|

|

by Dean Hartley in collaboration with Thomas B. Buttweiler

Contained as a chapter in the Northern California Japanese Sword Club Token Taikai '76 Lectures

|

|

Most of our modern collectors of Japanese arms and armor have a tendency to think that we have only just now invented the collecting of these magnificent and beautifully artistic articles of war. That is perhaps a natural feeling for anyone with a newly discovered enthusiasm; but the facts are that Japanese arms and their accoutrements have been wandering about the world since around 1007-1072 (in the Chinese Sung Dynasty). This period coincides with the Japanese Heian period (794-1191) and is the period during which the Nippon-To achieved the shape and qualities which have persisted through the ages.

It is, in fact, from this period that the term "Nippon-To" was applied to the Japanese sword, resulting from the earliest written reference to an interest in Japanese swords by people outside of Japan. In this period, Ou Yang Hsiu wrote of the "Nippon-To" which were so eagerly sought by the Chinese, "Treasure swords are obtained from the east [Japan] by merchants of Etsu. Their scabbards are of fragrant wood [probably impregnated with the oil of cloves used in preserving the swords from rust] covered with shark-skin. Gold, silver, copper, and metals adorn them. Hundreds of gold pieces is their cost. When wearing such a sword, one can slay the barbarians."

Obviously a reputation for quality had already been established - a reputation which remained virtually intact through the centuries. Joao Rodriguez, a Jesuit priest who came to Japan in 1585 and stayed for about 40 years as a priest and confidant of Tokugawa Iyeyasu, during which he learned to speak, read, and write Japanese fluently, has written, "Some Lords may ask other nobles for some men who have been condemned to death in order to see whether their sword cuts well, whether they can trust it in emergencies. They often sew up bodies which have been cut by swords and put together the severed parts so that they may once more cut and see if the sword passes through the body with one blow. They indulge this and other types of slaughter and leave the bodies in pieces in the fields for the dogs and birds; and do not bury them. The delight and pleasure which they feel in cutting up human bodies is astonishing, as it is also the way young boys sometimes indulge in this." John Saris, an English salesman, came to Hirado in 1613 and, as a result of his experiences and observations, wrote, "Every man that listed came by to try the sharpness of their katana upon the corpses so that before they left off they had hewn them all three into pieces as small as a man's hand."

Rodriguez further comments on the swords after this and he is referring first to carpentry in comparison. "After this comes the working iron, principally for the offensive weapons which the Japanese prize so highly. This art competes with the previous one as regards nobility and esteem, and there arises great disputes among them whether this art for architecture in wood occupies the first place of all the mechanical arts [or whether the art for metal work does]. In olden days, there used to be fine armorers who were very famous in this art because their weapons are now of great value for their perfection in cutting and everything else. Scimitars, daggers, blades of lances of war size [here he is referring to naginata or nagamaki], arrow heads and others which are valued. Swords and daggers, as we have noted, are worth many thousands of quesados and even nowadays through the whole kingdom there are craftsmen who are very skillful with these weapons. Experience shown that Japanese weapons are in general the best and cut better than any others. One of their ordinary swords can cut a man through the middle into two parts with the greatest of ease, while a dagger or sword of one and one-half of at most two spans in length will part a man's head from his neck and a lance will do the same, for their blades are such that they not only wound with a thrust but also cut like swords. an arrow with a special head which is a wide moon shaped blade made for the purpose will cut a man's throat. When it is the product of a distinguished craftsman who is esteemed for this, this is a Kabura-Ya."

Rodriguez discusses Kantei, "There are certain experts whose office is to recognize by their style and marks the swords, daggers, and other iron weapons made by ancient and famous craftsmen. Such weapons command a high price and esteem among the Japanese; not only on account of their age and the smith who made them, but also much more because they are excellent weapons which will cut anything without notching or blunting the cutting edge. Nor do they rust like modern weapons because they are made of extremely pure iron and steel. Some of these blades cost 2-3-4-5 thousand quesados and the very best even ten thousand. We saw one like this in the hand of Taiko, who bought it from the Yakato of Bungo for 10 thousand quesados. It was called "Hone-Bane," that is the devourer of bones. For even when it touched them lightly, it cut them like lopped turnips. This is highly esteemed and important art among the Japanese and even the noble lords devote themselves to it so that they may not be deceived when they deal for such valuable things. Some of these blades bear the marks of the craftsman who made them. There are many, many false and counterfeit ones. Others do not bear any marks but there are infallible rules which make it possible to distinguish the genuine blades from the false ones, the old from the new, and those people who are skilled in this matter are so expert that they never make a mistake. In the time of the present Shogun, the son of Daifu, there lived in Miyaka a Christian whose family name was Takira and his forefathers were skilled in this art. The Shogun summoned him and laid before him one hundred different swords for him to identify. He drew them out one by one from their scabbards and, without looking at any marks on the blade, he identified each without a single mistake. The Shogun was full of astonishment at such a rare feat and wanted to present him immediately with a royal patent, as is the custom, and raise him to the supreme rank of Ten-Ka-Ichi ["First under heaven"] of his art in Japan and this carries with it many advantages and much honor. This happened during the present persecution against the Christians and the Shogun was not aware that he was a Christian. This good man told the Shogun that he was a Christian and he was informing him of this in case it was an impediment against his receiving the rank which the Shogun wished to bestow upon him. The Shogun pondered for a little while and replied that it did not matter - that he should go ahead and accept the rank. He seemed to have answered thus because he did not wish to lose a man so outstanding in this art."

Rodriguez continues, discussing sword fittings. "Nor are the mean whom we would call goldsmiths less superior in the art of working gold, silver, and copper and they are superior to the Chinese and any other nation in the orient with regard to their excellence, the type of work, and the mixture of copper with silver and gold with which they make a third metal which they call black copper [this is obviously shakudo]. This is highly esteemed among the Japanese and they use it to make certain instruments which they insert in sword scabbards and which is decorated with a flower or an animal carved by very skilled craftsmen [this would be kozuka and kogai]. These men are highly regarded by them and enjoy high esteem in the art of working gold and silver. This sort of engraving of trees, plants, birds, water and land animals, and ancient legends on copper is extremely fine and life-like in every detail. They greatly esteem such engraving done by hand; but this is not so with the work that has been cast, however good it may be. They are incomparable in embellishing and engraving with gold and silver or inlaying gold with silver and silver and black copper with gold and all of it engraved. This is something very excellent and attractive and work of this kind is found only among the Japanese. A genuine good and choice item made by craftsmen outstanding in this art and esteemed by the Japanese has yet to find its way to Europe. But some crosses of black copper and silver inlaid with gold have gone over. But these were made by some of the many ordinary craftsmen throughout the kingdom. In Miyako there is a certain family which is the head of this art. They make things of the king, the Kubo, and Lord of Tenka and other Lords. However small their work may be, it is highly prized and valued both for the skill and excellence of craftsmanship and also for the perfection and combination of materials. This family is called Goto and we saw some of their work which was indescribable perfection and skill. Even if such a small and minute thing were cast, it would not seem possible to produce so delicate a piece of work, all apart from the outstanding perfection of the parts. This is not exaggerated or excessive and indeed it falls short of what could be said in all truth about the matter." This would indicate that by 1600, fine sword ornaments had not reached Europe; but that some ordinary export crosses had indeed been manufactured for sale or gifts in Europe and the Goto material still remained in Japan.

In the late 19th century, for example, Professor Basil H. Chamberlain wrote in his Things Japanese, "Japanese swords excel even the vaunted products of Damascus and Toledo. To cut through a pile of copper coins [or a body or two] without nicking the blade is, or was, a common feat. History, tradition, and romance alike re-echo with the exploits of this wonderful weapon." Of course we today continue to uphold this superiority and have the multiple-body tameshigiri to sustain our beliefs.

It would probably be appropriate to divide the chronological periods of "foreign" interest in Japanese arms into five basic segments. These would begin with "early history" - say 800 A.D. to the advent of Europeans into Japan around the middle of the 16th century, a "short-middle" period covering the peak of European influence in Japan in the 16th and 17th centuries (followed by some 250 years of seclusion), a "middle" period from the opening of Japan by Commodore Perry in 1853 to the Haitorei Edict in 1876, at which time the wearing of swords as every-day wear was prohibited, a "late" period from the Haitorei Edict to World War II, and a final period from World War II to the present.

In considering these five periods, certain interesting differences occur. For example, as mentioned earlier, even in the Sung period, the reputation of the Japanese sword had been solidified and we have Ou Yang Hsiu's comments. Not too long afterward, during the period of Juan, or Mongols (Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan), one Marco Polo was in the Chinese court and in his writings refers to "... the weapons of Cipengu [Japan]." This was in the period around 1280-1300. There was also instituted around 1032 - and lasting to 1547 - a series of eleven Kon-Go trade missions between Japan and China. It is estimated that between 100-300 thousand swords were exported to China in this period. It must be assumed, since Marco Polo had established trade relations between Europe and China - relations which were to continue and grow from that time on - that some of these swords, and the unique style of Japanese armor, must have found their way to Europe. As an indication of this, at the battle of Omdurman in 1898, Sir Winston Churchill reported that one of the dervishes slain by Lord Kitchener's troops was wearing a partial suit of Japanese armor. One may wonder at the slow progress of this armor westwards, to end up in near modern times in Africa. With regard to this period, Captain Frank Brinkley notes that, around 1420, a brisk trade was carried on between Japan and China, where "... a sword costing one kwan-mon in Japan fetched five kwan-mon in China." Already the pattern has been set.

With the landing of the Portuguese ship on the island of Tanegashima, off the southern coast of Japan, in 1542, we enter the second or "short-middle" phase. As was inevitable during that period, the priests were hot on the heels of the explorers and the traders immediately behind them - and all protected and reinforced by the fleets and soldiers. These "visitors" were at first welcomed by the Japanese and were given the highest recognition and finest gifts the Japanese had to offer - specifically, swords. Joao Rodriguez reports that blades by Kunifusa, Mitsutada, Sadamori, and Akihiro - in addition to two suits of armor - were given to Viceroy Mathias De Albuquerque by Hideyoshi, over the objections of his retainers, who maintained the Viceroy could not possibly appreciate the extent of the honor represented by these blades. During this period, it was customary to honor foreigners and their sovereigns with gifts of swords. For example, there is now a group of swords in the Etnografic Department of the National Museum in Kopenhagen, Denmark, which belonged to King Frederick III - and so cannot date after 1670. At the same period in Denmark, artist Karl Van Manders possessions at his death included "two Japanese daggers."

It is doubtful if there was any further significant export of swords, especially to Europeans or Americans, after Japan was "closed" in the mid-1600s until Commodore Perry's "re-opening" with his landing on 8 July, 1853. Perry's journals refer to a number of swords that were presented to the President at that time. In addition, a fine sword was presented to Perry himself (now in the Smithsonian Institution) and others to members of his crew and staff. One of these, a blade signed Hizen no Kuni Kawachi no Kami Fujiwara Masahiro, in tachi mounts, was presented to Major Jacob Zeilen and is now on display in the Marine Corps Museum in Quantico, Virginia. Others were given to other individuals. Similarly, blades of quality were presented to other heads of state, as for example, a tachi by Magoroku Kanemoto, which was presented to Queen Victoria by Shogun Iyemochi in 1860, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. During this middle period, many rather fine blades were presented to various dignitaries and governmental representatives, the "face" or prestige of the Japanese being at stake, as Hideyoshi had pointed out in the 16th century.

However, with the accession of Mutsuhito - that is, Emperor Meiji - to the throne in 1867 and the return of power from the Shogun to the Emperor, Japan entered the modern world. Emperor Meiji acted to break up the feudal system under which Japan had operated - and remained stagnant - for so many centuries and to re-direct the energies and imagination of his people toward joining the rest of the world. He issued in 1876 the Haitorei Edict, which in effect deprived the daimyo of their great powers, abolished the samurai class as such - and, in so doing, made the Nippon-To, that symbol of the rights, prestige, and power of a select group, nothing more than a cutting weapon. From that time until just before World War II, the sword had in general little meaning. They were tied in bundles and sent to Europe for sale as souvenirs. Some non-Japanese, however, recognized the inherent artistic qualities of the swords and their fittings. Tourists swarmed over the land, picking up mementos, with individuals of each nationality revealing some of their national traits in the way they collected.

The British did then - and still do to a certain degree - concentrate on the ornate and unusual. There are - or have been - quite a few very fine collections such as the Gilbertson (now dispersed), the David Craig (status unknown), and that of Sir Francis Festing (still intact). The Victoria and Albert Museum has maintained one of the few properly organized and catalogued collections, under the able oversight of Basil W. Robinson, Deputy Keeper of the Department of Metalworks (now retired). There were many genuine students in England and much of the available information available in English came from publications of their studies in the Transactions and Proceedings of the Japan Society, London.

The French tended to specialize in archaic items and some of the best of the very fine, very old collections of tsuba, kodigu, etc., are found in French collections. The Germans, in their normal organized, systematic manner, collected representative examples of each known school. Their collections probably constitute the best reference and study groups outside of Japan. There are also large - and primarily colorful or gaudy collections in Czechoslovakia and Italy (Museo Orientale in Venice), as well as other countries.

The Americans, as fits their polyglot origins, made polyglot collections.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts has about 575 blades, only recently thoroughly studied and catalogued - but not yet published by Ogawa Morihiro. The Boston Museum seems to have had a special team wandering the countryside of Japan, picking up everything from junk to (literally) National Treasures. Edward S. Morse specialized in Japanese ceramics. Fenellosa collected paintings, scrolls, and Koku-ho quality Heian makimono. The Bigelow collection (presented by the son of the Dr. Bigelow who taught Walter Compton at Harvard) constitutes the core of the Boston Museum's sword collection, with significant additions of the Weld Collection and from Major H. L. Higginson.

Frank Lloyd Wright, a great admirer of Japan, had a fine collection, now broken up, with about half in the collection of Graham McQuire (near Minneapolis) and the remainder dispersed.

The collection of T. B. Walker, a Minneapolis lumber baron, was put together in the 1880s and was installed in the Walker Art Institute, which was built for this purpose. The many hundreds of tsuba, hundreds of swords, and many suits of armor were disposed of in 1948 for the grand total of $550.00.

The Avery Brundage collection, which I had the good fortune to see in part, was largely destroyed by fire in his Santa Barbara home around 1965, although some of the iron tsuba were refinished by Tom Buttweiler and disposed of in Japan.

There is a fine collection in the Walters Museum in Baltimore - practically inaccessible.

The Gunsaulus fittings collection in the Field Museum in Chicago has been, I am informed, "cleaned up," and is not available (translate - "the rust has been cleaned off of the iron tsuba and the 'corrosion' polished off the soft metal ones.") I have not seen this collection and I hope this report is false. If it is true, it is not an unusual example of what happens to collections of Japanese blades and fittings in the hands of uninformed museum curators. I insert a plea here - if you don't know what you are doing in "restoring" any of these items, DON'T!!!

The Metropolitan Museum collections, mostly from the Stone collection, has fine armor; but the blades are open to question.

In addition, blades in bundles were sold in Louisiana, fitted to machete handles, and used for cutting sugar cane.

Further, in Francis Bannerman's catalogue for 1911, Samurai swords were offered at $3.00 each for insertion into regulation Army mounts for fighting in the Philippines.

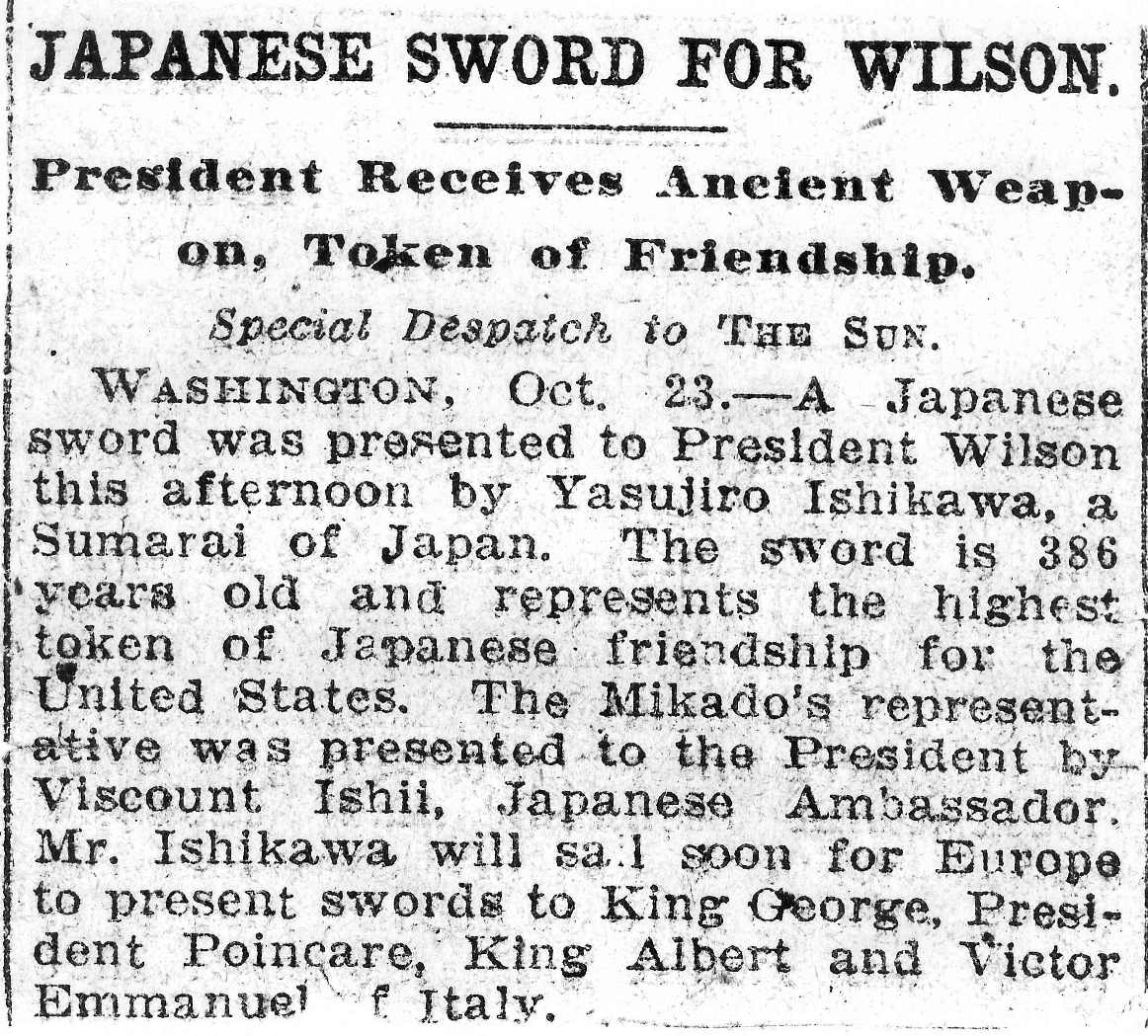

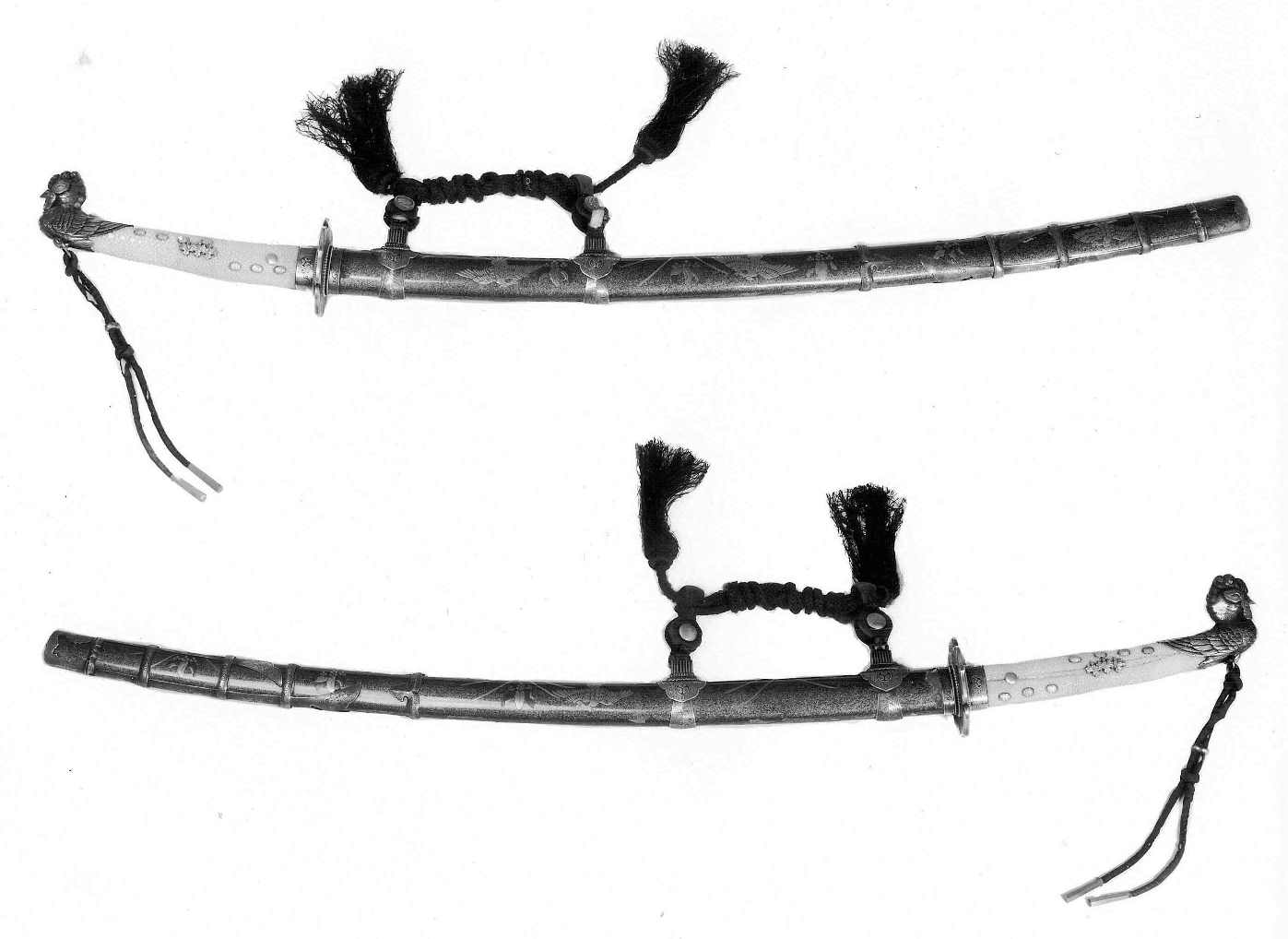

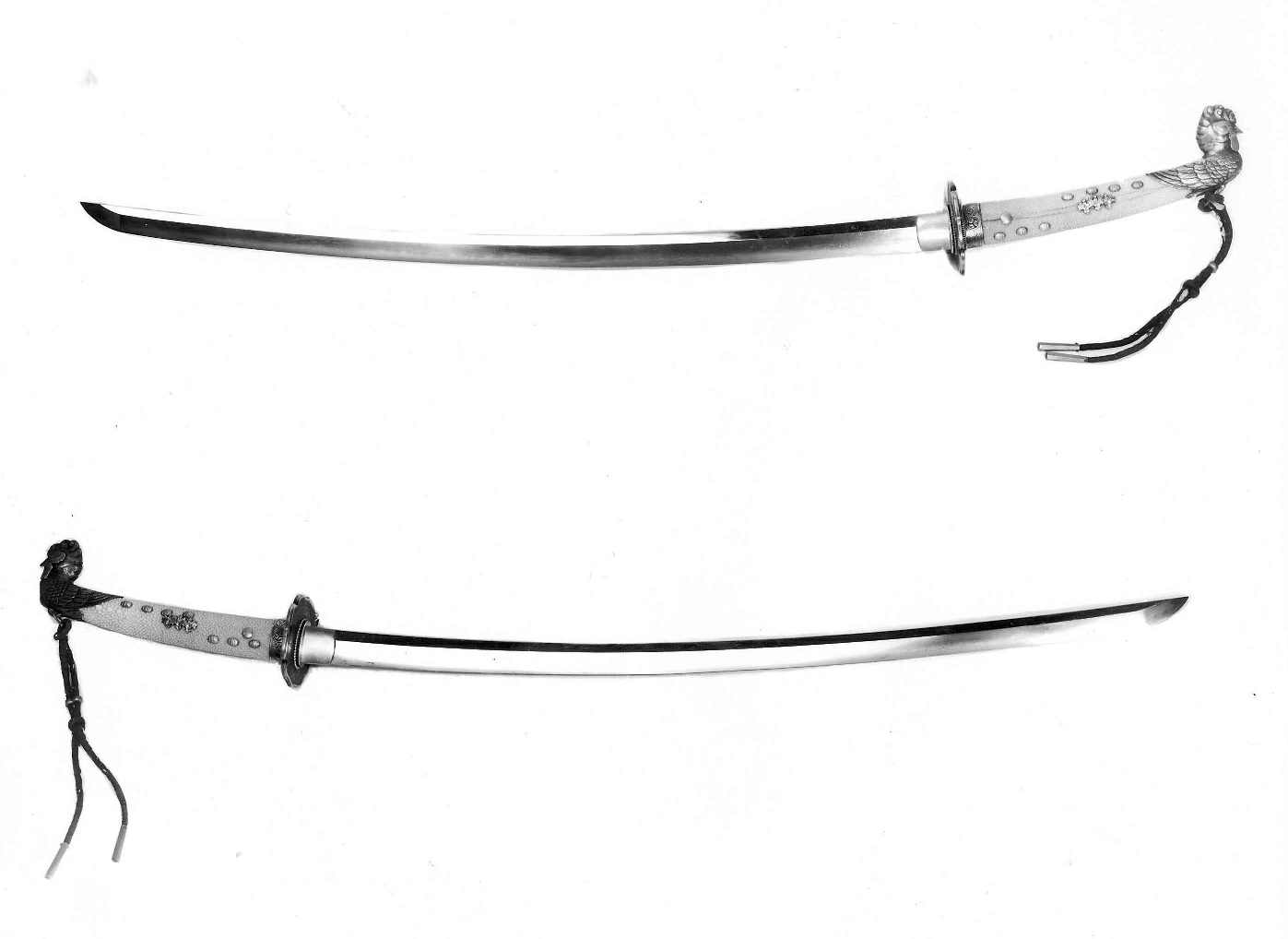

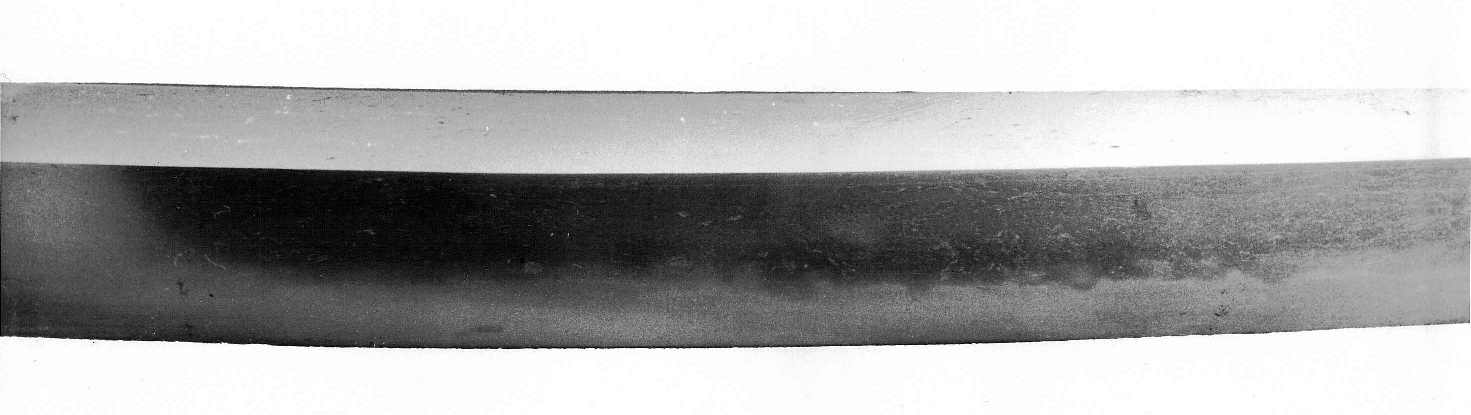

The above listings are mostly of U.S. collections. A listing of European collections of importance would be of great interest - but not in the time we have. But what of individual blades? Well, when then Crown Prince Hirohito visited England before his accession to the throne, he presented a solid gold mounted Efu-no-tachi, blade by Sukesada, to then Edward, Prince of Wales. This blade was pursued for many years by a friend of mine who eventually acquired it. I believe it is still in the United States. On 18 July, 1917, a Japanese artist, Mr. J. Yoshida, presented a "600 year old Samurai Sword" to President Wilson - whereabouts unknown. On 23 October, 1917, a "Samurai of Japan, Yasujiro Ishikawa" presented, on behalf of the Mikado, a tachi mounted sword which was then "386 years old." the blade was signed Uda Sanekuni (ca. 1532), has a Green Paper, and is now in my possession. It came in a "birdhead" tachi koshirae.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the four others which Mr. Ishikawa was carrying on to Europe to present to King George of England, President Poincare of France, King Albert of Belgium, and King Victor Emanuel of Italy may be seen on page 597 of Stone's Glossary, under tachi. The blade of that sword (recipient not known) is by Kaneuji. On 4 July, 1918, Viscount Kikujiro Ishii presented a very fine Bizen tachi (which I have seen and which is being carefully preserved) to the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, on behalf of Dr. Toichiro Nakahama. Dr. Nakahama was the son of one "John Mungo" (otherwise Manjiro Nakahama) who was rescued at sea in June of 1841 by Captain Whitfield of Fairhaven, brought home and raised as a son, and finally returned to Japan. There, among other things, he acted as interpreter for Commodore Perry. Thus the sword has come full circle as a sign of esteem and high regard.

Since World War II, many, many (hundreds of thousands) of swords have come out of Japan, because, upon Japan's loss of World War II, the Nippon-To for the second time lost its place as a status symbol. Once again, they were available in large numbers - some legitimately so, others not quite so. Swords collected during and after World War II fall into two major categories. There are the battlefield souvenirs and the post-war acquisitions. There exists a strange and false myth about the battlefield swords. Both American collectors and Japanese experts have propagated the misconception that there were no good swords on the battlefields. Such belief is, among Americans, understandable, until a genuine assessment is made of the quality of blades so obtained. For Japanese to maintain such a position is either self-deception or profound ignorance of their own national character. The position is based upon a presumption that no one would take a valuable sword into combat, for fear it would be lost.

Come now! The Japanese did not expect to lose a war, or even a battle - and what [would be] more appropriated than that the famous sword of a valiant ancestor should have yet one more victory added to its credit. Even I, a gai-jin, would feel that way today. Perhaps this misconception was based upon a statistical evaluation - certainly there were many Showa-To, blades of no value, lost on the battlefield, but this was only because each soldier did not have access to a sword of his ancestors. There were not enough to go around, either because of numbers or high costs, so that Showa-To and arsenal blades were produced in the millions, thereby diluting the percentage of good blades. It is also true, for the same reasons, that the proportion of good "battlefield" swords was higher in the early phases than toward the end - but the original premise was patently false.

After the war, the Occupation Forces required all swords to be turned in, with the stated goal of destroying them as weapons. Only the ceaseless efforts of Dr. Junji Homma and a few of his associates, and the help of Americans like Colonel Cadwell made it possible to conserve these tangible evidences of a long and rich culture. Nevertheless, the blades were turned in and many blades of great historical and artistic value were lost. Dr. Walter Compton found one of these in the United States - a Koku-Ho Kunimune - and returned it to its owners. Others of lesser importance were returned to specific owners - I was fortunate enough to return a Nagamitsu, dated 1288, to Lieutenant General Nemoto Hiroshi. These blades were returned in realization of their genuine importance to their owners. Hundreds of thousands of others, however, were either given out of the warehouses as souvenirs, "creamed off" from the warehouses by individuals with access and skilled advice from a Japanese assistant, or just plain stolen. I have seen groups of 10-15-30 swords which were "acquired," with no real appreciation of their importance - but with an absolute refusal to release them to individuals who did know and care. I have seen fine swords released to children for chopping brush - a beautiful Soshu tanto employed for 30 years as "the turkey knife." I have seen opportunists grab up every blade in sight to hoard as a "speculation." But then I have also seen individuals and groups undertake a genuine study, first of swords, and then of the entire history and culture of Japan. All of this is necessary if one is really to understand the impact of the Japanese sword or Japanese culture and vice versa. So there are accumulators (they could just as easily collect beer cans), collectors, and students. Then there are American dealers, European dealers, and Japanese dealers. It is very unlikely that any one person is purely one of the above, so we will consider the major thrust of each person's interest. It is my guess that there may be 20-30 genuine students in this country. There are perhaps 3-400 serious collectors, and 7-800 more genuinely interested collectors - and then there are the others.

Early in the occupation phase in Japan, some truly interested gai-jin sought help from a knowledgeable sword expert in Japan. I know that one of these gai-jin was Hans Conried - I don't know any of the others. The expert was Inami Hakusui, proprietor of Japan Sword in Tokyo. He and his son, Tomihiko - I hope both are well - still operate there. Inami wrote, with the encouragement of his class, the book Nippon To. Those of us who have an autographed first edition feel rather fortunate. Then John Yumoto wrote The Samurai Sword, which was my first introduction to this fascinating field. In this country, around 1962, the Japanese Sword Society of the United States was formed. At a later date, I had the honor of twice being Chairman of the J.S.S.U.S. Due to certain differences of opinion, the Southern California Sword Club (Nanka Token Kai) was formed and I was also fortunate to be President of that club at one time. One of the original founders of both of these was Willis Hawley, who has helped maintain momentum through the years. There are other groups which are active and progressive - the group here in the San Francisco area which was formed by John Yumoto - and which we have to thank in great part for this effort. In Chicago, a group formed around Frank Miyamoto; in New York, Bumpei Usui has an active group. Tom Buttweiler organized what was probably the first two national sword shows in the United States in 1967-68. Stanley Kellert has kept the show of the Maryland Sword Society going in Pikesville for many years - and of course Keith Evans, Randy Caldwell, Mike Quigley, and the Dallas group organized and carried off the first ever N.B.T.H.K. Shinsa outside of Japan (the Token KenKyu Kai) to a complete success. With Dr. Kangau Sato as the head of the team, we gai-jin had an opportunity few of us had ever dreamed of. This was followed by the second N.B.T.H.K. Shinsa in Newport Beach, California, and now by the meeting here.

Above and beyond these group efforts have been the almost unbelievable assistance rendered to us individually. I personally had the great privilege of being instructed over a period of years by Fujimura Kunitoshi, a swordsmith of Iwakuni, and an honored friend. It was he who prepared me for the sword-forging set in the Meibutsu Room, to be used just as it is - a study set for those wishing to learn. I have had the good fortune to know Mr. Junyo Sato, who is an advanced Japanese collector and who, over the years, has acted as host and escort. I have been privileged to visit with Mr. Yoshikawa in Japan - and to assist him on a visit to the United States and to read Albert Yamanaka's newsletter, as well as visit with him after he returned to Japan. But above all, I have had the unparalleled opportunity - as has Tom Buttweiler and others - to correspond with, to be advised by, and to receive instruction from Dr. Junji Homma. That has been for years the peak of my pleasure and satisfaction in studying and collecting Japanese swords. It was through his encouragement that I started a short course in Oriental Culture and Its Related Arts at my university in Louisiana (Northeast Louisiana University, in Monroe) - as Tom Buttweiler has done at the Miknihon Art Center in Minneapolis.

|

|

With the constant help, understanding, and instruction of Dr. Homma and others, I think we have now begun to dispel the idea that there are no good swords in the United States (there are several collectors who have one or more Juyo Token - Dr. Compton had sixteen such in one year's Juyo Shinsa), since there are demonstrably first class blades here and many more of Juyo and Bunka-Sai quality yet to be found - as well as certainly a dozen or more Koku-Ho quality blades, either known already or to be found. The second false idea is that there are no gai-jin capable of recognizing or appreciating Nippon-To. If there were none, those good swords just mentioned would still be in use as brush-cutters and cane-cutters. With this beginning, there should now be a sound basis for communication between Japanese and non-Japanese lovers of Japanese swords and arms.

There is more - so much more, such as "how do you explain the painting of the interior of a genuine Oglala Sioux teepee, by the famous Western painter George Catlin, which shows a Japanese war tachi hanging against the inside wall?" and "when will we exhaust our sources of Japanese blades? - and what will collectors do then?" and more. I commend all of those unanswered questions to you - and I thank you for the opportunity to put in my few (hundred) words.

Perhaps the added bibliography may be of some assistance to you. Try it - you'll like it.

Anderson, L. L., Japanese Armour. Harrisberg, 1968.

Arai, Hakuseki, The Armour Book in Honcho Gun-Kiko. London, 1964.

Arms and Armor of Ancient Japan, Southern California token Kai. Los Angeles, 1964.

Ball, Katherine M., Decorative Motives of Oriental Art. London, 1927.

Barboutou, P., Biographic des Artistes Japonais dont les oeuvres Figurent dans la Collection Pierre Barboutou, II. Paris, 1904.

Batchelor, Rev. John, The Ainu of Japan. New York.

Bert, M., Catalogue Vente Drouot. Paris, 1914.

Beurdeley, M., Leduc, M. G., and Sambon, M., Tsuba Exquisite Flower of The Sabre Realities #58, September, 1955. Paris, 1955.

Bing, S., Japon -Artistique, Volume I-III. 1888.

Bjork, Oscar, Auction Catalogue. London, 1920.

Bleed, Peter, "The Japanese Sword in Prehistory," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Bonnet, Hans, Die Waffen der Volker des Alten Orientas. Leipzig, 1926.

The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Bowes, James Lord, Japanese Marks and Seals. London, 1882.

Bowes, James Lord, Notes on Shippo. London, 1895.

Boxer, C. R., "European Influence on Japanese Sword Fittings, 1543-1853," Japanese Society Trans., Vol. XXIII.

Brinkley, Captain F., Japan Its History Arts and Literature. Volume VII. London, 1903-1904.

Brinkley, Captain F., A History of the Japanese People. The Encyclopedia Britannica Co., New York, 1915.

Brinckmann, The Alfred Beit Collection.

Brinckmann, S., Die Sammlung Japanischer Schwertzierathan im Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe zu Hamburg. Hamburg, 1893.

Bullock, Randolph, "Oriental Arms and Armor," Bull. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Series, Vol. V.

Buttweiler, Thomas B., "Seeds of the Bizen Tradition," The Book of the Sword. Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Caldwell, Randolph B., "Rice Gold and the Sword," The Book of the Sword. Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Arms and Armor of Old Japan. The Japan Society of London. London, 1905.

Chamberlain, Professor Basil Hall, Things Japanese and others, Late 19th century, London.

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Japanese Sword Guards, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1921.

Chikashige, M., Alchemy and Other Chemical Achievements of the Orient. Tokyo, 1936.

Christie, Manson and Woods, Various Auction Catalogues. London, 1766-1976.

Collin, Raphael, Vente Drouot. Paris, 1922.

Compton, Walter Ames, "The Shape of Things," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Conder, Josiah, The History of Japanese Costume, Vol. II Armour. Trans Asiatic Society of Japan, 1881.

Cooper, Michael (Translator), This Island of Japan, Joao Rodriguez Account of 16th Century Japan. Rome, 1633. New York, 1973.

Corbin, P., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1920.

Daalen, J. Van, Jr., Auction Catalogue of the Collection of General S. C. Pabst. The Hague, 1956.

Dale, Bon G., Samurai Blades, The Classic Collector, Vol. I, #4, Vol. II, #1. 1973-74.

Dean, Bashford, Japanese Armor, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1905.

Dobree, Alfred, Japanese Sword Blades. London, 1905.

Egerton of Tatton, Rt. Hon Lord, A Description of Indian and Oriental Armour. London, 1896.

Evans, Keith R., "Let the Buyer Beware," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Fedderson, M., "Uber die Benutzung Graphischer Vorbilder fur die Figurelichen Darstellungen auf Japanischen Schwertzieraten." Jarbuch der asiatischen Kunst. 1925.

Franck, G., Altjapanische Kunst Sammlung Oeder aur der Dusseldorfer Ausstellung. Rheinlande, 1902.

Frenzel, K. A., "On Investing in Japanese Swords," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Furnas, Wendell J., "Fortunes in Souvenir Swords," Esquire, November, 1946, Vol. XXVI, No. 5.

Garbutt, Matt, Auction Catalogue. London, 1920.

Garbutt, Matt, "Japanese Armour From the Inside," Trans. of the Japan Society of London, Vol. XI. London, 1914.

Gaskell, S. B., Auction Catalogue. London, 1920.

Gilbertson, E., "The Genealogy of the Miochin," Trans. Japanese Society of London. London, 1892.

Gilbertson, Edward, "Decoration of Swords and Sword Furniture," Trans. Japanese Society of London. London, 1894.

Gilbertson, Edward, "Japanese Chasing and Chasers," The Studio, Vol 7, #35. London, 1896.

Gilbertson, Edward, "Japanese Archery and Archers," Trans. Japanese Society of London. London, 1897.

Gilbertson, Edward G., Auction Catalogue. London, 1917.

Gillot, Charles, Objects d'art et peinture d'Extreme Orient. Paris, 1904.

Gonse, L., Catalogue de l'exposition retrospective de l'art japonais. Paris, 1883.

Gonse, L., L'art japonai. Paris, 1886.

Gonse, Louis, Louis Gonse Collection. Paris, 1924.

Gowland, William, "Metal and Metal Working in Old Japan," Trans. Japanese Society of London. London, 1914-1915.

Grancsay, Stephen V., "The Oriental Armor Gallery," Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, XV. New York, 1920.

Grancsay, S. V., "The Drummond Loan Collection of Sword Furniture," Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, XXIII. New York, 1928.

Grancsay, Stephen V., "A Loan Collection of Oriental Armor," Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, XXIII. New York, 1928.

Grancsay, S. V., "Japanese Metalworks, No Masks and Textiles in the Howard Mansfield Collection," Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, XXXII. New York, 1937.

Greey, Edward, The Bear Worshipers of Yedo. Boston, 1884.

Gunsaulus, Helen C., Japanese Sword Mounts in the Collections of the Field Museum. Chicago, 1923.

Gunsaulus, H. C., "The Japanese Sword and Its Decoration," Field Museum of National History, Department of Anthropology, #20. Chicago, 1924.

Hakusui, Inami, Nippon To. Tokyo, 1948.

Halberstadts, Hugo, Om de japanske Parerplader fra Provinsen Higo. Kololintz, 1929.

Halberstadts, Hugo, Japanske Svaerdprydelser. Copenhagen, 1953.

Hamilton, John D., The Peabody Museum Collection of Japanese Sword Guards. Salem, 1975.

Hancock, Richard, Catalogue of Tsuba in the Permanent Collection of the City of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. No date.

Hara, Shinkichi, Die Meister der Japanischen Schwertzeirathan. Hamburg, 1902.

Hartley, Dean S., Jr., "The Sword Appraisal System," Talk #11, Lecture Series of Japanese Sword Club of Southern California. 1965.

Hartley, Dean S., Jr., "The Sword Appraisal System," The Journal of To-Ken Society of Great Britain, Vol. I, No. 2.

Hartley, Dean S., Jr., "The Shape of the Sword," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Hartley, Dean S., Jr., Oriental Art Objects Exhibit, Catalogue of the Masur Museum of Art, Louisiana, March, 1973.

Hawley, W. M., Oriental Culture Chart #11 Japanese Swords. Hollywood, 1945.

Hawley, Willis M. (Editor), Kizu Yasu Author Japanese Swordsmiths, Vol. 3. Hollywood, 1966.

Hawley, W. M., Tsubas in Southern California. Hollywood, 1968.

Hayashi, T., Catalogue de la Collection des Gardes de Sabre japonaises an Musee de Louvre. Paris, 1894.

Hayashi, Tadamasa, Catalogue de la Collection Dadamasa Hayashi. Paris, 1902-1903.

Histoire de l'art du Japon. Commission Imperale du Japon a l'exposition universelle de Paris. Paris, 1900.

Homma, Junji, Japanese Sword, Japanese Art Series. Tokyo, 1948.

Homma, Junji, Masterpieces of Japanese Swordguards. Tokyo, 1952.

Homma, J., Master Works of Japanese Swords by Masamune and His School. Tokyo, 1961.

Homma, Junji, "An Outline of Japanese Sword Guards," The Book of the Sword, Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Homma, Junji, et al., The Walter A Compton Collection Catalogue. Tokyo, 1976.

Hoopes, Thomas T., Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Japanese Swords and Sword Blades. The Arms and Armor Club, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1923.

Hoopes, Thomas T., "A Recent Acquisition of Japanese Arms and Armor," Metropolitan Museum Studies, Volume II. New York, 1929-1930.

Hoopes, Thomas T., Arms and Armor - An Elementary Guide to the Collection in the City Art Museum of St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A. St. Louis, 1954.

Huish, Marcus B., The Influence of Europe on the Art of Old Japan. Japanese Society of London. London, 1893.

Huish, Marcus B., Japan and Its Art. London, 1912.

Huish, Marcus B., and Holme, C., Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Arms and Armour of Old Japan. The Japanese Society of London. London, 1905.

Jacoby, Gustav, Japanische Schwertzieraten. Berlin, 1904.

Jacoby, Gustav, Schwertzieraten des Provinz Aigo. 1905.

Jacoby, Gustav, Die Schwertzieraten in Ausstellung japonischer Kleinkunst Sammlung Gustav Jacoby. Berlin, 1911.

Japanese Kodzuke and Kogai. An Illustrated Descriptive Catalogue of the Hawkshaw Collection. London, 1911.

The Japanese Sword and Its Fittings. Japanese Sword Society of New York, The Cooper Union Museum. New York, 1966.

Japanese Sword Society of the United States, Inc., Bulletins. San Francisco, St. Louis, 1962 -

Japanese Sword Society of the United States, Inc., Newsletters (Monthly). San Francisco, St. Louis, 1962 -

Japanische Netsuke and Schwertzierant aus Rheinischem Privat Besitz. Cologne, 1922.

Jisl, L., "Japanese Sword Fittings," New Orient Bi-Monthly, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1960.

Jisl, Lumir, Swords of the Samurai. Prague, 1967.

Joly, Henri L., Introduction a l'Etude des Montures de Sabre Japonais. Paris, no date (1905-1910).

Joly, Henri L., Japanese Sword Mounts; Hawkshaw Collection. London, 1910.

Joly, Henri L., Catalogue of the Japanese Collection of H. Seymour Trower. London, 1912.

Joly, Henri L., Japanese Sword Fittings; Naunton Collection. London, 1912.

Joly, Henri L., Note sur le Manuscrit Toban Shinpin Zukan. Paris, 1912.

Joly, Henri L., The W. C. Behrens Collection - 4 Volumes. London, 1913-1915.

Joly, Henri L., Note sur lee fer et le style Namban. Paris, 1914.

Joly, Henri L., "Inscriptions on Japanese Sword Fittings," Transactions and Proceedings of the Japanese Society of London, XV. London, 1917.

Joly, Henri L., The Legend in Japanese Art. London, 1918.

Joly, Henri L., List of Names Kakihan. London, 1919.

Joly, Henri L., Catalogue of a Fine Collection of Tsuba. London, 1921.

Joly, Henri L. and Inada, Hogitara, The Sword and Same. London, 1913.

Joly, Henri L. and Kumasaka, Tomita, Japanese Art and Handicraft (Red Cross Exhibition). London, 1916.

Kizu, Yasu and Hawley W. M. (Editor and Publisher), Japanese Swordsmiths - 3 Volumes. Hollywood, 1966.

Knutzen, Ronald M., Japanese Polearms. London, 1963.

Koop, Albert J., "The Use of Leather in Japanese Military Equipment, Transactions of the Japanese Society of London, Volume XIV. London, 1915-1916.

Koop, Albert J. and Inada, Hogitaro, Japanese Names and How to Read Them. London, 1923.

Krohn, Pietro, Japanske Svaerdprydelser i Det Danske Kunstindustrimuseum. I Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri. 1893.

Kummel, Otto, Kunstgewerbe in Japan. Berlin, 1911.

Kuznitsky, Martin, "Han and KaKihan," Artibus Asiae, Volume IV, No. 1 and 2.

Kuznitsky, Martin, "Han and KaKihan," Ostasiatische Zeitschrift. New Folic, Vol. V, No 9. Berlin, 1933.

Kuznitsky, Martin, "Sammlung von Kunst lersiegel der Meister," Artibus Asiae, Vol. IV. 1913-1937.

LaKing, Sir Guy Francis, Oriental Arms and Armour in the Wallace Collection. London, 1914.

Luhr, Hermann, Uber japonische Stichblatter. Heidelberg, 1897.

Lyman, Benjamin S., Japanese Swords. Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, 1890.

Lyman, Benjamin S., "Japanese Swords," Journal of the Franklin Institute. Philadelphia, 1895.

Lyman, Benjamin Smith, "Metallurgical and Other Features of Japanese Swords," Journal of the Franklin Institute. Philadelphia, 1896.

Manos, M., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1913.

Mansfield, Howard, Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Japanese Sword Fittings Held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1922.

McClatchie, Thomas R. H., "The Sword of Japan," Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. 1873-1874.

Mene, Dr., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1913.

Migeon, Chefs d'oeuvre d'Art Japonais. Paris, 1905.

Miller, Benjamin N., Captain, "Collecting Japanese Weapons," The Gun Report, Vol V, No 7, 1959.

Millot, Jacques, Auction Catalogue. Paris, 1931.

Modderman, E. S., "Het Japansche Zwaard," Bulletin Van de Ver, Voor Japanesche Grafieken Kleinkunst, Volume I, No. 8, Januar. Berlin, 1941.

Moser, Henri, Collections of Henri Moser - Charlottenfels Oriental Arms and Armour. Leipzig, 1912.

Mosle, Alexander G., Ausstellung Sammlung Mosle. 1909.

Mosle, Alexander G., "The Sword - Ornaments of the Goto Shiroebi Family." Transactions of the Japanese Society of London, Vol. VII. London.

Meunsterberg, Oskar, Japanische Kunstgeschichte. Braunschweig, 1907.

Mumford, Ethel Watts, "The Japanese Book of the Ancient Sword," Journal of the American Oriental Society. New York, 1905.

Nesselrode, Armes and Armures de la Collection du Comete de Nesselrode au Chateau de Tzareutchina. Paris, 1904.

Newman, Alex R., "Japanese Sword Guards or Tsubas," Apollo Vol. XLIII, No 225, May 1946. London, 1946.

Oeder, George, Japanische Stichblatter und Schwertzieraten. Berlin - no date.

Ogasawara, Nobuo, Japanese Swords. Tokyo, 1970.

Ogawa, K., Military Custume in Old Japan. No city - no date.

Okabe, KiKuya, Japanese Sword Guards. Boston, 1908.

Ostasiatisches, Kunstgewerbe aus den chemalizen Besitze des Prinzen Henrich V. Bourbon. Vienna, 1922.

Polo, Marco, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, Edited by Sir Henry Yule. London, 1926.

Poncetton, Francois, Les Gardes de Sabre Japonaise. Paris, 1924.

Poncetton, Fr., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1929.

Raphael, Pumpelly, "Notes on Japanese Alloys," American Journal of Science, Vol. 42, 1866.

Robinson, B. Arms and Armour of Old Japan. London, 1951.

Robinson, B. W., A Primer of Japanese Sword Blades. Surrey, 1955.

Robinson, B. W., The Arts of the Japanese Sword. London, 1961.

Robinson, H. Russell, "A Plea for Japanese Armour," Apollo, March, 1950.

Robinson, H. Russell, "Yoroi The Armour of Japan," Bulletin of the Japanese Society of London, No. 9, London, 1951.

Robinson, H. Russell, "Kabuto Japanese Helmets," Journal of the Arms and Armour Society of London, Vol. I, No. 1. London, 1953.

Robinson, H. Russell, "Namban Gusoku," Journal of the Arms and Armour Society of London, Vol. I, No. 7, London, 1954.

Robinson, H. Russell, "Japanese Armour," The Concise Encyclopedia of Antiques, Vol. V, London, 1961.

Robinson, H. Russell, A Short History of Japanese Armour. London, 1965.

Robinson, H. Russell, Oriental Armour. New York, 1967.

Rouart, A., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1911.

Roubeaud, A., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1920.

Rucker, Robert H., Catalogue of the Goda Collection. Metropolitan Museum of New York. New York, 1924.

Sakakibara, Kozan, The Manufacture of Armour and Helmets in 16th. Century Japan. London, 1963.

Sansano, Masayuki, Early Japanese Sword Guards. Tokyo, 1972.

Scidmore, Eliza Rhuama, "The Japanese Yano-Ne," Transactions of the Japanese Society of London. London, 1904.

Smith, Cyril Stanley, "A Metallographic Examination of Some Japanese Sword Blades," Doc e contributi per la storia della metallurgia, No 2. Milan, 1957.

Smith, Cyril Stanley, A History of Metallography. Chicago, 1960.

Sotheby, Parke Bernet, Various Auction Catalogues. London-New York.

Stone, G. C., A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armour. Portland, 1934.

Strohl, Hugo Gerard, Japanisches Wappenbuch. Vienna, 1906.

Suzuki, Tanto. Translated by Japanese Sword Society of U.S.A., Inc. St. Louis, 1973.

Token Kai, Willis Hawley, Secretary, Various publications, bulletins, pamphlets, etc. Monthly newsletter. Hollywood, 1963.

Token Society of Great Britain, Monthly Bulletin. London, 1964.

Token Society of Great Britain, The Journals of the Token Society of Great Britain. London, 1965.

Token Society of Great Britain, Token Catalogue. London, 1968.

Tomita, K. and Inada, H., Pedigrees of Japanese Metalworkers in Sword Fittings. 1930.

Tomkinson, Michael, Catalogue of the Michael Tomkinson Collection.

Tressan, Marquis de, L'Evolution de la Garde do Sabre Japonaise. Societe Franco-Japonaise. 1910-11-12.

Tressan, Marquis G. de, Tei-San Notes sur l'Art Japonais. Paris, 1906.

Tressan, Marquis G. de, Vente Drouot. Paris, 1933.

Vautier, P., Japonische Stichblatter und Schwertzieraten in der Sammlung Georg Order. Berlin, 1917.

Vautier, P., Japonische Schwertzieraten der Sammlung G. Berlin, 1920.

Vincent, Benjamin, Naginata Fundimentals Token Bijutsu. No. 157. Tokyo, 1957.

Volker, T., "Kozuka," Bulletin van de Ver Voor Japansche Grafiek en Kleinkunst, Vol. 3, No 1. 1955.

Vog, F., "Tsuba," Bulletin van de Ver Voor Japansche Grafiek en Kleinkunst, Vol. 2, No 6-7-8. 1945.

Wallis and Wallis, Various Auction Catalogues. Lewes, 1948-1976.

Wastrall, Charles, Exhibition Catalogue.

Weber, F. V., Ko-Ji Ho-Ten. Paris, 1923.

Weber, F. V., Vente Drouot. Paris, 1975.

Yamagami, Hatiro, Japans Ancient Armour. Tokyo, 1940.

Yamanaka, Albert, Nihonto Newsletter. Monthly. Tokyo, 1968-1972.

Yumoto, John, The Samurai Sword - A Handbook. Rutland, 1958.

Yumoto, John, "Random Thoughts," The Book of the Sword. Token KenKyu Kai. Dallas, 1972.

Yumoto, John, Arami Neizukushi. Translation. San Francisco, 1975.

Yumoto, John, Translation of Tsuba Kanshiro by Torigoye. San Francisco. No date.

Zeller, Rudolf and Rohrer, Ernst F., Orientalische Sammlung Henri Moser-Charlottenfels. Catalogue of the Bernisches Historisches Museum.

Zylinsky, Major, List of Swordsmiths. C. 1900.

Website created by Dean S. Hartley III.