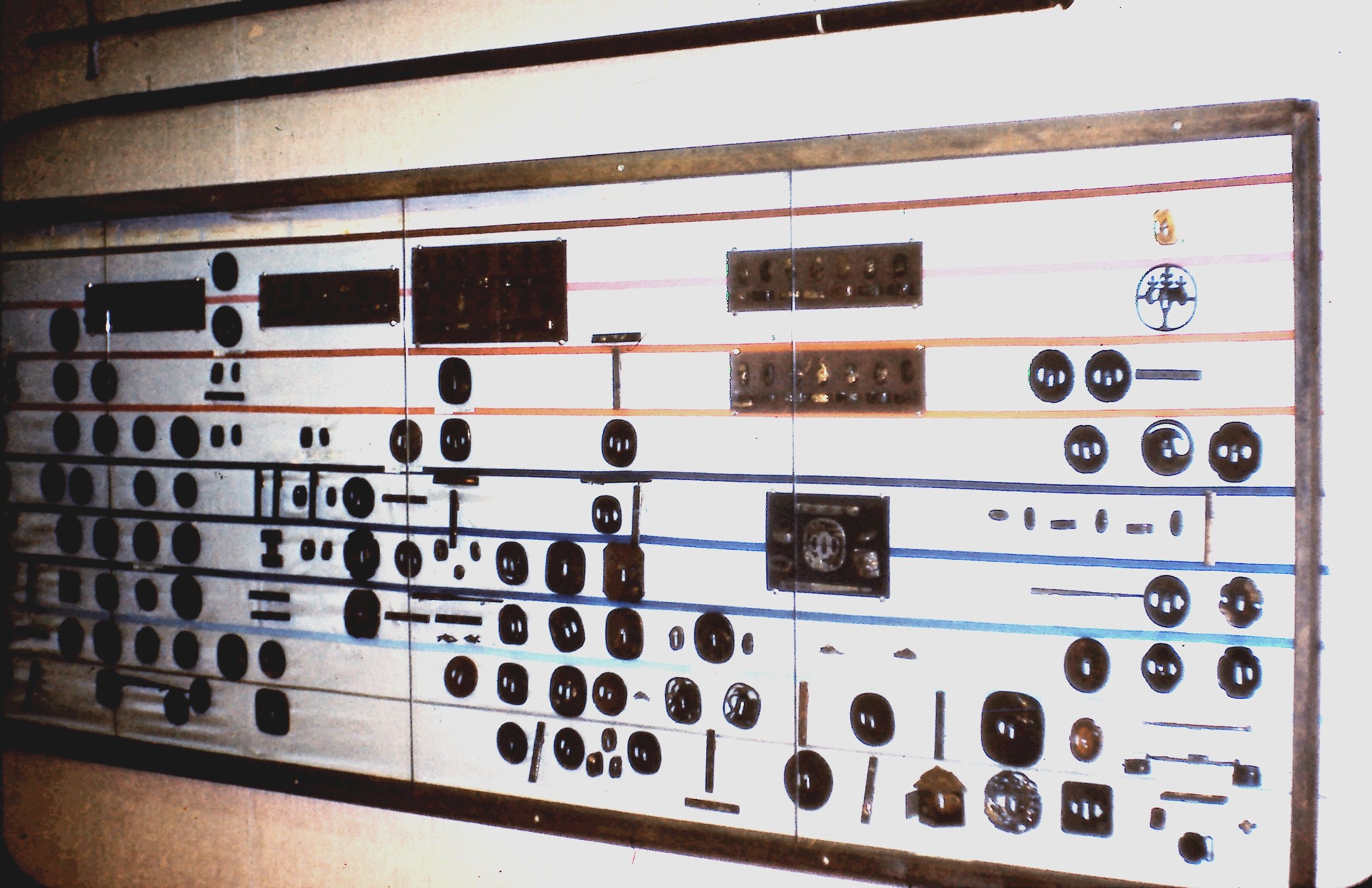

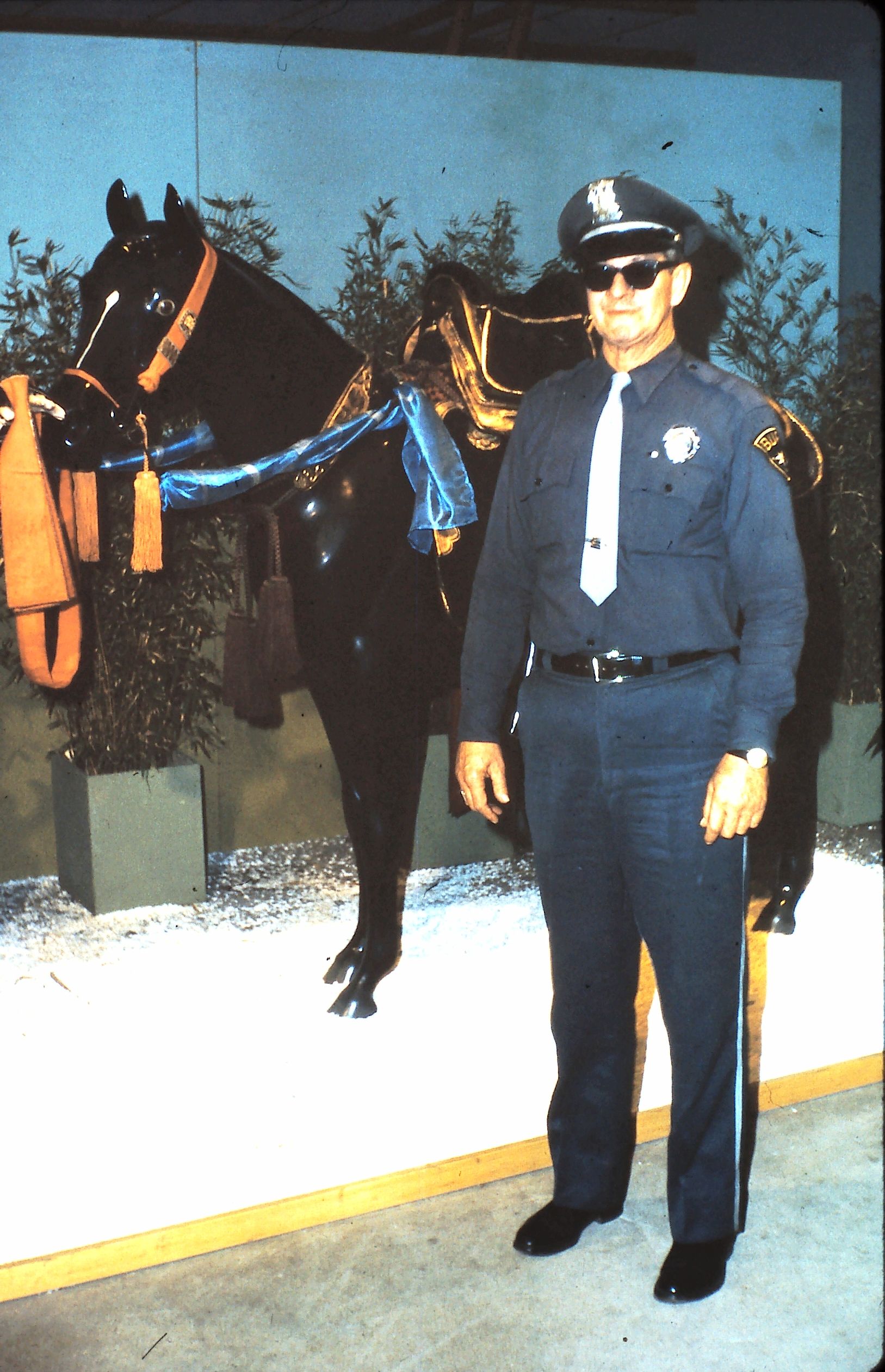

The show in progress |

|

| |

Cover: Painting by Walther G. von Krenner |

The Sword with

pictures of the sword displays

Patrons with additional pictures of the exhibition

In Japan the sword and its associated fittings have for

centuries been regarded as an expression of the highest art, worthy of the

consideration of an Emperor and, in fact during the early thirteenth century,

the Emperor Go-Toba participated in the creation of masterpieces which approach

the zenith of sword excellence. The west has commonly regarded them as

curiosities, the products of a craft, and equated them with other swords. It is

the hope of the Southern California To-Ken Kai that this exhibit may in some

measure contribute to a better understanding of the Japanese sword and a more

correct evaluation of its artistic values.

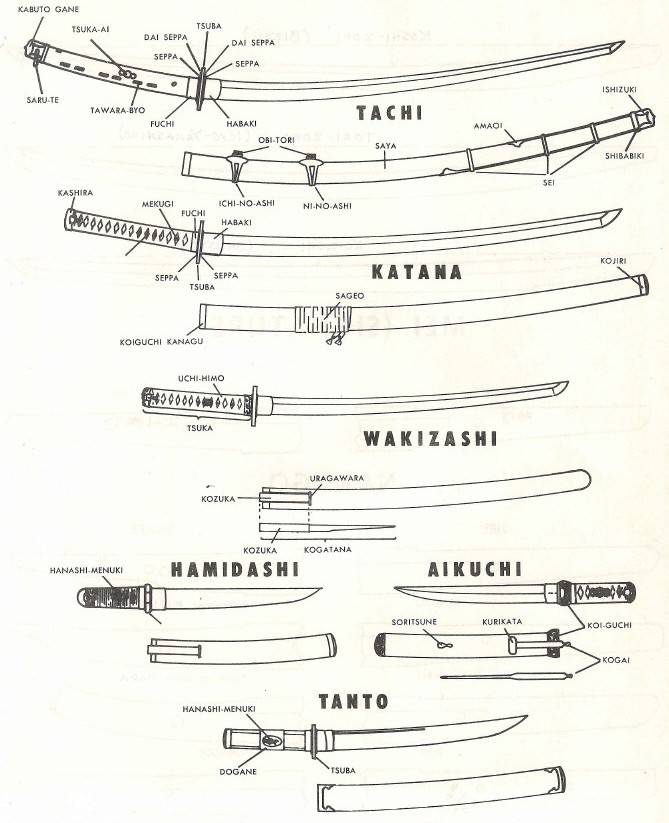

The descriptive terminology in this catalogue is the language

of the sword and recourse to the glossary of terms will, for the uninitiated, be

absolutely necessary. From very early times expertise on the sword was the

exclusive property of families of sword experts, principally the Honami, who

maintained their knowledge as a closely guarded secret. Thus, the language was

intended to obscure rather than reveal. Further, the idiom is one which does not

lend itself to easy translation, there being no equivalent terms in the English

language.

Chronology is arbitrary since there is no close agreement

even among historians. The chronological divisions are in the main political,

the single exception being connected with sword history. Most divisions in sword

history coincide with political divisions, there being a strong interconnection

between the two.

It is to be regretted that all of the material exhibited

could not be included in the catalogue. Examples were chosen not only on the

basis of quality but as specimens representative of a particular time and

school. Selection was made from an aggregate total of over two hundred swords

and seven hundred tsuba exhibited.

The study and collection of the Japanese sword and its

fittings is attracting a growing list of followers from widely assorted

backgrounds. Their common interest is an appreciation of the unique skills and

creative talents which rank the master swordsmith and the ciseleur with the

enduring artists of this and future times. Their rights to such distinction are

evident in the pieces chosen for display in this exhibit. Many are rare

examples, many are seldom seen masterpieces ... all are fine examples of the

art.

Our deep appreciation is extended to those institutions and

individuals who so generously made their collections available to us, to the

people without whose unselfish aid this achievement could never have been, and

to the Los Angeles Municipal Art Patrons for their unremitting support of our

hopeful effort.

F.C.M.

Editor's note: The actual catalog contains the Japanese characters for the

smiths' signatures, which are not reproduced here. Also, some of the pages have

been rearranged to take advantage of the web format versus the page format of

the original catalog.

1.

Standing figure of a warrior in full armor,

Kofun Bunka Period. |

2.

Armor: red laced Oyoroi (great harness) of the Edo period in an

early style. |

Armor on display at the exhibit.

Return to the Table of Contents

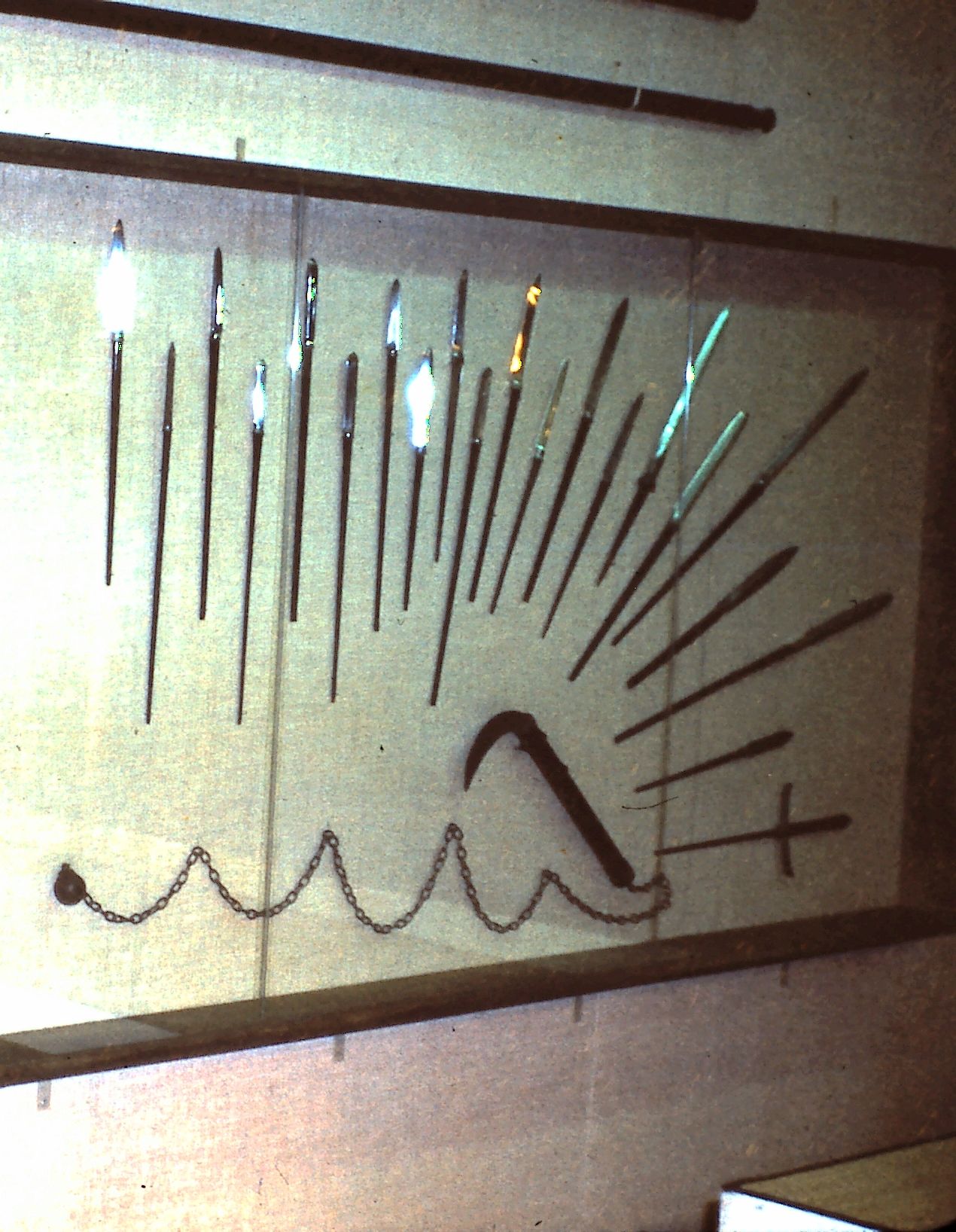

Preserved within the confines of Todaiji temple in Nara is an

ancient storehouse founded in 756 A.D. as a memorial to the Emperor Shomu. In

this relatively fragile structure all of the Emperor's personal possessions,

together with gifts of the court, have remained inviolate to this day. Included

among the treasures dedicated were swords, armor of plate and scale, bows,

arrows, pole arms of several types, and other military equipment. During the

Oshikatsu rebellion in 764 A.D. the weapons were removed to the palace by

imperial command and much was lost in the subsequent fighting. The precious

remainder serve as the principal source of information about the weapons of the

period. Among the rest, forty nine long swords were left, their blades bright

and shining today. These swords exhibit every important characteristic found at

the culmination of the swordsmiths' art five centuries later. Although the sword

underwent modifications during the succeeding centuries, the shape and

underlying principle remained the same. Thus, old swords remained serviceable

until the last and were carefully preserved, both for their utility and because

of the deep reverence which the Japanese feel for the blade.

All swordsmiths, regardless of the place or time, have been

confronted with the problem of creating a blade which would neither bend nor

break and yet would cut well. The unique Japanese solution to this problem was

the development of what may be called a composite blade. The basic principle of

the Japanese sword is the support of an extremely hard edge steel by means of a

tough resilient back. This was achieved by enclosing the edge steel in a mild

steel back, by wrapping a mild steel core with edge steel, or by complicated

constructions utilizing appropriate steels.

Traditionally, Japanese swords are classified into five

schools or methods named after the province in which they originated: the

Yamato, Yamashiro, Bizen, Soshu, and Mino, listed in the order of their

historical appearance. They were, simply, different paths to the same goal

differing only in technique. The basic principles were identical. All Japanese

swords are composed of steels which were forged, folded, and reforged a number

of times consistent with their utility, edge steels fifteen to twenty times and

the milder steels six to eight times. Sometimes during the folding the grain of

the steel was crossed. Heat treatment was accomplished by coating the blade with

refractory clay which was thinner at the edge, bringing to heat, then quenching

in water. The area at the edge, having less insulation, cooled rapidly and

became hard. The back, covered with thicker clay, cooled slowly and became

tough. At the same time the differential cross-sectional thickness in the blade

caused it to assume a curve.

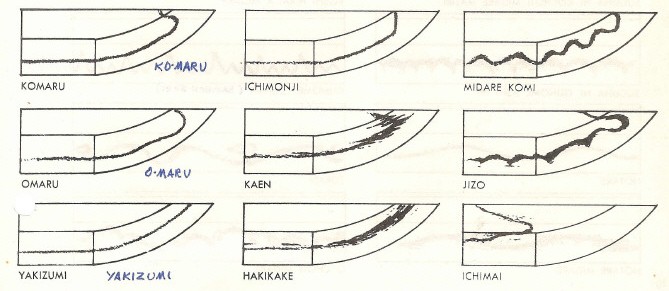

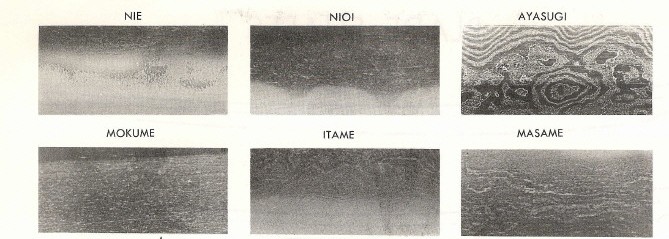

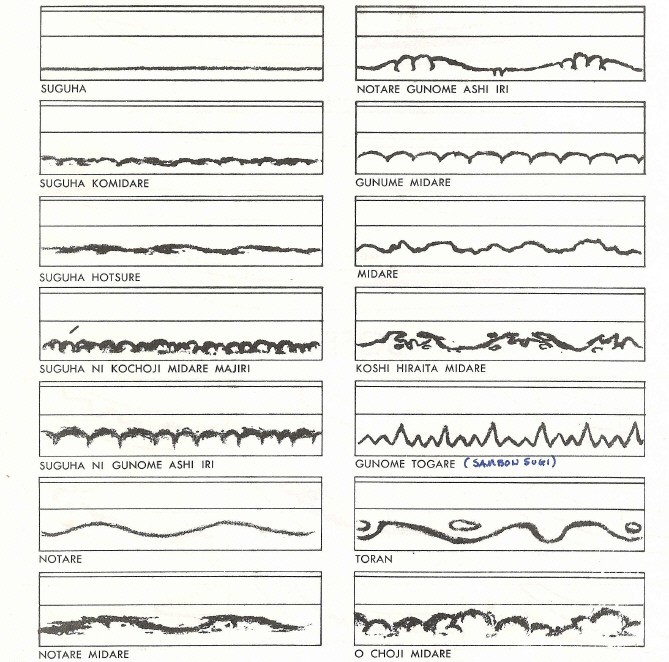

The spectacular polish found on Japanese swords not only

enhances their beauty by making visible the tempered edge pattern and the

details of forging which are so important to an aesthetic appreciation, but

makes possible a visual evaluation of the essential qualities of the sword. If

the grain created in the forging process is small and the heat before quenching

high, as can be determined by the presence of a wide tempered edge and coarse

nie (mirror-like particles of Martensite), the blade will be brittle.

Conversely, if the grain is large and the tempered edge narrow and composed of

nioi (cloud-like Martensite) then the blade will be soft. All of the elements

involved in the making of the sword must be compatible, the grain of the steel,

the temperature of the water, the thickness of the clay, and the heat. An

infinite number of correct combinations are possible. Steel, the fabric of which

the sword is composed, possesses important values of its own entirely separate

from other considerations. It may be translucent deep and clear, a thing of

transcendent beauty, or coarse, hard and dry, a product of haste and

opportunity. Here the work of the smith stands most clearly revealed and his

work defined.

The Japanese, as a people, are unique in their awareness of

beauty. The society is permeated with this consciousness and there is a constant

preoccupation with the aesthetic. Blades can be expected to reflect this

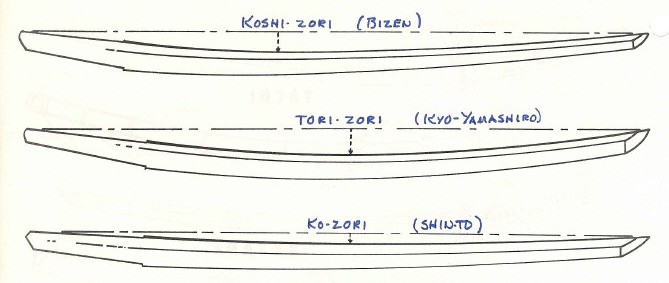

sensitivity. The first consideration in the judgment of a sword is the shape:

regardless of the period and the changing styles, it must be aesthetically

satisfying. Swords made during the Heian period, with its strong overtones of

effeminacy, and those made during the virile masculine Kamakura period were and

are subject to the same rigorous aesthetic canons, although their shapes may be

vastly different. Swords lacking form and style, such as those mass produced

during the latter half of the Muromachi period for common use, are passed over

by the discriminating collector. Similarly, the phenomena seen in the surface of

the steel must be in taste. Pictorial representations in the hamon found during

the Genroku era are considered to be merely examples of a limited virtuosity and

lack depth and sincerity. The collector must differentiate between swords which

are kept as representative of a type and those which are worthy of an aesthetic

appreciation.

Although swords disappeared from daily use in 1877 with the

promulgation of the Haitorei edict which prohibited their wear, some few smiths

continued to work and, binding the present to the past, blades are being made

today in accord with the highest traditions of this ancient art.

Frederick C. Martin

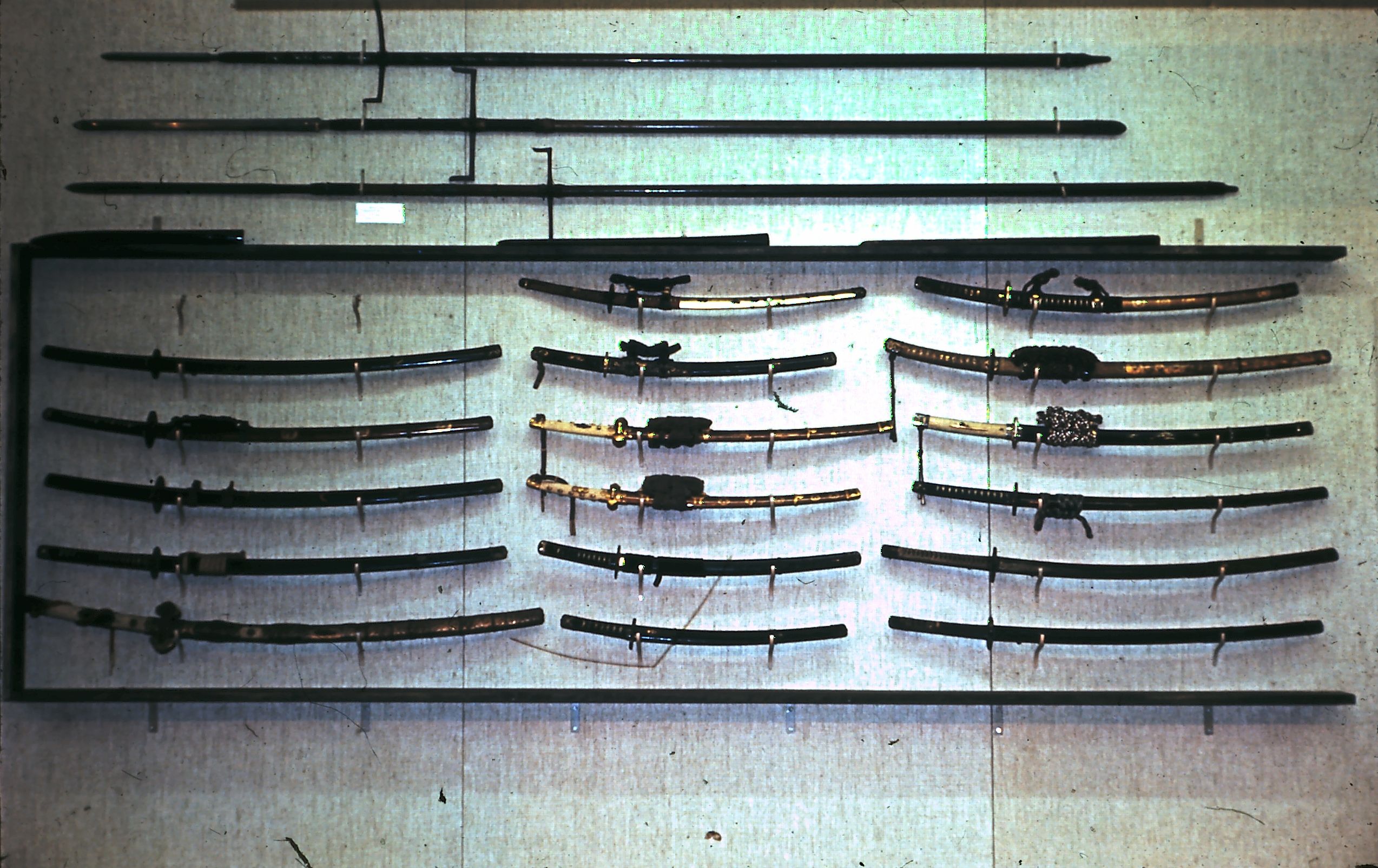

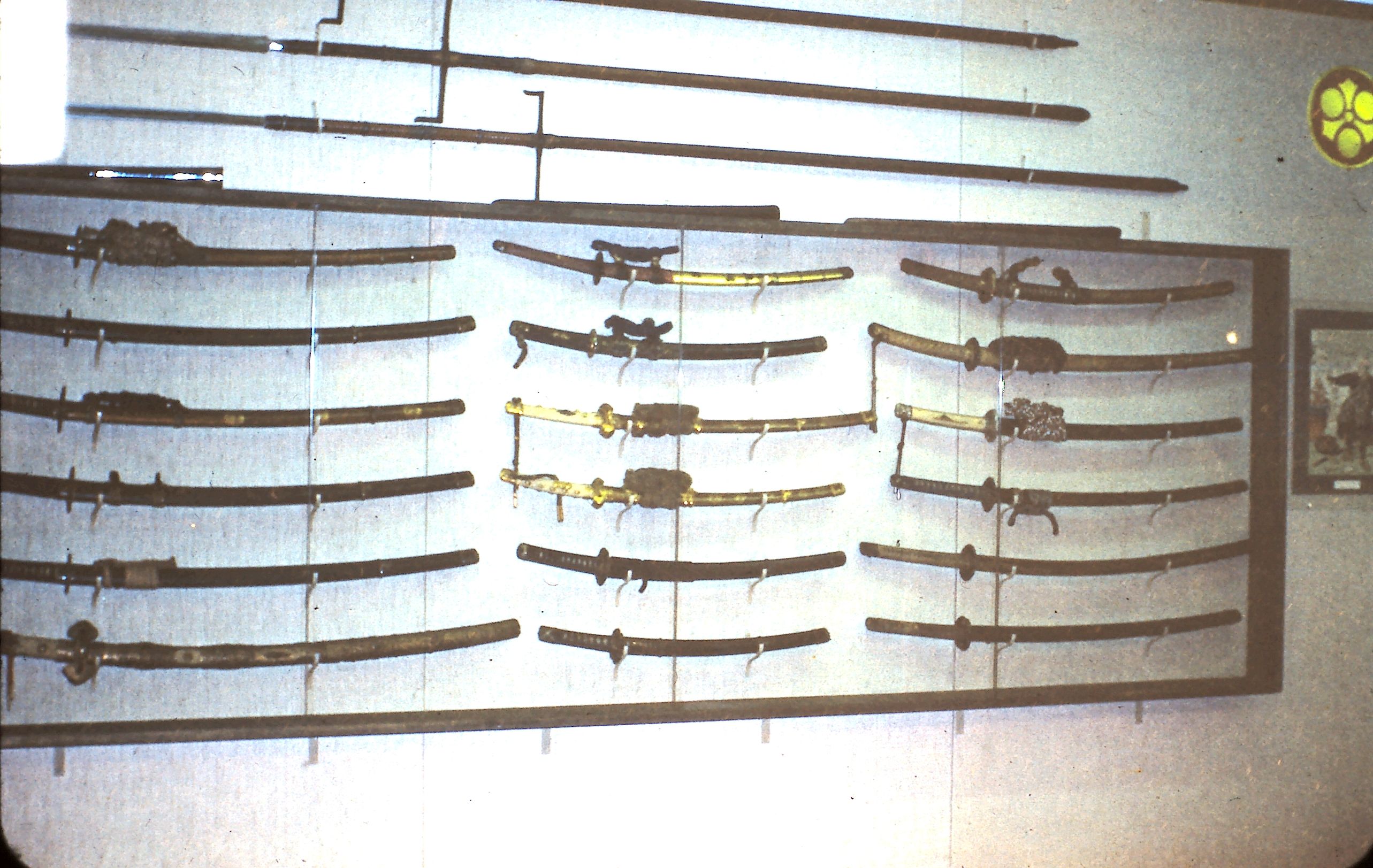

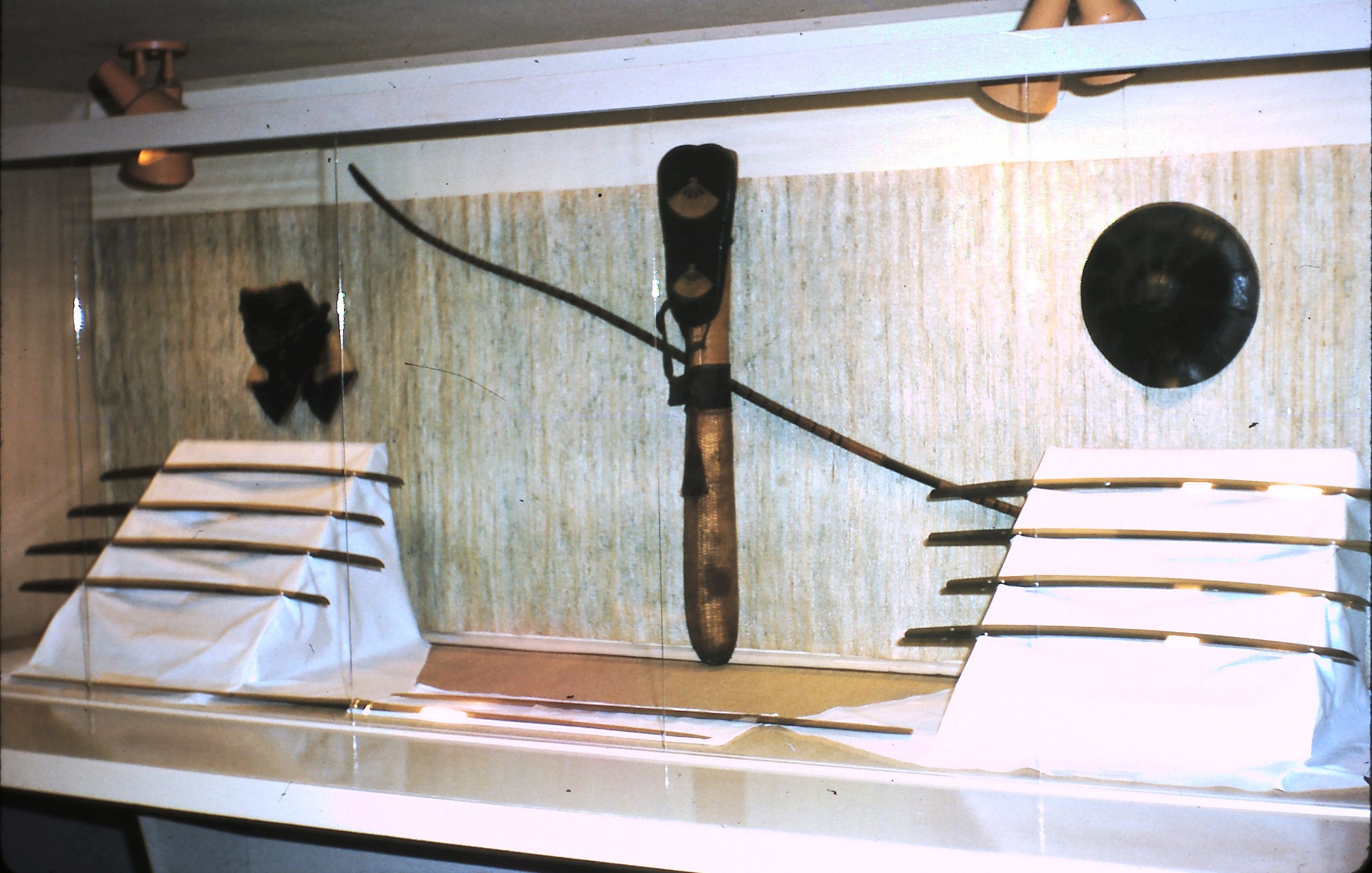

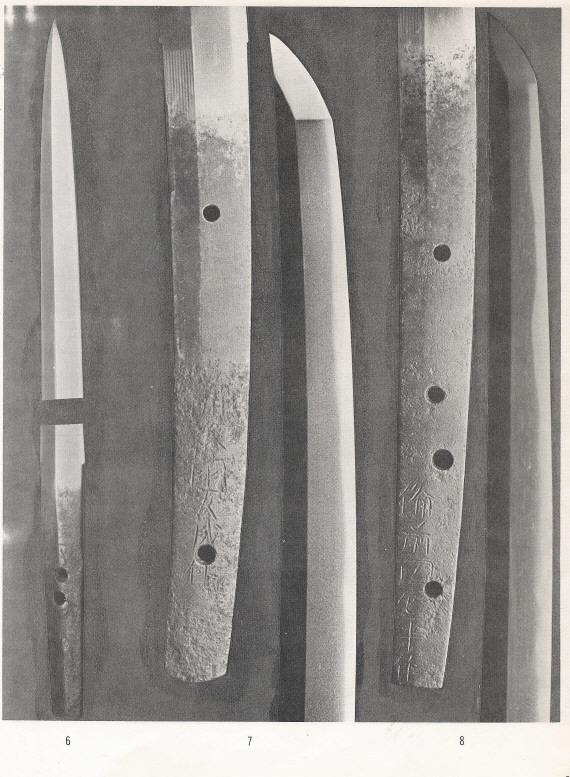

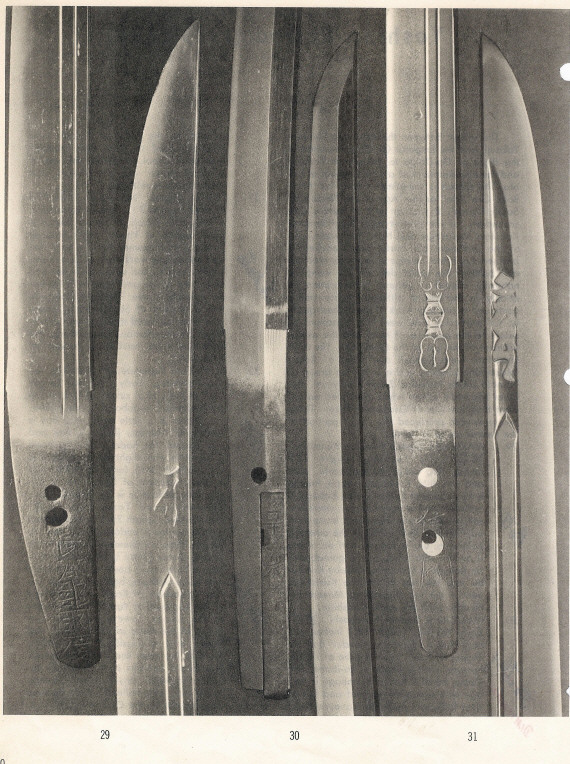

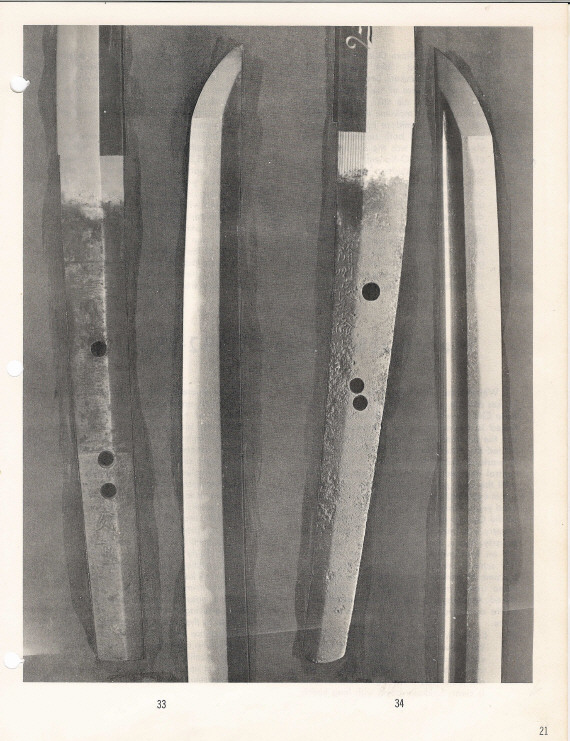

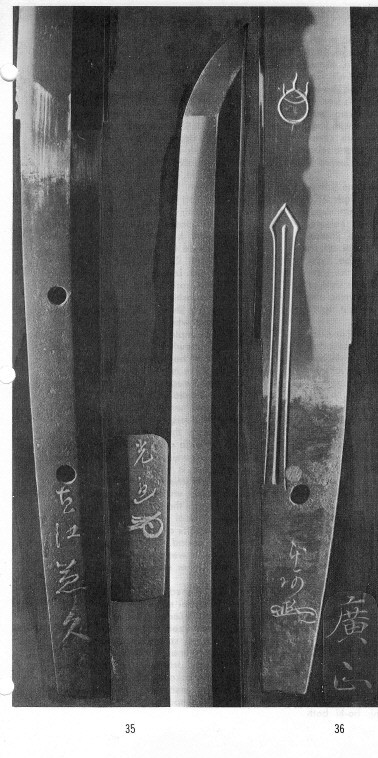

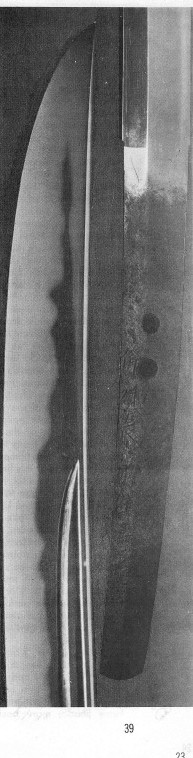

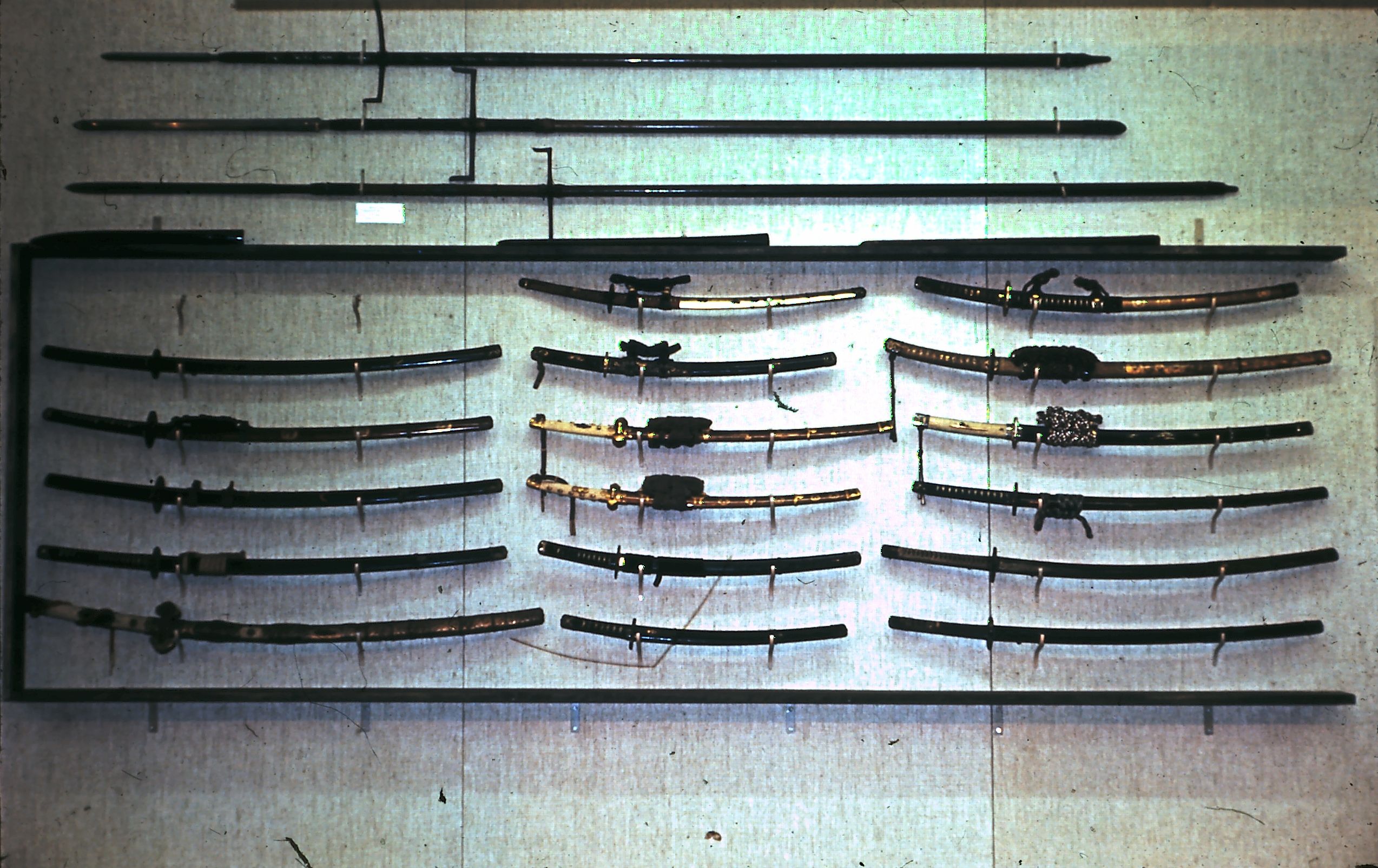

Swords on display at the exhibit, beginning with stages in

the creation of a sword.

The era from the fourth century B.C. to the seventh

century A.D. is called the Kofun Bunka period from the method of interment

of the chiefs and important people of that era in stone crypts, or dolmens,

which were located in burial mounds. Encircling the mound and the moats

which sometimes surround the tomb are rows of fired clay cylinders the

purpose of which is not known. They are called "haniwa" which means "circle

of clay." At the crests of the mounds are found clay figures called "tsuchi

ningyo" which represent retainers formerly immolated upon the death of their

lord. Aside from their obvious aesthetic value, these figures are chiefly

valuable for the information derived from them concerning the dress and

habits of the people of those remote times.

The most important objects found within the tombs are

iron swords. There are several types differentiated mainly by variations in

the form of the pommel and the haft. All have single edged blades, the backs

of which are straight. the mounts of these swords are generally copper

richly gilded and often with patterns in repousse. The tsuba are of copper

covered with sheet gold, iron with inlayed decoration, or simple iron. Most

have pierced trapezoidal openings. With the swords are found iron plate

armor of an advanced conception, horse trappings, bows, arrows with complex

points, and other warlike paraphernalia as well as many objects of a more

domestic utility. All bear witness to a sophisticated culture highly

advanced technically and artistically.

-

TSUCHI NINGYO Standing figure of a warrior in full

armor (illustration above). Differing from most figures of the period,

the armor is conventionalized and lacks detailing. It conveys a most

spruce and elegant feeling. Found near Fujioka in Gumma prefecture.

-

KEITO TACHI (not illustrated)

-

-

Over-all length of 43.5 inches;

-

blade length 31.6 inches;

-

the mounts are

undecorated gilt copper, very rich feeling;

-

lozenge shaped tsuba with round

and slightly raised edge;

-

haft secured by three heavy rivets;

-

the blade is

wide, long, heavy, and typically straight and single edged.

-

-

Over-all length of 34.6 inches;

-

blade length 25.5 inches;

-

the mounts are of gilt copper, the haft decorated

with a repousse wave pattern;

-

pommel typically bulbous and set obliquely;

-

tsuba of unperforated hoju form, very thin with round

raised edge;

-

haft secured by two rivets;

-

the blade is straight and single edged.

-

This form is the 'mallet-headed' sword mentioned in

ancient literature.

-

-

Over-all length of 31 inches;

-

blade length 23.9 inches;

-

the mounts of gilt copper; haft decorated with bosses

in repousse;

-

pommel enclosing the head of a phoenix holding a

jewel;

-

tsuba is of hoju shape with six trapezoidal openings,

very thin with raised edge;

-

haft is apparently secured by jamming;

-

the blade is

straight and single edged.

-

This form of mounting is traditionally supposed to

have been derived from Korean models. The impression is of dainty

functional elegance.

-

HOJU TSUBA (not illustrated) Circa 6th century A.D. Iron,

much incrusted; hoju form with eight trapezoidal openings; width 3.1 inches;

length 3.5 inches; thickness at edge .25 inches, at center .12 inches.

The formalizing of the shape and style of the Japanese

sword which occurred during the early tenth century was followed by the

emergence of the first schools, prominent among which were the Sanjo and

Gojo of Yamashiro, the Mogusa of Mutsu, the Ohara of Hoki, the Naminohira of

Satsuma, and the Ko-Bizen smiths. A certain ambivalence of style is very

noticeable. There are the slender and exceedingly graceful blades that seem

well suited to the court which may be contrasted with the heavier and more

manly blades which smell of the battlefield. Towards the end of the era the

Genpei wars between the Taira and the Minamoto clans created a demand for

weapons which caused the appearance of more schools and stimulated the

advancement of the art. Swords made before the advent of the Kamakura period

(1185 A.D.) were made principally by the Yamashiro method, although the

Yamato was the first in order of historical appearance.

-

-

-

-

-

Hamon is hoso suguba with some nijuba;

-

Jihada is masame with yubashiri and some ji-nie,

texture of the steel is very fine;

-

-

Comments: Traditionally, the earliest signatures

found on swords is the legendary 'Amakuni of Yamato.' His blades are

made in the earliest of five methods to appear historically, the Yamato.

Accompanying letter by Honami Koson.

-

Signed Bizen Kuni Tomonari saku.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, wide and powerful blade, koshi

zori;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-midare of nie, profuse small

bright kinsuji in the ha-buchi, sunagashi, nie saki, strong activity in

the ha;

-

Jihada is mokume itame mixed, some o-hada, ara nie

in ha-buchi;

-

Jitetsu is zanguri, very homogeneous and beautiful;

-

Boshi is maru with some nijuba, a characteristic of

Tomonari;

-

Nakago is suriage, signature strong and excellent;

-

Comments: This blade is made in the Yamashiro

tradition, the second of five methods to appear historically. Ko-Bizen

Tomonari is one of the greatest smiths in all of sword history.

Accompanying origami by Honami Koju dated 1714. A masterpiece.

-

Signed Bizen Kuni Kanehira saku.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri koshi zori with utsumuku,

ko-kissaki;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-midare of nie, inazuma, ha-hada,

some sunagashi, strong activity;

-

Jihada is itame mokume mixed, o-hada;

-

-

-

Comments: One of the famous ko-Bizen triumvirate,

Kanehira, Sukehira, and Takahira, called the Sampira, or the Three Hira.

This is a most important blade of National Treasure class. It is

accompanied by an Honami origami dated 1780 and a certificate with the

signature and seal of the Tokugawa Shogun.

-

Signed Masatsune, cut out and inlayed (gaku mei).

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, slender with beautiful

curvature;

-

Hamon is hoso suguba of nie, sprays of nie in the ha-buchi,

slight irregularities;

-

Jihada is mokume itame mixed, ji-nie, very fine skin;

-

Boshi is maru, ko-kissaki;

-

-

Comments: This blade is a classic example of early

slender tachi form by a first class ko-Bizen smith. It is accompanied by

a document with the signature and seal of the 11th Tokugawa Shogun

Ienari dated 1792 presenting the sword to Lord Mizuno and a document by

Lord Mizuno describing the presentation.

-

Signed Bungo Kuni no ju Yamanaka Yukihira saku.

-

Date 1057 (the usual date given for this smith is

1171);

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, strong koshi zori, ko-kissaki,

utsumuku;

-

Hamon is suguha ko-midare of nie, kinsuji, inazuma;

-

-

Jitetsu is fine and dense, slight utsuri, few ji-nie;

-

-

Nakago is ubu with strong sori;

-

Comments: Typical elegant, beautiful Heian form. Made

in the Yamashiro tradition.

During the early part of the thirteenth century the

ex-Emperor Go-Toba called the most prominent smiths in the country to Kyoto to

work with him in the fashioning of swords. This unheard-of distinction initiated

a golden era in sword history which lasted for approximately one hundred years.

Never again was this zenith to be approached. The Shogun Yoritomo founded his

camp-capitol at Kamakura, a small fishing village, in order to avoid the

debilitating decadence of the court and set a fashion simple and manly. Even the

court aped this mood. Two of the traditional five methods made their first

appearance during this era. The Bizen method, founded during the early years by

the ban-kaji Norimune and the Soshu method, which was founded during the latter

part of the period by the Yamashiro Awataguchi smith Shintogo Kunimitsu who was

followed by Yukimitsu and the great Masamune. Shifting centers of power caused

the migration of smiths to new sources of patronage and many new families of

smiths appeared. During the closing years, the wars between the followers of

Ashikaga Takauji and the adherents of the Emperor Go-Daigo, whose headquarters

were at Yoshino in the province of Yamato, caused the resuscitation of the

practically defunct Yamato method. The great majority of swords now classed as

national treasures or important art objects were made during the Kamakura

period.

-

-

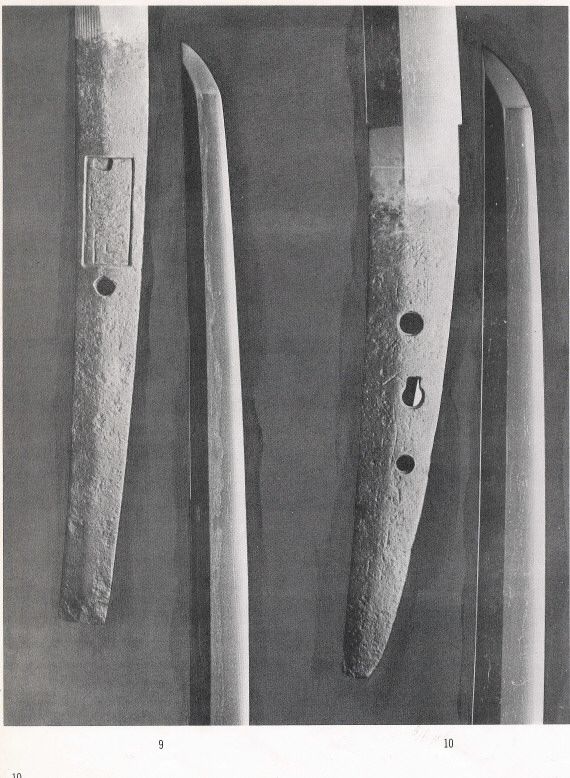

Date late Heian to early Kamakura;

-

-

Shape ken form with thick diamond shaped cross

section;

-

Hamon is hoso suguba of nie;

-

Jihada is ko-itame with no-nie;

-

Jitetsu is fine and dense;

-

-

Comments: Hisakuni was probably the most important of

the smiths chosen by the Emperor Go-Toba (ban kaji). A member of the

Awataguchi family who worked in the Yamashiro tradition. Accompanying

letter by Honami Koson.

-

Signed Sukehide, with 17 petal chrysanthemum.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri with strong sori, high shinogi,

fumbari;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-midare of mixed nie and nioi, ashi,

kinsuji;

-

Jihada is mokume with some o-hada, yubashiri, ji-nie

is typically fine and dense;

-

Boshi is hakkake with kaeri;

-

Nakago is slightly suriage;

-

Comments: Sukehide was the name used by the

ex-Emperor Go-Toba while in exile on the island of Oki. He was

accompanied in exile by six smiths who were called the Oki no Ban Kaji.

Swords with his signature are exceedingly rare..

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori, fumbari, strongly

curved;

-

Hamon is ko choji midare with kawazuko choji, profuse

nie at the ha-buchi, ashi, yo, kinsuji;

-

Jihada is itame mokume mixed, zanguri;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Only one other signed blade by this smith

is in existence, the national treasure 'Kurumbo Kiri' of the Date

family. The form may be taken as definitive in its beauty. Kagehide was

the younger brother of Mitsutada, founder of the early Osafune school of

Bizen.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, tori zori;

-

Hamon is suguba with one area on the omote side below

the mono-uchi of ko-midare, ha-buchi is mide with clear and luminous

ko-nie, some nijuba;

-

Jihada is ko-itame, almost no ji-nie;

-

-

-

-

-

Comments: Awataguchi Norikuni of Yamashiro was one of

the Emperor Go-Toba's selected smiths and an Oki no Ban Kaji. The son of

Kunitomo.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, tori zori, slight fumbari;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-choji midare of ko-nie in nioi,

ha-buchi is wide and brilliant, few ashi;

-

Jihada is mokume itame mixed, utsuri;

-

-

-

-

-

Comments: Noritsugu was one of the Emperor Go-Toba's

chosen smiths.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori;

-

Hamon is juka choji, very deep and extremely

flamboyant, mainly nioi with sparse ko-nie and kinsuji, deep ashi and yo;

-

Jihada is itame with no ji nie, strong utsuri;

-

-

-

Comments: This is a very good and characteristic

example of the developed Fukuoka Ichimonji style. The founder of the

school is said to have been Norimune of Bizen, one of the Emperor Go-Toba's

smiths. The primary smiths of this school did not use their name only.

Followers signed using the character 'Ichi' meaning first. This blade

was an heirloom of the Aoyama family.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri of beautiful form, tori zori;

-

Hamon is midare and gunome midare of nie in nioi,

profuse kinsuji and inazuma;

-

Jihada is mokume and itame mixed, the mokume being

particularly noticeable, ohada, chikei, zanguri, hada is very prominent;

-

Boshi is midare komi, yakizumi;

-

Nakago is suriage, the color of the patina is

superlative;

-

Comments: Nagamitsu was one of the greatest of the

early Osafune smiths and his works are represented in the list of

national treasures. Later in life he signed using the name Junkei. This

sword, hereditary in the Tsuchiya family, is a most excellent example of

his work. Accompanying authentication by Honami Koson.

-

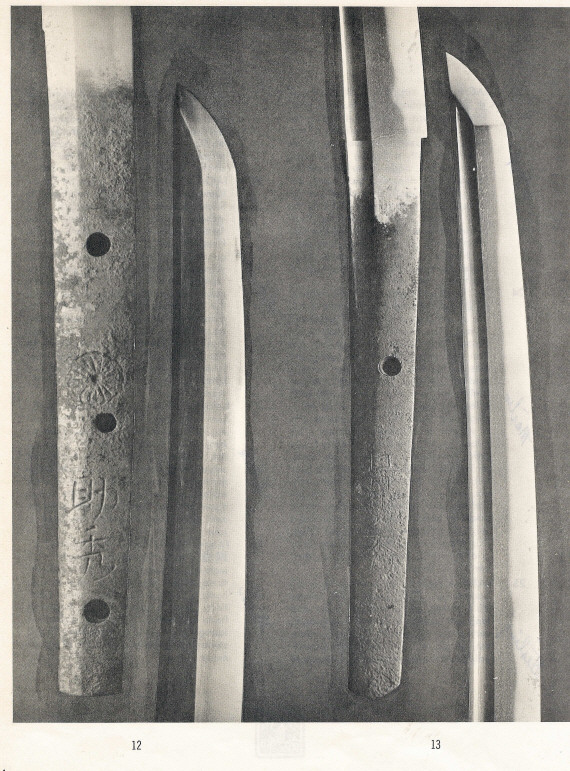

Signed Senjuin and Uesugi Terutora shoji.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, tori zori;

-

Hamon is hoso suguba with slight irregularities,

hotsure, wide ha-buchi of ko-nie, kinsuji;

-

Jihada is a running itame, slight utsuri;

-

-

-

Nakago is suriage with Uesugi Terutora shoji cut out

and folded over (orikaeshi);

-

Comments: This inscription, added later, indicates

that the sword belonged to the famous Uesugi Kenshin of Echigo. The

Senjuin worked in the Yamato tradition and used the name of the temple

as their only signature.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori, fumbari;

-

Hamon is suguba of ko-nie, nijuba in the mono-uchi,

hotsure, uchinoke;

-

Jihada is running ko-itame;

-

Jitetsu is extremely fine;

-

-

-

Comments: Tegai Kanenaga, one of the most famous of

the late Kamakura Yamato smiths, was a man of older style than his

contemporaries. This sword has a sayagaki dated 1745 which states that

it was made a gift from the imperial palace on that date.

-

-

-

-

-

Hamon is suguha of nie, very fine kinsuji and inazuma;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume with some o-hada;

-

Jitetsu is very fine and the color is dark;

-

-

-

Comments: Good and typical Yamashiro den of the

period.

-

Unsigned, attributed to the Rai school.

-

-

-

Shape u-no kubi zukuri of classic form;

-

Hamon hoso-suguba of ko-nie, sunagashi, kinsuji;

-

Jihada is ko-itame ko-mokume mixed;

-

Jitetsu is extremely fine with small ji-nie;

-

Nakago is slightly suriage;

-

Comments: This is a typical Yamashiro blade of very

high quality.

-

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri take-no-ko zori;

-

Hamon is gunome midare of nie, kinsuji, inazuma;

-

Nashiji hada, profuse ji-nie;

-

-

Boshi is ko-maru with long kaeri;

-

Hori on omote is lotus and jewel, ura kaeri;

-

-

Comments: Kunihiro was the son of Shinto Kunimitsu,

progenitor of the Soshu tradition, and may have succeeded to his

father's name. His work is rare.

-

Signed Masamune in gold, authenticated by Honami Kojo.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is o-midare of nie, sunagashi, inazuma, profuse

nie;

-

Jihada is o-itame with a feeling of ayasugi, profuse

ji nie, hada is very prominent;

-

Jitetsu is very clear and translucent;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Masamune is probably the most famous of all

swordsmiths. Most blades made by him have been shortened, losing the

signature. Only three signed blades by him are known to exist. Under his

leadership the Soshu method became clearly established.

-

Signed Norishige in gold, authenticated by Honami

Koyu, ura a rectangular gold plug engraved 'Fubuki' (Snowstorm).

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, tori zori;

-

Hamon is midare of nie, sunagashi, kinsuji, inazuma,

some ara nie;

-

Jitetsu is medium density, well forged, strong

feeling;

-

-

Futatsu ji-bi on both sides

-

-

Comments: Etchu Norishige, with Goro Niudo Masamune,

was a student of Shintogo Kunimitsu. This sword is a good example of

early Soshu style. Accompanying origami by Honami Tadaaki, kofuda by

Honami Shichirobei, Honami Saburobei, and three others, accompanying

letters by Honami Tadaaki and Honami Tadamasa, and a poem by Saito Soho,

Lord of Nishikawa Jiri, Omi province, written about 1558. This sword was

an heirloom in the family of Kyogoku, Lord of Sanuki, a member of the

Sasaki family.

-

Signed Sagami Kuni no ju nin Sadamune.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, wide and long with o-kissaki;

-

Hamon is o-midare, very deep, sunagashi, tobiyaki,

inazuma;

-

Jihada is itame, yubashiri (rounded);

-

-

Hori on omote is renge, gomabashi-bi, and bonji, ura

is Tsumetsuki-ken, and bonji

-

Nakago is ubu of tanago bara form;

-

Comments: Sadamune is believed to have been the

adopted son of Masamune and, after the master, is probably the most

famous of the Soshu smiths. Signed work is extremely rare.

-

Attributed to Shizu Saburo Kaneuji, sword is named in

gold 'Sasa no Tsuyu' (Dew on the Grass) .

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, typical Soshu form;

-

Hamon is notare midare of nie, kinsuji, inazuma, ashi,

some feeling of gunome;

-

Jihada itame mokume mixed, yubashiri;

-

Jitetsu is very clear and damp feeling;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Kaneuji was one of the Masamune ju-tetsu or

ten rival students of Masamune. He originally came from Yamato and after

his study with Masamune migrated to Mino where he founded the fifth of

the five traditional schools (Gokkaden). An excellent and beautiful

sword, very typical of his work.

-

-

-

-

-

Hamon is suguba gunome choji of nie, sunagashi,

kinsuji, inazuma, ashi, hotsure;

-

Jihada is o-mokume with some itame, chikei;

-

Hori on omote is gomabashi-bi, ura is koshi-bi and

soye-bi ;

-

-

Comments: One of the Masamune ju-tetsu. Later

migrated to Mino and established a school. His work is rare.

-

Signed Soshu no ju Tsunamitsu.

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, chukan zori sunnobi tanto;

-

Hamon is suguba of nie in nioi;

-

Jihada is itame, ji-nie, chikei, hada is distinct;

-

-

-

Bo0hi and soye-bi on both sides

-

-

Comments: Said to have been first a student of

Yukimitsu and later of Masamune.

Return to the Table of Contents

The schism between the Ashikaga Shogun, Takauji, and the

Emperor Go-Daigo resulted in the flight of Go-Daigo to Yoshino in Yamato and

the establishment of a new Emperor in Kyoto. The period is sometimes called

the 'Nan-Boku Cho Jidai' or the 'Age of the North and South Courts.' It was

an era of heroes and scoundrels, of the proto-typical loyal samurai Kusunoki

Masashige and Nitta Yoshisada and the proficient but brutal and treacherous

brothers Ko. It was an age of incessant warfare and battles. The great

demand for weapons naturally caused a general deterioration of quality in

the sword, although master-smiths continued to produce work of the highest

quality. Of particular note were the migrations of smiths to the province of

Mino and the establishment of the last of the Gokkaden. The most important

were Kaneuji and Kinju of Soshu (Masamune ju-tetsu) and a numerous group of

Yamato smiths including Zenjo Kaneyoshi. Another important center which

continued an ancient tradition was at Osafune in Bizen. These two provinces

produced the major portion of the swords made in Japan.

-

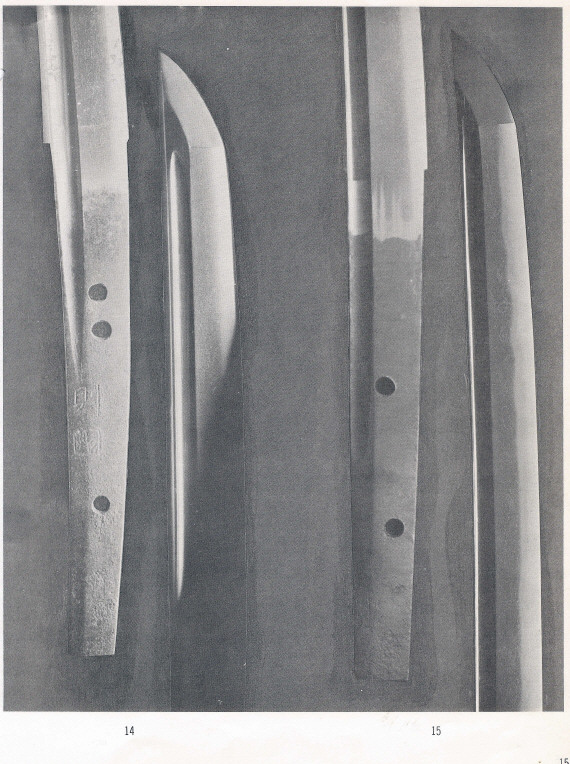

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri ko wakizashi, wide and very thin,

Enbun-Joji shape;

-

Hamon is ko-midare of ko-nie in nioi, ha-buchi is

indistinct and watery (urumu), small kinsuji;

-

Jihada is o-mokume and itame mixed;

-

-

Boshi on the omote is su-ken with bonji, ura is

gomabashi-bi;

-

-

Comments: Hasebe Kuninobu was the son of Hasebe

Kunishige, one of the ten students of Masamune. He also used the name

Kunishige.

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, fumbari, slender delicate shape;

-

Hamon is hoso suguba of ko-nie, hotsure, kinsuji;

-

-

-

-

Nakago is suriage with signature retained and folded

over (orikaeshi mei);

-

Comments: The Kaneyoshi were students of the Tegai of

Yamato who later migrated to Mino and founded their own school.

Originally this was a ko-dachi which was shortened and made into a

wakizashi.

-

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, chukan zori, Enbun-Joji shape;

-

Hamon is hoso suguba of ko-nie, slight hotsure;

-

-

Jitetsu is very fine and beautifully worked;

-

Boshi is o-maru, slightly kareru;

-

Hori on omote is ken and bonji, ura is ken and bonji

in hi (ukibori)

-

-

Comments: The first Nobukuni was a student of

Sadamune of Soshu who later migrated to Kyoto and established his own

famous school there. The Nobukuni were famous as carvers of horimono.

-

Unsigned, attributed to Soshu Hiromitsu .

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri of Enbun-Joji style;

-

Hamon is suguba of ko-nie, nijuba, yo;

-

Jihada is a little open and has a feeling of wetness;

-

Jitetsu is fine and well forged, the hada is sinking;

-

Boshi is ko-maru with slight kaeri;

-

Nakago is ubu, tanago bara form;

-

Comments: Hiromitsu was a son or student of Sadamune

of Soshu. The attribution is by Shimizu Toro.

-

-

-

-

-

Hamon is midare of nie, togare, kinsuji;

-

Hada is mokume with some itame mixed, utsuri;

-

Jitetsu is of medium density, a little open;

-

Boshi is midare komi with some hakkake;

-

-

Comments: The first Tomoshige of Kaga was a student

of Rai Kunitoshi of Yamashiro. The work of the school; however, contains

the elements of the styles of Mino, Bizen, and Soshu and is classified

as wakimono (outside the main lines of school styles). This sword

exhibits some tendency toward the koshi hiraita midare hamon (open hip,

with valleys) which became popular during the Oei period.

-

Signed Bizen Osafune Tomomitsu.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori;

-

Hamon is gunome midare of nie, kinsuji, inazuma,

sunagashi, nie saki, some hotsure;

-

Jihada is itame mokume mixed, profuse chikei;

-

Boshi is midare komi, yakizumi;

-

Bo-hi with bonji on both sides

-

-

Comments: Tomomitsu was the son or brother of the

famous O-Kanemitsu of Bizen, one of the ten students of Masamune. This

blade has definite overtones of the Soshu style which are probably due

to this relationship. The style is called Soden Bizen.

-

Signed Naoe Kanehisa, in gold, authenticated by

Honami Koson.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, strong koshi zori;

-

Hamon is suguba with center section of blade in

gunome choji of nie, kinsuji, sunagashi;

-

Jihada is mokume and itame mixed;

-

-

-

Comments: Kanehisa was the son of Kanetoshi, younger

brother of Shizu Saburo Kaneuji (Masamune's student). This blade is of

an older form and the hamon is unusual and interesting.

-

Signed Hiromasa, in gold, authenticated by Honami

Koson.

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri ko-wakizashi;

-

Hamon is o-midare of nie, ara nie, ashi, yo;

-

Jihada is masame, ji-nie becoming dense toward the

point;

-

Boshi is togare with long kaeri;

-

Hori on omote is kuichigai-bi, ura is su-ken with

jewel (tama)

-

-

Comments: Hiromasa was a man of the late Soshu

tradition. Many of the earlier characteristics were changing and in some

cases disappear entirely. The masame hada is a striking deviation from

the norm.

Return to the Table of Contents

With the reconciliation of the two imperial houses and

the re-unification of Japan, the Nan-Boku Cho came to an end. Political

power continued to be vested in the Ashikaga Shoguns, but the inherent

weakness of the system prevented the establishment of political unity. Petty

warlords seized local power and the slight control exercised by the Ashikaga

diminished until the Onin period (1467) when the country again exploded into

civil war. The next one hundred years is known as the 'Sengoku Jidai' (Age

of the Country at War). During this century, the country was utterly

devastated and reduced to poverty. Kyoto, the ancient capital, was burned,

an irretrievable loss. There are relatively few schools producing good work

during the Muromachi period. The majority are kazuuchi mono (ready made) or

were even mass produced. As always, however, some conscientious smiths

continued to follow a tradition of excellence.

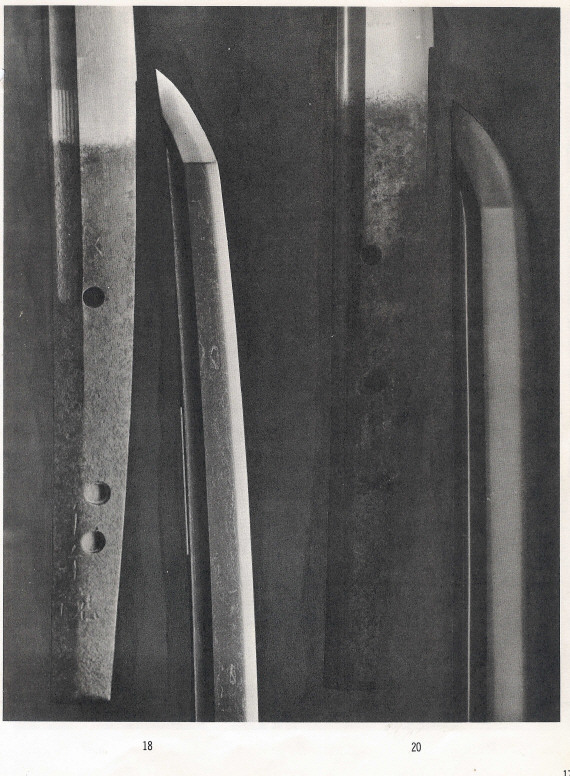

-

-

-

-

Shape shobu zukuri, very wide and long;

-

Hamon o-midare hamon of ko-nie in nioi;

-

-

Jitetsu has a feeling of softness and is clear;

-

Boshi is hakkake with long kaeri;

-

Hori on omote is Fudo and stylized cloud with bo-hi,

ura is dragon with bo-hi;

-

Nakago is ubu of typical tanago bara form;

-

Comments: Muramasa blades excite a great deal of

interest because of the numberless stories concerning their

bloodthirstiness. They were supposed to have been particularly unlucky

for the Tokugawa. Shirai Gompachi, the street killer, is said to have

used a Muramasa blade. There were several smiths of the same name who

followed the Mino tradition at Sengo in the province of Ise..

-

WAKIZASHI (not illustrated)

-

Signed Norimitsu, in gold.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, fumbari;

-

Hamon suguba of ko-nie, hotsure, no activity in the

ha;

-

Jihada o-mokume, few ji-nie;

-

Jitetsu open but not coarse;

-

-

-

Comments: An early example of the Norimitsu line who

worked at Osafune in Bizen. There were many smiths who used the name,

some of very good quality. They were swords for practical use. This

sword is of chu-mon uchi (special order) quality.

-

Signed Bishu Osafune no ju Norimitsu.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori, strong fumbari;

-

Hamon choji midare of nie, kinsuji, inazuma, ha-hada;

-

Jihada is mokume, yubashiri, profuse ji nie, hada is

strongly marked, the pattern outlined with bright silvery lines;

-

-

-

Comments: There were seven smiths of this line, the

second and third being the most important. This sword is most probably

by the third.

-

Signed Bizen Osafune Katsumitsu.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, strong sori;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-midare of nie hotsure, kinsuji;

-

Jihada is mixed itame mokume;

-

-

Boshi is midare komi (Bizen boshi) with hakkake;

-

-

Comments: Typical mid-Muromachi blade of the

later Bizen mode with its roots in the style of Oei Bizen. There is

nothing extreme and it may be called 'koroai' or 'just right.' A sword

for practical use.

-

Signed Bizen Kuni no ju Osafune Yosozaemon no Jo

Sukesada.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is suguba of nie, sunagashi, inazuma, kinsuji,

hotsure;

-

Jihada is ko-itame, slight utsuri;

-

Jitetsu is dark and the yakiba very luminous;

-

-

Comments: There are forty one smiths of the Sukesada

line recorded - and many more unrecorded. The first Yosozaemon is one of

the most important of this line. The date on this blade is correct for

the first.

-

Signed Bingo Mihara no ju Masachika.

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, take-no-ko-zori;

-

Hamon is suguba ko-midare, ko-ashi, yo, nie are

coarse and brilliant, wide ha-buchi;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume, approaching nashiji, ji-nie,

yubashiri;

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori;

-

Hamon is suguba of nie in nioi, fushi nie in the

ha-buchi are very brilliant;

-

Jihada is very subtle ko-mokume;

-

-

-

-

Comments: One of the early Kanesada of Mino, the

first two smiths being the most important. An excellent blade with a

firm and strong shape.

-

Signed Bishu Osafune Sukesada saku.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori, strong fumbari;

-

Hamon is choji midare with valleys of nioi, some

formed like crab claws, typical Bizen togare tipped with nioi, koshi

hiraita midare (open hipped);

-

-

Jitetsu is soft feeling and fine;

-

-

Nakago is ubu of Bizen form;

-

Comments: This is a classic example of the

mid-Muromachi blade of the Sukesada school made for practical use.

-

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, slight sori;

-

Hamon is gunome choji of nie, sunagashi, small

kinsuji, ha-hada;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume which is very prominent and which

may be used as an exact example of mokume;

-

Jitetsu is bluish, somewhat open texture;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Hirosuke is a smith of the Shimada school

of Suruga.

-

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, slight sori;

-

Hamon is o-gunome, profuse nie in the area of the

ha-buchi which is wide and brilliant;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume becoming masa close to the mune;

-

Jitetsu is fine and very clear;

-

Boshi is ko-maru (Mishina boshi);

-

Gomabashi-hi on omote, ura bo-hi;

-

-

Comments: Kanemichi was the founder of the prolific

Mishina school of Mino which migrated to many parts of Japan during the

succeeding period. Their blades are very numerous in western collections

because of their rather obvious attractive qualities.

-

Signed Bizen Kuni no ju Osafune Shichibei no ju

Sukesada.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, koshi zori;

-

Hamon is midare mainly nie, ashi, yo, sunagashi, same

ara nie;

-

Jihada is primarily mokume;

-

Jitetsu well forged with prominent hada;

-

-

Nakago is ubu, Bizen form;

-

Comments: One of the better smiths of the Sukesada

school. Chu-mon uchi (special order).

Return to the Table of Contents

Shinto and Shin-Shinto

Although the true Edo period comes a little later, Keicho is

taken as the date separating Koto (Old Swords) from Shinto (New Swords). Before

Keicho, swords were made in the traditional style of the place where the smith

worked. After 1596 the relocation of the Daimyo and the movement of their vassal

smiths with them makes the identification of place by method extremely

difficult. Additionally, the use for the first time of factory steels causes

swords made using them to look alike and to lose their distinctive identity.

Traditional methods were violated and the swords of the Shinto Tokuden have fine

grain, wide hamon, and ara nie. They are brittle and will break.

As was so often true, the period began with a tremendous

surge of inspired creativity. A large number of talented smiths studied with the

great metal worker Umetada Mioji at Nishijin in Kyoto and with his co-worker

Kunihiro at Ichijo Horikawa. Most of the great master smiths of the Edo period

were derived from this school.

Inspired largely by the efforts of Suishinshi Masahide, we

find at the beginning of the 19th century a movement to return to the early

traditional methods and shapes. Unfortunately, the models chosen were many times

early, shortened examples. The shape, therefore, leaves something to be desired.

Several outstanding smiths came out of the Suishinshi school. these swords are

called 'Shin-Shinto' or "Newer-New Swords.'

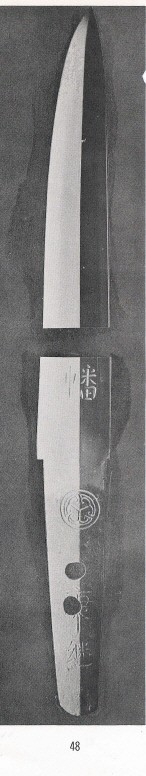

-

Signed Yasutsugu, on ura 'while residing in Edo,'

with the Tokugawa mon.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is suguba with wide ha-buchi of nie;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume, almost nashiji;

-

Hori on omote 'Hachiman' ;

-

-

Comments: The first Yasutsugu was swordsmith to the

Tokugawa Shogun, Ieyasu, and was accorded the honor of inscribing the

Tokugawa mon on his work. His descendants continued this practice. Much

of his work was decorated by the famous carver, Kinai of Echizen. He was

the first to use foreign steel.

-

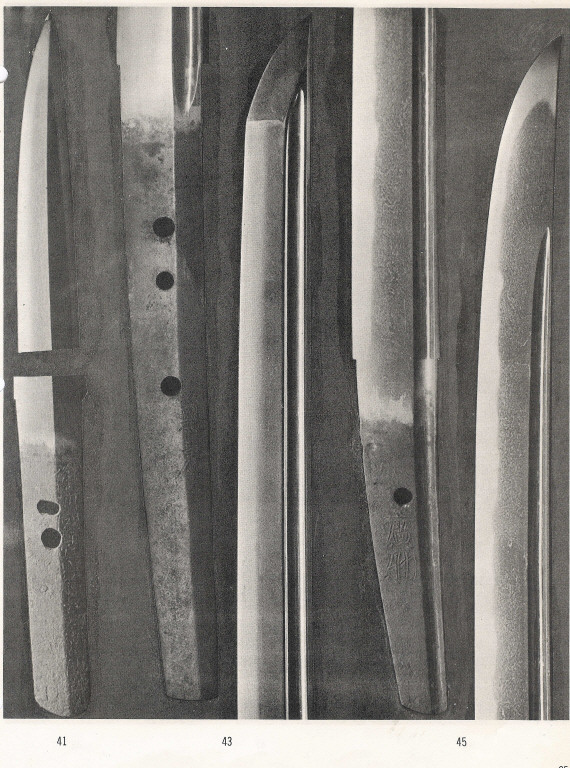

Signed Hizen Kuni no ju nin Hironori. Recorded on the

ura is a test dated 1662 in which two bodies were cut by the famous

tester Yamano Kauemon no Jo Nagahisa.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, tori zori;

-

Hamon is o-choji midare of nie in nioi, kinsuji,

inazuma, sunagashi, ashi;

-

Jihada is ko-itame, ji-nie;

-

Boshi is midare komi (Bizen boshi);

-

-

Comments: Hironori was a student of the first

Tadayoshi of Hizen who was a student of Umetada Mioju. The name

Nagahisa, the tester appears on many of the famous early Shinto blades.

-

WAKIZASHI (not illustrated)

-

Signed Tsuda Echizen no Kami Sukehiro.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is toran of nie, somewhat hotsure, small

kinsuji, nie saki;

-

Jihada is nashiji, ji nie;

-

Jitetsu is very fine and homogeneous;

-

-

-

Comments: Typical Shinto Tokuden. Sukehiro was noted

for his beautiful toran ba, the conception of which was the product of

his own creativity. One of the most famous of Shinto smiths.

-

Signed Yamato no Kami Yasusada.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, heavy and wide;

-

Hamon is hiro suguba, wide ha-buchi of ko-nie,

ko-ashi;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume - almost nashiji, ji-nie;

-

Boshi is o-maru with long kaeri;

-

Bo-hi on both sides, ato bori (put in later)

-

-

Comments: A smith of the Edo school of Musashi.

Typical Shinto Tokuden.

-

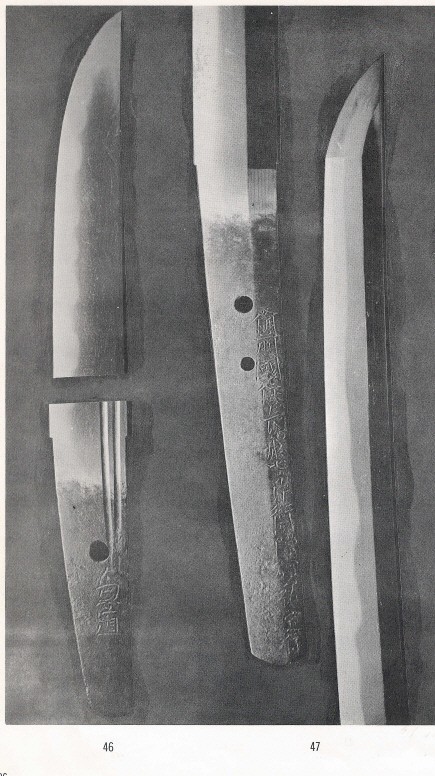

Signed Hizen Kuni no ju Mutsu no Kami Tadayoshi.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is chu-suguba, wide ha-buchi of ko-nie, very

brilliant;

-

Jihada is nashiji, very fine and dense;

-

-

-

Comments: This blade is by the third Tadayoshi and is

a definitive example of his work.

-

Signed Inoue Izumi no Kami Kunisada.

-

Date 1671, with chrysanthemum;

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, slight sori;

-

Hamon is notare gunome choji, profuse nie in the

ha-buchi;

-

Jihada is nashiji, ji-nie;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Typical Osaka yakidashi (straightening of

the hamon at the nakago). Kunisada was the name used by Inoue Shinkai

prior to 1672. This blade is typical of the Osaka style.

-

-

Date 1678, with chrysanthemum;

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, shallow sori;

-

Hamon is notare, wide ha-buchi of nie, inazuma, Osaka

yakidashi;

-

-

-

-

Comments: This blade is comparable to others by this

famous smith.

-

Signed Awataguchi Omi no Kami Tadatsuna.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is hitatsura yaki of nie and nioi, Osaka

yakidashi, nie saki, sunagashi;

-

Jihada is itame with masame in the shinogi ji;

-

Boshi is o-maru (Osaka boshi);

-

-

Comments: This blade is by the first Tadatsuna of

Osaka, progenitor of a highly regarded line who were especially notable

for their carving. The hamon of hitatsura is not normal to this smith's

style.

-

WAKIZASHI (not illustrated)

-

Signed Awataguchi Omi no Kami Tadatsuna.

-

-

-

Shape is hira zukuri, wide and heavy with slight sori;

-

Hamon is chu-suguba of nie;

-

-

Jitetsu is typical Shinto;

-

-

Hori on omote is a dragon, ura is a ken, the carving

is strong

-

-

Comments: Tadatsuna the second was famous for his

carving of horimono as well as his skill as a smith. The hamon is out of

style for the smith.

-

Signed Echigo no Kami Kanesada.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is o-choji midare - close to toran, nie in nioi;

-

Jihada is almost nashiji of excellent color;

-

-

-

Comments: Sakakura school of Settsu. Alternative name

used by Terukane, the second Kanesada. The line is derived from the

Hidari Mutsu school.

-

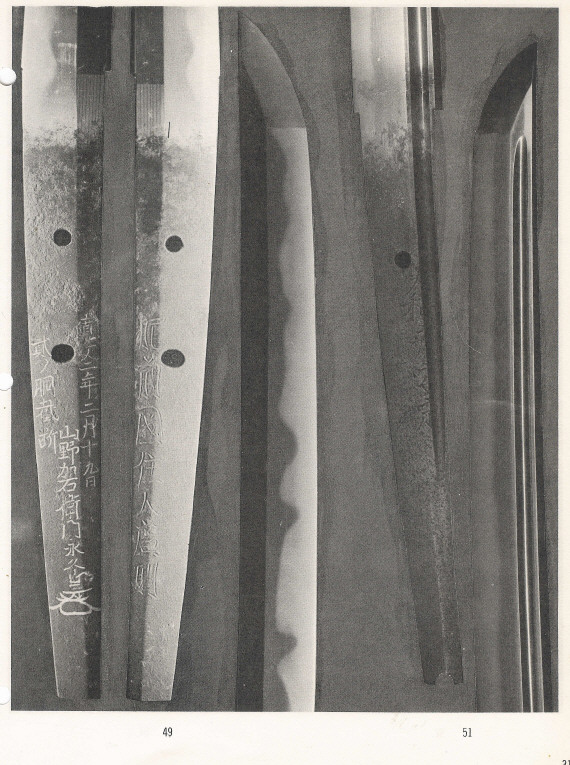

Signed Bungo Yukihira sue Takada Kawachi no Kami

Motoyuki shichi ju ichi sai saku.

-

-

-

-

Hamon is o-midare of nie with ara nie, nie saki;

-

Jihada is o-itame, very prominent;

-

-

-

-

Comments: Originally of the ancient Bungo Takada

school, became a member of the Later Tadayoshi school of Hizen.

-

Signed Oku Yamato no Kami Taira no Ason Motohira.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, almost osoraku zukuri with very

long kissaki, wide and heavy;

-

Hamon is notare midare, ara nie, sunagashi, kinsuji;

-

Jihada is o-itame, coarse ji nie;

-

-

Hori on ura is gomabashi hi with renge

-

-

Comments: Recent Satsuma school whose origins were

founded in Yamato. He excelled in making swords in Soshu style.

-

Signed Masahide, with kakihan and stamped seal.

-

-

-

Shape hira zukuri, Enbun-Joji shape;

-

Hamon is suguba of nioi with ko-nie in the ha-buchi;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume, damp feeling and translucent;

-

-

Hori on omote 'Hachiman dai Bosatsu,' ura 'Namu Myoho

Renge Kyo';

-

-

Comments: Suishinshi Masahide was the inspiration for

the renaissance in the art of the swordsmith which occurred about 1804.

He advocated a return to the traditional methods and shapes of the

earlier great periods. His influence was widely felt.

-

Signed Daijoka no ju Koyama Bizen no Suke Munetsugu

and So-Ichiro Munetsugu Saijin kore.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, wide and heavy;

-

Hamon is ko-choji midare, some juka choji, inazuma,

kinsuji;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume with many ji-nie and chikei;

-

Boshi is o-maru with small kaeri;

-

-

Comments: Kato school of Musashi, signed by both the

first and second Munetsugu. The first was a student of Tsunateru of Dewa.

-

Signed Keio gannen hachi gatsu hi Fujiwara Kiyondo,

on ura Akita Innai tame Saito Ujichika kitau kore.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri, slight sori;

-

Hamon is notare gunome choji, ashi, inazuma, chikei;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume in masa (very pale striations),

ji -nie;

-

Boshi is ko-maru with streamers of nie;

-

-

Comments: Kiyondo was a student of Kiyomaro, founder

of the Yamaura school of Edo. Many of their blades resemble the style of

Shizu.

-

Signed Gassan Sadakazu kinsei no kitai, tei shitsu

gigei in, with kakihan.

-

-

-

Shape shinogi zukuri of beautiful curve;

-

Hamon is juka choji with deep ashi and yo, mainly

nioi with ko-nie;

-

Jihada is ko-mokume with slight utsuri, very fine ji

nie;

-

-

-

-

Comments: This blade was made by special appointment

for the Emperor Meiji and is a masterpiece. Sadakazu was famous for his

ability to duplicate the work of earlier masters and his carving of

horimono was unrivalled in any age. This sword is in the style of Bizen.

-

Signed Bizen Kuni Osafune no ju Toshimitsu.

-

Made in 1961 for Robert Haynes;

-

-

Shape is hira zukuri chukan zori of excellent form;

-

Hamon is midare, mainly nie, sunagashi, kinsuji,

strong activity in the ha-buchi;

-

Jihada is running ko-itame;

-

Jitetsu is very clear and deep;

-

Boshi is ko-maru with hakkake;

-

-

Comments: Toshimitsu is the last smith living in

Osafune, working there for love of the art. this blade is a most

beautiful example of his work.

Return to the Table of Contents

The fittings for the Japanese sword were designed for both

functional and aesthetic purposes. The artist value of these fittings has

survived not only the edict prohibiting the wearing of the sword, but the

passing of the artists as well. In spite of this disappearance of the artisans,

their contributions to the beauty of the mounted sword have become a distinct

art form. This form has gained popularity in the western hemisphere - possibly

because of the numerous facets which comprise the various mountings.

There are techniques and skills to satisfy the most exacting

connoisseur as well as striking colors and designs to intrigue event the casual

observer.

The fittings may be enjoyed on several levels. Some

collectors acquire pieces for the obvious visual beauty of the decoration.

Others collect as many various types or as many of a single type as possible.

Those who go more deeply into the subject may be strongly influenced by the

arbiters and judges of fashion in Japan and will at first adhere to their

dictates, later he may follow his own path. What ever way the student chooses,

the enjoyment and study within this field will offer both satisfaction and a

challenge seldom to be found in any other.

This exhibit is primarily intended to illustrate the

chronological development of the sword and its fittings. Since examples of tsuba

prior to 1400 are very rare, even in museums and shrines in Japan, we are

primarily confined to the 500 year span from 1400 to 1900.

Particular attention has been paid to the selection of

examples which are typical of individual schools and the eras in which they

enjoyed their greatest success. The styles of design and execution are sharply

defined in many instances; but the influence of one school on another or a

then-current fashion for particular subjects or techniques has provided the

students and the experts with endless opinions and grounds for forming them.

All descriptions, datings and information in this catalogue

are based on an exhaustive review of the literature on the subject. This

research is further amplified by individual contributions from those who have

made lifetime studies in the areas represented in this collection.

It will be noted that some pieces in the tsuba section have

the annotation that they are certified pieces. This means that these pieces have

been examined by one of the experts in Japan and they have passed judgment on

the authenticity and quality of the piece. These certificates are written on the

inside of the box lid in which the pieces are stored. The experts who have

written these certificates mentioned in this exhibit are:

-

Kuwabara Yojiro, one of the leading experts in the early

part of this century.

-

Ogura Soemon (Amiya Soe), author, dealer, and prime

source of fine tsuba in the same period.

-

Torigoye Kazutaro (Kodo), author of many works on both

the blade and the tsuba, now living in Okayama city. He is today the leading

expert in the field of tsuba and is the mentor of the growing group of

students in the west.

-

The Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai, the society for the

preservation of Japanese art swords in Tokyo, headed by Mr. Hosokawa and Dr.

Homma. They issue certificates in several grades from Tokubetsu Kicho (white

paper), Marutoku (green paper), to higher grade certificates, which are

issued only after a board of experts has passed on objects submitted for

their consideration.

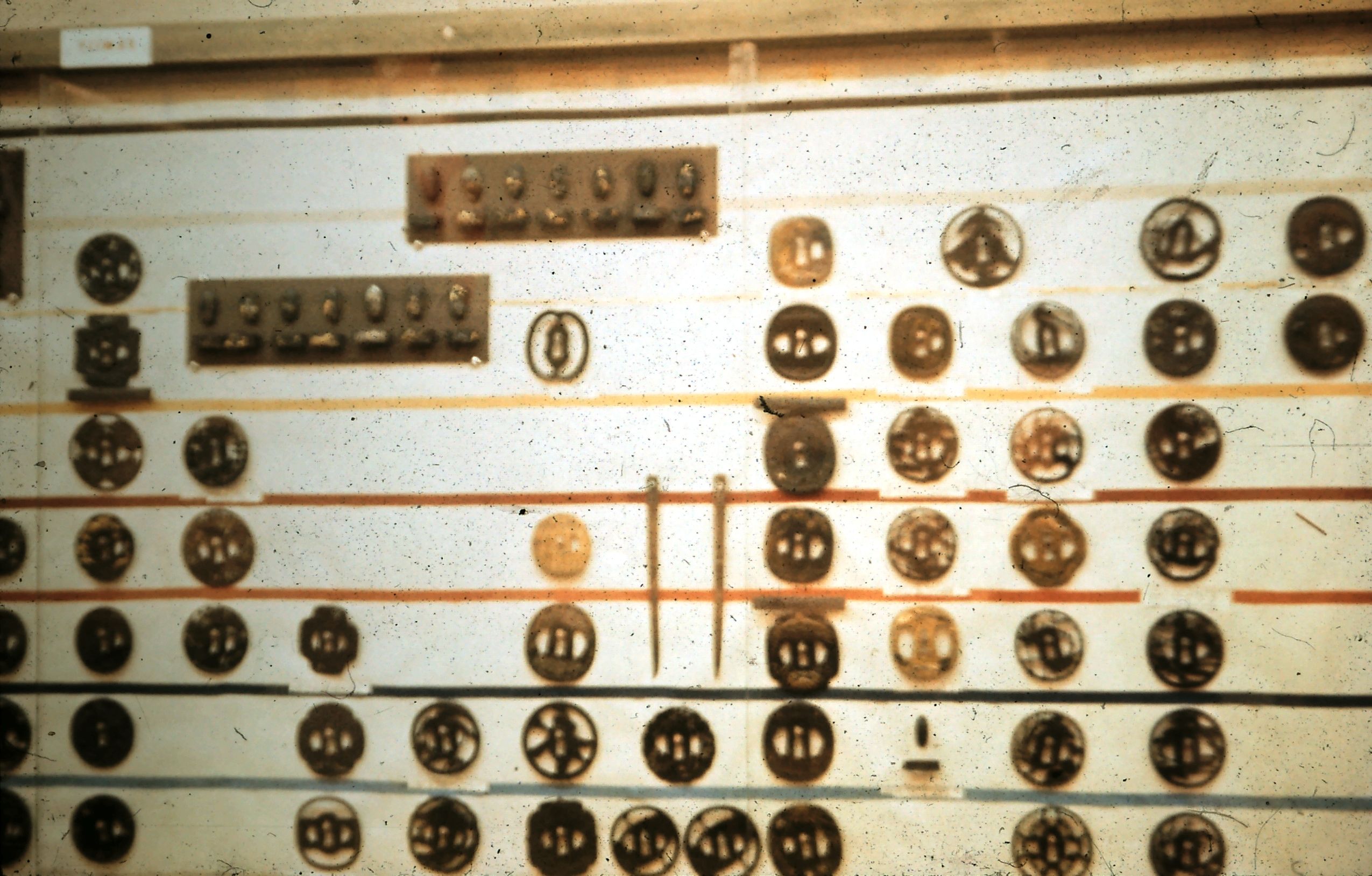

Robert E. Haynes

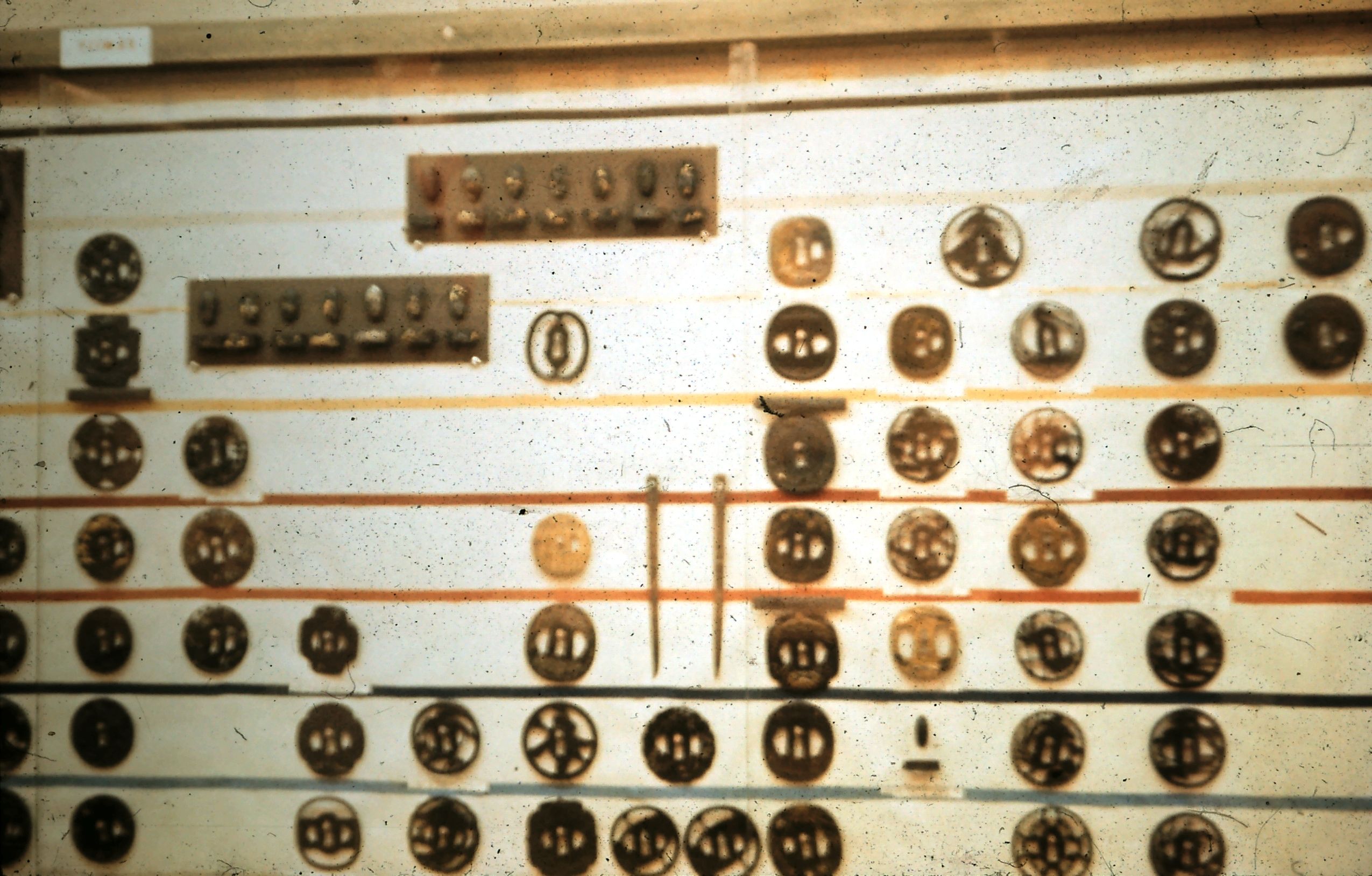

Tsuba on display at the exhibit.

Return to the Table of Contents

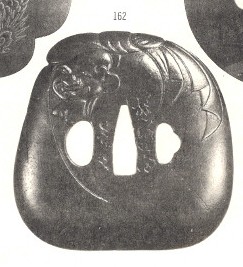

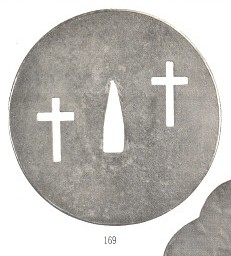

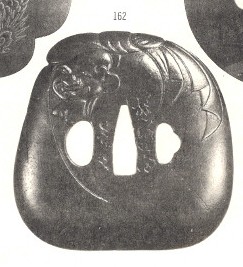

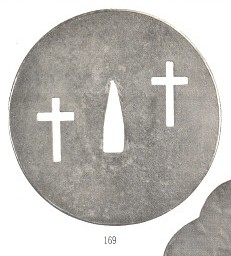

The earliest extant tsuba were made prior to the eighth

century. They are the HOJU type, either iron plate, rarely decorated with

silver inlay, or copper plate, usually covered with sheet gold. The iron

plate example (described as number 5 in the sword section) is typical of the

later style of Hoju tsuba.

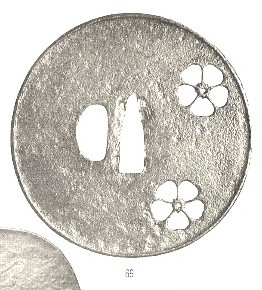

Examples of tsuba made in the Nara period (710-793) are

almost nonexistent outside of Japan. A few examples of tsuba of the Heian

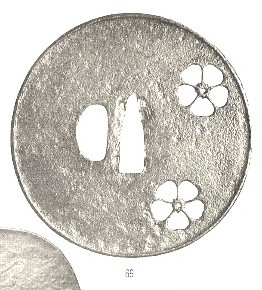

period (794-1185) are to be found in the West, such as number 65 (not

illustrated).

A copy of the leather plate style of tsuba (Nerikawa tsuba) is displayed and shows what the original type of this tsuba made in

the Heian period resembled. The rim cover of gilt copper and the black

lacquer surface are typical of the old leather fighting tsuba. Another

leather tsuba, probably of the Kamakura period (1186-1333) has a center core

of iron and a raised lacquer decoration on the surface. This is a very rare

example.

-

(Not illustrated) A typical fighting tsuba of iron

plate made in the late Kamakura period (circa 1300) illustrates this

rare type. The raised design (a wide relief line) was at one time

covered with sheet gold; only vestigial specks remain. The two side

perforations (hitsuana) were added at a later date. the reverse side is

flat and without decoration. This is a very rare example of the Kamakura

katchushi tsuba. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo.

Illustrated in the Tsuba Geijutsu Ko (1960), top of page 7. Thickness at

center, 3.25 mm; at edge, 3 mm.

|

|

5 Not illustrated.

65

Not illustrated.

66

Not illustrated. |

Return to the Table of Contents

Swordsmith tsuba made prior to 1450 are exceedingly rare.

The few examples extant are treasured by shrines and private collectors in

Japan. From 1450 forward, examples are more numerous, but do not become

common until the nineteenth century. At that time many of the famous Shinto

and Shin-Shinto swordsmiths turned their hand to the making of tsuba in the

popular style of the day or in the Nobuiye revival style.

-

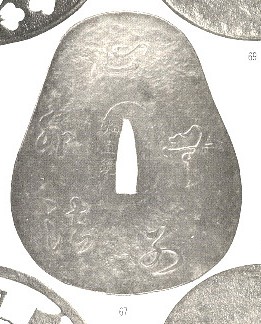

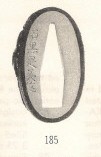

Signed Hata Naoaki, worked about 1860. Student of

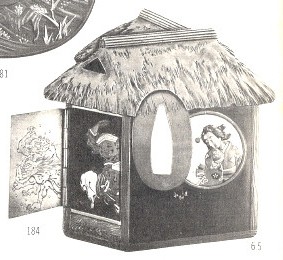

Shoji Naokatsu I. the shape of this tsuba represents the Daruma.

Thickness 4.5 mm.

|

|

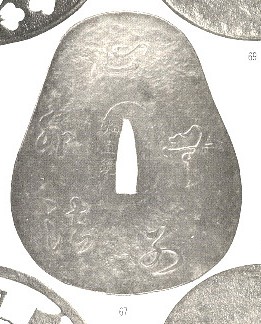

67

|

Return to the Table of Contents

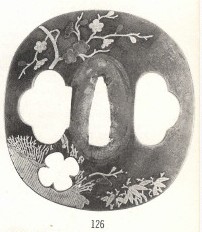

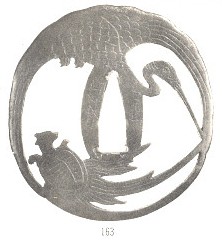

Large tsuba of thin plate with simple perforations are

commonly called armorsmith tsuba, though there is no proof that the were

actually made by the ancient armorers. It is more likely that they are the

work of the earliest professional tsuba makers, though their individual

identity is unknown. Examples date from about 1350 to 1900.

-

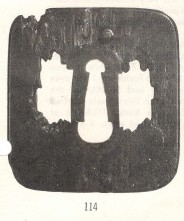

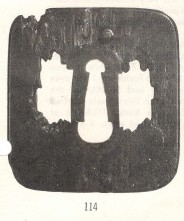

Unsigned. Rare example of the early Muromachi (1425)

style of armorsmith tsuba. The shape of the hitsu-ana has been changed

at a later date. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness

at center 2.75 mm, thickness at edge 6 mm.

-

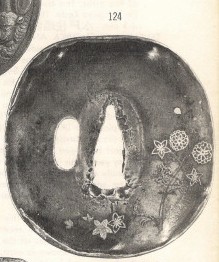

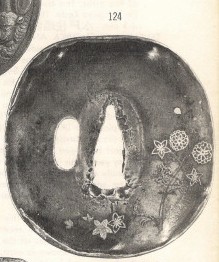

Unsigned. Typical example of middle Muromachi (1450)

armorsmith tsuba. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness

at center, 2.5 mm; at edge, 3.75 mm.

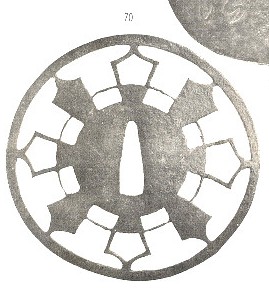

-

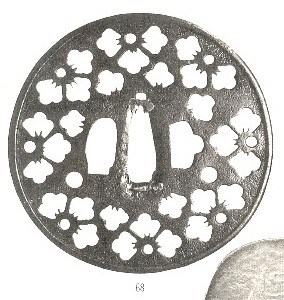

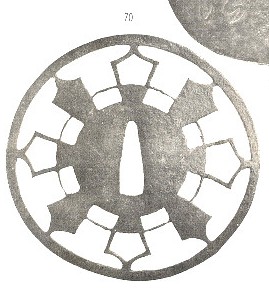

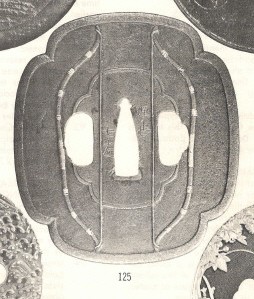

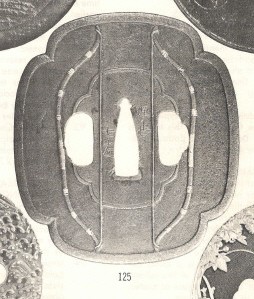

Unsigned. Rare design of middle Muromachi tachi

armorsmith tsuba. Thickness at center, 2.25 mm; at edge, 3.25 mm.

|

|

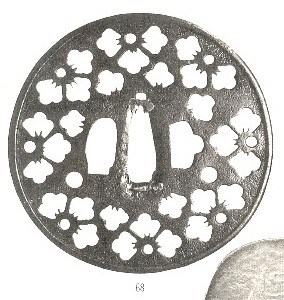

68

69

70

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The genealogy of this family is recorded, though it is

thought to be in error since it is now known that there were several

generations who used the same name, such as Iyesada and Iyetada.

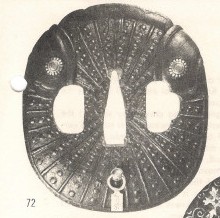

-

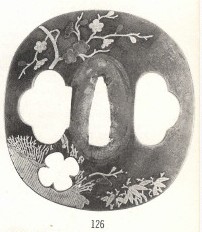

Unsigned. A typical early example of the work of this

school. Thickness at center, 2.75 mm; at edge, 4.5 mm.

-

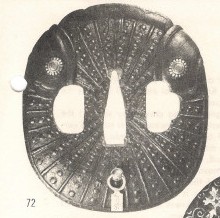

Signed Odawara (no) ju Saotome Iyesada. This tsuba is

considered to be a masterpiece of the Saotome school. It was made about

1625. A gold tag affixed to the ring on the back of the helmet has the

name Fujiwara Morifusa inscribed. This is probably the name of the

owner. Thickness at center, 2.5 mm; at edge, 3 mm.

|

|

71

72

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The artists of this school were students, or followers,

of the Saotome masters. The majority of their work is of common quality;

though in rare cases they created a few noble pieces. Signed work, such as

Yamashiro (no) ju Tempo, Sanada, or Sanoda Tempo, is slightly better than

the average example. This school worked during the Edo period (1600-1850).

|

|

No illustrations.

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The name for this style of tsuba is said to be derived

from a type of lacquer decorated with a similar style of carving, known as

Kamakura-Bori lacquer. There is a theory that a few examples of the tsuba of

this style may actually date from the Yoshino period (circa 1350), though

there is no proof of this at this time. This style of tsuba went out of

fashion in the early seventeenth century. There are no signed examples.

|

|

No illustrations.

|

Return to the Table of Contents

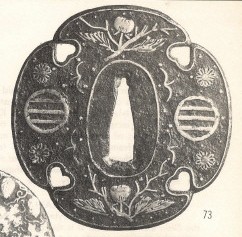

The name for this school style is taken from the Onin era

(1467-68). It is thought that this style of tsuba was made at least fifty

years prior to this date and for a hundred years after. A few examples were

made during the Edo period. Individual artists are unknown and there are no

signed examples.

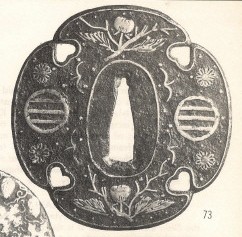

-

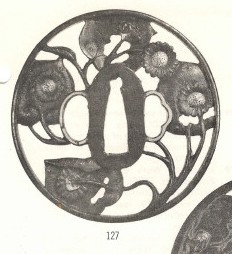

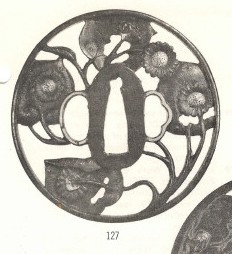

Unsigned. Classic style of brass inlay Onin tsuba,

intended for mounting on a tachi, but later used on a katana. Thickness

3.5 mm.

|

|

73

|

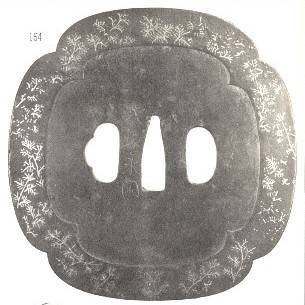

Return to the Table of Contents

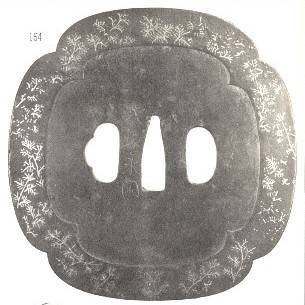

The name for this school is derived from the area of

which Kyoto is the center. The individual artists signed their work in rare

cases, but no family or school seems apparent. The school style is

characterized by the decorative inlay of brass, either flush to the plate

surface, or slightly raised above it, or a combination of the two. Ninety

percent of all brass inlay tsuba are the work of this school which was

active from about 1450 to 1850.

-

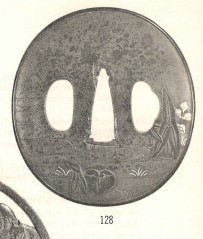

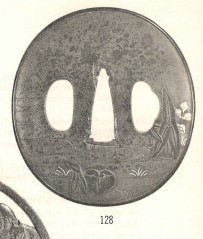

Unsigned. Classic style of brass inlay Heianjo tsuba.

Circa 1580. Thickness at center 5 mm.

-

Unsigned. Later work of this school, circa 1700.

Flush inlay of brass, copper, and silver. A masterpiece of this type.

Illustrated in the de Haviland collection catalogue, page 53, number 29. Thickness

at center, 4 mm; at edge, 3 mm.

-

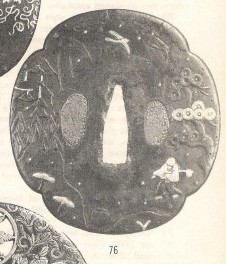

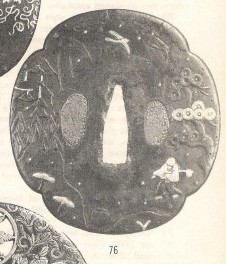

Unsigned. Brass inlay style of about 1600. Good

example of pictorial style. Thickness at center, 3.5 mm; at edge, 4.75

mm.

|

|

74

75Not illustrated.

76

|

Return to the Table of Contents

In addition to the above two schools there were the Kaga

and Koike Yoshiro schools of brass inlay style. A few members of the Koike

school moved to Okayama in Bizen. They worked there for a few generations

during the Edo period. The Kaga school extended through the entire Edo

period.

-

Unsigned. Kaga crest inlay style of the earliest

type, very rare. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness

3.25 mm.

-

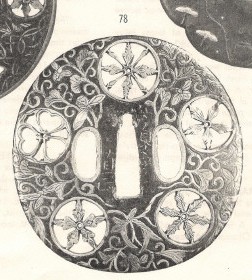

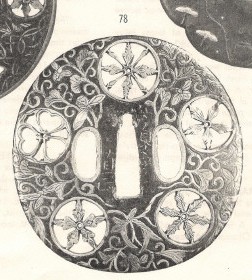

Signed, Izumi (no) Kami Yoshiro Koike Naomasa. One of

the masterpieces by this artist. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye

Kodo. Thickness at center, 4 mm; at edge, 3.5 mm.

-

Signed, Yoshiro saku. A typical example of the Bizen

Yoshiro school. Illustrated in the Mosle collection catalogue, number

470. Thickness at center 4.25 mm.

|

|

77

78

79Not illustrated. |

Return to the Table of Contents

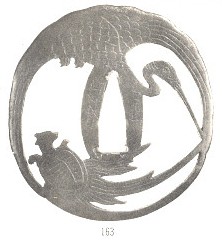

This school had a parallel development to the Heianjo

brass inlay school. By the seventeenth century, the two schools were

completely integrated. The early style of this school is characterized by

designs in bold positive openwork with occasional sparse brass inlay. A few

signatured examples exist but they seem to be independent artists.

-

Unsigned. Earliest style of this school. There are

three brass dots of inlay on the face and two on the reverse side. Thickness

3.5 mm.

|

|

80

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The development and growth of the Kyoto openwork school

was parallel to, but slightly later than, the Heianjo openwork school. Its

beginning was about 1550 and it reached its peak by 1580. The style was made

until late in the Edo period; but the quality was in continuous decline

during this time. The Daigoro school was a branch development of the Kyoto

openwork school shortly after 1700. Their style gave new impetus to the then

stagnant designs of the parent school.

|

|

No illustrations.

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Kaneiye tsuba may be divided into many classes. First are

the few extant examples by the first master, who signed Joshu Fushimi (no)

ju Kaneiye. Then there are the examples by the first artist, who signed

Yamashiro Kuni Fushimi (no) ju Kaneiye. In addition there are a few signed

and unsigned examples made by students and followers of the second artist.

Next there is the Saga Kaneiye school work. These are the work of the later

followers after the school had moved to Saga in Hizen. They were made from

1600 to about 1850. In addition to the Saga style, there are numerous

examples made at Aizu or on the docks at Yokohama as imitations for sale in

Tokyo or to the foreigners. These imitations of the Saga style comprise more

than eighty percent of the existing signed or unsigned Kaneiye tsuba.

-

Signed Yamashiro Kuni Fushimi (no) ju Kaneiye. A fine

example of the earliest student work, about 1625. The quality of the

inlaid gold and the iron plate are both excellent. This tsuba is

illustrated in the G. H. Naunton Collection catalogue (1912), plate XI

number 21. Thickness at center, 3.75 mm; at edge, 4.25 mm.

-

Unsigned. Early example in Saga style employing a

design found on the work of the first and second Kaneiye. Thickness at

center 4.25 mm.

|

|

81 Not illustrated.

82

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Tsuba signed with the name Nobuiye are rather common.

They may be divided into the following types: the first and second Nobuiye

who lived during Momoyama to early Edo period (1550-1625); the dozen or so

artists who used this name from 1625 to 1850 and worked in various

provinces, such as Kaga, Kozuke, and Akasaka; the many forgeries in the

style of the first Nobuiye made by Iwata Norisuke (first and second) and

lesser imitators, who cashed in on the revival of the Nobuiye style about

1850. These forgeries account for the majority of the Nobuiye tsuba that are

seen today.

-

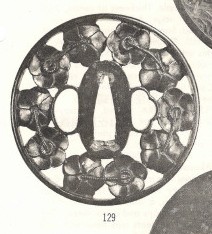

Signed Nobuiye. A typical example of the work of the

first master, about 1575. The carving of the design is very delicate and

the edge and feeling of the plate surface show the taste of this period.

Illustrated in the Tsuba Geijutsu Ko, top of page 35. This tsuba is

certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness at center, 2.5 mm; at edge,

4.5 mm.

-

Signed Nobuiye. A Typical example of the work of the

second master, about 1600. Shows the power and strength usually to be

found in the work of this artist. This tsuba is certified by Dr.

Torigoye Kodo. Thickness at center, 4 mm; at edge, 5.5 mm.

|

|

83 Not illustrated.

84

|

Return to the Table of Contents

There are no known examples of tsuba by Myochin masters

signed with the family name that were made before the early Edo period.

After 1700, tsuba by this school were made in great quantities and followed

the style of various prevailing schools of the later Edo period. One cannot

say there is a typical Myochin style. The quality of the later work of this

school is rather common.

-

Signed Myochin Ozumi (no) Kami Ki Muneto. This is the

second generation of this name, worked about 1750. In the family

genealogy he is listed as the twenty-sixth master. This is a fine

example of later Myochin work and shows this school at its best during

the later Edo period. Thickness at center, 5.25 mm; at edge, 7 mm.

|

|

85

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Authentic examples by the first two masters of this

school are very rare, though forgeries of their work may be found by the

dozens, most of which were made by the first and second Iwata Norisuke, (at

least the better ones were). This school of Owari province particularly

appealed to the samurai class. Tsuba of this school are usually signed.

-

Signed Yamakichibei. An excellent example dating

about 1600. The shakudo inlay and rim were added at a later date. Thickness

at center 3 mm.

|

|

86 Not illustrated.

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The first examples of this style of tsuba were made

during the period from 1450 to 1550. The second period of production is from

1550 to about 1625. The third period, consisting mainly of imitations of the

first periods, extends from 1625 to about 1800, then the style disappeared.

The majority of the extant examples are from the third period.

-

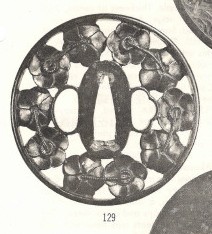

Unsigned. Rare example of the early work of the

second period, dating about 1550. This tsuba is certified by Dr.

Torigoye Kodo. Thickness at center, 4.5 mm; at edge, 6 mm.

|

|

87

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The style of this school is very difficult to define. The

early work resembles that of the Yamakichibei school; but after the third

generation the style became mixed with that of other schools. The only

characteristics of the school are thick plate and many examples with acid

etched designs. The Hoan divided into several groups and at least two of

these moved from Owari province to start new branch schools.

|

|

No illustrations.

|

Return to the Table of Contents

There were several independent small groups who worked in

the Owari area in addition to the three schools mentioned above. The first

and second Sadahiro were independent artists whose work is almost invariably

of good quality and shows fine treatment of the iron plate, with strong

decoration, and small amounts of inlay.

-

Signed Sadahiro. A typical example of the first

master. This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness at

center 4 mm.

|

|

88

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Little is known of the artists who signed Nara Kaji,

except their names, and the approximate period in which they worked. The

best examples show a strong resemblance to good Owari style work, rather

than Nara style. Examples of this school are exceedingly rare.

-

Signed Nara Kaji Iyekuni. This is a good example by

the best artist of this school. Date about 1600. Thickness at center, 4.75 mm;

at edge, 5.5 mm.

|

|

89

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The style of tsuba made by this Owari school was very

popular with the samurai as early as the middle of the Muromachi period

(1450). This popularity continued until late in the Edo age. First period

examples date from 1450-1550. Second period examples date from 1550-1650.

Third period examples, after 1650, are imitations of the first two periods.

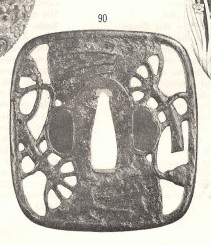

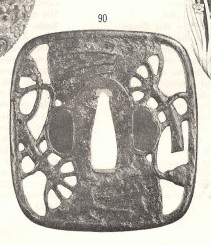

-

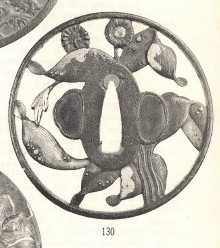

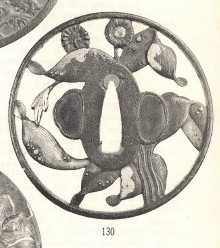

Unsigned. Good example of the late second period

style, about 1600. Thickness at center 6 mm.

|

|

90

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The Yagyu style did not appear until the middle of the

Edo period (1750). It was very popular for about one hundred years.

Originally the designs used for these tsuba were thirty six in number

(san-ju-roku kasen); later this number was expanded to more than a hundred

and fifty designs. There were also imitations made by other schools in the

Owari area.

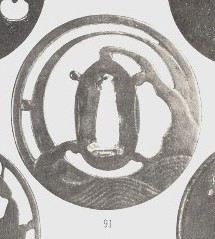

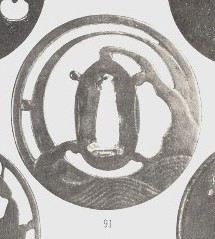

-

Unsigned. Typical example of classic style of this

school. Thickness at center 6.25 mm.

|

|

91

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The date of origin of the first mirror maker tsuba, of

cast bronze, is not known. At this time the date is fixed as about 1400 or

slightly earlier. Examples of Yamagane plate were made until the early Edo

age. Examples in brass were made from 1600 to about 1750.

-

Unsigned. Cast bronze with center pattern resembling

those used on very early bronze mirrors, dating about 1400. This tsuba

is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Illustrated in the Tsuba Geijutsu Ko

bottom of page 17. Thickness at center, 2 mm; at edge, 3 mm.

-

Unsigned. Cast bronze with pictorial style of design.

Excellent example of this type. Date about 1450. Thickness at center, 2.75 mm;

at edge, 4.75 mm.

|

|

92 Not illustrated.

93

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Tsuba and other mountings made by these artists date for

the most part from the middle of the Muromachi period (1450). They were

continuously made for the next three hundred years; but the quality steadily

declined.

-

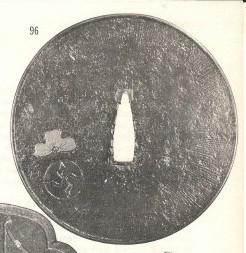

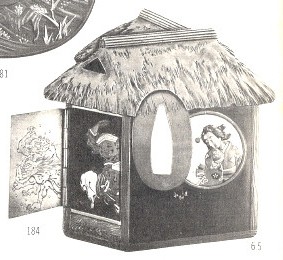

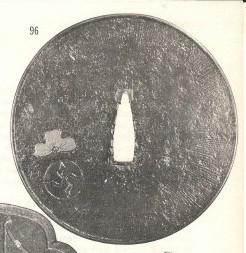

Unsigned. Shakudo plate with sheet gold inlay on

flower pattern. The style resembles the iron plate tsuba of about 1450,

when this tsuba was made. The tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness

at center, 3 mm; at edge, 7.5 mm.

-

Unsigned. Solid silver plate with stamped raised dot

surface (nanako) deeply carved flower design. The edge covered with

scroll work in line carving. The hitsu-ana are typical of this style and

the period (about 1450). This tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness

at center, 4 mm; at edge, 4.5 mm.

-

Unsigned fuchi-kashira. Tachikanagu-shi style of

1450. Yamagane plate with inlay of copper and silver.

-

Unsigned menuki. Yamagane plate, no inlay.

Tachikanagu-shi style, about 1400.

|

|

94

95

96

97

|

Return to the Table of Contents

Tsuba of this type were made by unrecorded artists who

worked in the period from 1400 to 1600. Some were students of the Goto

school and there is an uncertain relationship to the later Kinko schools

which developed from these earlier styles.

-

Unsigned. Shakudo plate with carved wave design. The

rim is brass and the only one of its kind known; date about 1400. This

tsuba is certified by Dr. Torigoye Kodo. Thickness at center, 2 mm; at

edge, 5mm.

-

Unsigned. Shakudo plate with raised dot surface (nanako);

made about 1450. Typical example of Ko-Kinko work of Goto derivation. Thickness

at center, 4.5 mm; at edge, 5 mm.

-

Unsigned fuchi-kashira. Ko-Kinko style of 1450.

Shakudo nanako plate with gold inlay.

|

|

98

99

100

|

Return to the Table of Contents

The Goto developed in Mino province during the Muromachi

period (ca. 1400). Goto Yujo (1440-1512) and his followers were the main

line of this school after moving from Mino to Kyoto about 1460. The Kyoto

school became the dominant group and gave birth to the many branch schools

of the Edo period. The Kaga school was independent of the Kyoto school

during the Edo period.

-

Unsigned. Shakudo plate with gold decoration dating

about 1650. A typical example of the Mino Goto school. Thickness at

center 3.25 mm.

-

Unsigned fuchi-kashira. Mino Goto style, about 1675.

Shakudo plate with gold surface over deep carving.

-

Signed Teitogu (resident of the capital) Masaoki

(Goto Seijo III), with gold seal: Homeido. Shakudo plate with surface

decoration in imitation of Portuguese stamped leather. The third Seijo

lived from 1747 to 1814. Illustrated in the Mosle Collection catalogue

number 382. Thickness at center 4.75 mm.

-

Unsigned kogai. Attributed to Goto Kojo (1529-1620),

fourth master of main line, first son of third master, Joshin. In this

example, Kojo was imitating the style of the first Goto master, his

great-grandfather Yujo (1440-1512). This kogai is certified by Dr.